Frances Slocum

Slocum was born into a Quaker family that migrated from Warwick, Rhode Island, in 1777 to the Wyoming Valley in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania.

On March 3, 1845, the United States Congress passed the joint resolution that exempted Slocum and twenty-one of her Miami relatives from removal to Kansas Territory.

[2] The Slocum family, who were Quakers and pacifists, emigrated from Warwick, Rhode Island, to the Wyoming Valley in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, in 1777.

Although the Slocum family remained in the settlement, many others fled during the Battle of Wyoming in July 1778,[6] when British forces and Seneca warriors destroyed Forty Fort near Wilkes-Barre, killing more than three hundred American settlers.

Ruth and all but two of her children escaped into the nearby woods, but the Delaware captured five-year-old Frances, her disabled brother, Ebenezer, and Wareham Kingsley, a young boy whose family was living with the Slocums.

[13] She later recalled that they migrated west through Niagara Falls and Detroit, before settling near Kekionga (the site of present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana).

[18] The couple had four children: two sons, who died at a young age, and two daughters, Kekenakushwa (Cut Finger)[19] and Ozahshinquah (Yellow Leaf),[20] who both survived to adulthood.

[2] Sometime after the War of 1812 the Miami tribe, which included She-pan-can-ah and Maconaquah (Slocum), moved to the Mississinewa River valley in north central Indiana.

[24] Ewing believed that Slocum wanted to reveal her identity, a secret she had kept for more than fifty years, because she was in poor health and thought she might die soon.

It was discovered two years later and a notice was published in an extra edition of the Lancaster Intelligencer, where it caught the attention of a minister in the Wyoming Valley.

[27][37] During their visits the Slocum family confirmed that she was their lost sister from the information she provided, and especially after recognizing the disfigured forefinger on her left hand, which was the result of a childhood accident prior to her capture.

In these treaties the Miami ceded all but a small portion of their remaining tribal lands in Indiana to the federal government, and in 1840 they also agreed to move west of the Mississippi River within five years.

[39][40][41] A treaty made in November 1838, three years after Slocum revealed her identity, provided some Miami families with individual land grants that would allow them to remain in Indiana.

This strategy, combined with political maneuvering, helped tribal leaders (namely Miami chief Francis Godfroy) gain enough support to delay the removal process for several years, and in some situations exempting some members of the community from removal to reservation lands west of the Mississippi River.

[47] To gain sympathy from members of Congress, Slocum's lawyer, Alphonzo Cole, of Peru, Indiana, portrayed her as an old woman who had endured years of hardship and captivity and only wished to remain near her family—both white and Indian.

Congressman Benjamin Bidlack of Pennsylvania, who introduced the House resolution was sympathetic to her cause and stressed the importance of Slocum staying close to her white relatives, although she had met only a few of them.

[48][49] On March 3, 1845, Congress passed a joint resolution that exempted Slocum and 21 members of her Miami village from removal to reservation lands in the Kansas Territory.

[45] With congressional approval of her petition, Slocum and the members of her Miami village were able to continue living on their land in Indiana.

[55][56] In antebellum America, when most Americans viewed Indians as uncivilized, the ethnographic content of Winter's drawings "with few exceptions", provided an honest and reliable record of specific aspects of the Miami and Potawatomi culture from one of the few Euro-American artists working in northern Indiana.

The extensive number of his surviving works and his detailed documentation are noted as reliable primary sources for historical studies of the Native American tribes of Indiana's Wabash Valley.

[60] The description of Slocum that Winter wrote in his journal closely fits his original sketch:Though bearing some resemblance to her family (white), yet her cheekbones seemed to have the Indian characteristics—face broad, nose bulby, mouth indicating some degree of severity, her eyes pleasant and kind.

Winter described his presence in the village: "I could but feel as by intuition, that my absence would be hailed as a joyous relief to the family.

In the formal oil portrait for the Slocum family, she is somber, her skin appears lighter, and her clothes are not as vibrant or detailed.

In the other version, which included Slocum and her two daughters, her deeply lined face appears darker skinned and her clothing is more colorful and detailed.

Her daughter Ozahshinquah, who refused to look at Winter's original sketch, appears on the left with her back to the artist, a common native practice.

[2][11] Slocum's story is one of an individual who was forcibly kidnapped and made to fully assimilate into the Native American culture that surrounded her, and was accepted as one of its members.

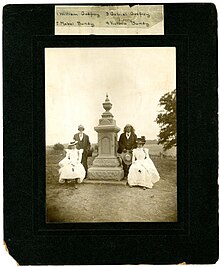

The zinc marker with an extensive epitaph is a tribute to her life as Maconaquah and Frances Slocum, as well as to her second husband, She-pan-can-ah (Deaf Man), who is commemorated on one side of the monument.