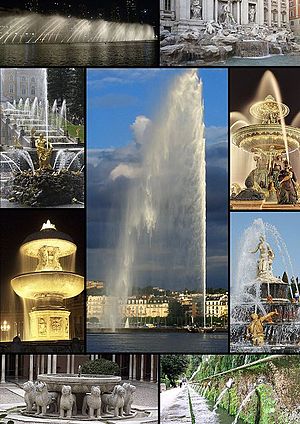

Fountain

The ancient Assyrians constructed a series of basins in the gorge of the Comel River, carved in solid rock, connected by small channels, descending to a stream.

[4] Greek fountains were made of stone or marble, with water flowing through bronze pipes and emerging from the mouth of a sculpted mask that represented the head of a lion or the muzzle of an animal.

[5] The Ancient Romans built an extensive system of aqueducts from mountain rivers and lakes to provide water for the fountains and baths of Rome.

Pliny the Younger described the banquet room of a Roman villa where a fountain began to jet water when visitors sat on a marble seat.

[10] In illuminated manuscripts like the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1411–1416), the Garden of Eden was shown with a graceful gothic fountain in the center (see illustration).

The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck, finished in 1432, also shows a fountain as a feature of the adoration of the mystic lamb, a scene apparently set in Paradise.

Simple fountains, called lavabos, were placed inside Medieval monasteries such as Le Thoronet Abbey in Provence and were used for ritual washing before religious services.

The medieval romance The Roman de la Rose describes a fountain in the center of an enclosed garden, feeding small streams bordered by flowers and fresh herbs.

The Fontana Maggiore in Perugia, dedicated in 1278, is decorated with stone carvings representing prophets and saints, allegories of the arts, labors of the months, the signs of the zodiac, and scenes from Genesis and Roman history.

[15] In the 9th century, the Banū Mūsā brothers, a trio of Persian Inventors, were commissioned by the Caliph of Baghdad to summarize the engineering knowledge of the ancient Greek and Roman world.

The patio of the Sultan in the gardens of Generalife in Granada (1319) featured spouts of water pouring into a basin, with channels which irrigated orange and myrtle trees.

The Shalimar Gardens built by Emperor Shah Jahan in 1641, were said to be ornamented with 410 fountains, which fed into a large basin, canal and marble pools.

The treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria, by Leon Battista Alberti, which described in detail Roman villas, gardens and fountains, became the guidebook for Renaissance builders.

[24] In Rome, Pope Nicholas V (1397–1455), himself a scholar who commissioned hundreds of translations of ancient Greek classics into Latin, decided to embellish the city and make it a worthy capital of the Christian world.

In 1453, he began to rebuild the Acqua Vergine, the ruined Roman aqueduct which had brought clean drinking water to the city from eight miles (13 km) away.

The great Medici Villa at Castello, built for Cosimo by Benedetto Varchi, featured two monumental fountains on its central axis; one showing with two bronze figures representing Hercules slaying Antaeus, symbolizing the victory of Cosimo over his enemies; and a second fountain, in the middle of a circular labyrinth of cypresses, laurel, myrtle and roses, had a bronze statue by Giambologna which showed the goddess Venus wringing her hair.

[30] By the middle Renaissance, fountains had become a form of theater, with cascades and jets of water coming from marble statues of animals and mythological figures.

Salvi compensated for this problem by sinking the fountain down into the ground, and by carefully designing the cascade so that the water churned and tumbled, to add movement and drama.

[38] Wrote historians Maria Ann Conelli and Marilyn Symmes, "On many levels the Trevi altered the appearance, function and intent of fountains and was a watershed for future designs.

The Fontaine Latone (1668–70) designed by André Le Nôtre and sculpted by Gaspard and Balthazar Marsy, represents the story of how the peasants of Lycia tormented Latona and her children, Diana and Apollo, and were punished by being turned into frogs.

This statue shows a theme also depicted in the painted decoration in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles: Apollo in his chariot about to rise from the water, announced by Tritons with seashell trumpets.

Historians Mary Anne Conelli and Marilyn Symmes wrote, "Designed for dramatic effect and to flatter the king, the fountain is oriented so that the Sun God rises from the west and travels east toward the chateau, in contradiction to nature.

The gardens included trick fountains designed to drench unsuspecting visitors, a popular feature of the Italian Renaissance garden.,[42] In 1800–1802 the Emperor Paul I of Russia and his successor, Alexander I of Russia, built a new fountain at the foot of the cascade depicting Samson prying open the mouth of a lion, representing Peter's victory over Sweden in the Great Northern War in 1721.

By the end of the 19th century fountains in big cities were no longer used to supply drinking water, and were simply a form of art and urban decoration.

The Exposition Universelle (1889) which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution featured a fountain illuminated by electric lights shining up though the columns of water.

These fountains are designed to allow easy access, and feature nonslip surfaces, and have no standing water, to eliminate possible drowning hazards, so that no lifeguards or supervision is required.

In some splash fountains, such as Dundas Square in Toronto, Canada, the water is heated by solar energy captured by the special dark-colored granite slabs.

Many jurisdictions require water fountains to be wheelchair accessible (by sticking out horizontally from the wall), and to include an additional unit of a lower height for children and short adults.

[63] The architects of the fountains at Versailles designed specially-shaped nozzles, or tuyaux, to form the water into different shapes, such as fans, bouquets, and umbrellas.

In Germany, some courts and palace gardens were situated in flat areas, thus fountains depending on pumped pressurized water were developed at a fairly early point in history.