Mississippi River

[c][15][16] From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it flows generally south for 2,340 miles (3,766 km)[16] to the Mississippi River Delta in the Gulf of Mexico.

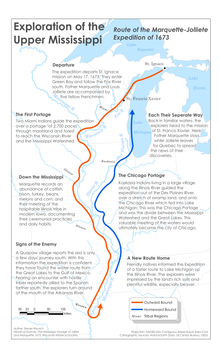

In the 19th century, during the height of the ideology of manifest destiny, the Mississippi and several tributaries, most notably its largest, the Ohio and Missouri, formed pathways for the western expansion of the United States.

Formed from thick layers of the river's silt deposits, the Mississippi embayment, and American Bottom are some of the most fertile regions of the United States; steamboats were widely used in the 19th and early 20th centuries to ship agricultural and industrial goods.

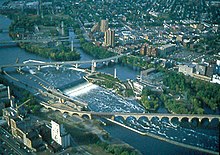

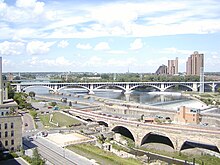

Because of the substantial growth of cities and the larger ships and barges that replaced steamboats, the first decades of the 20th century saw the construction of massive engineering works such as levees, locks and dams, often built in combination.

Since the 20th century, the Mississippi River has also experienced major pollution and environmental problems, most notably elevated nutrient and chemical levels from agricultural runoff, the primary contributor to the Gulf of Mexico dead zone.

Measurements of the length of the Mississippi from Lake Itasca to the Gulf of Mexico vary somewhat, but the United States Geological Survey's number is 2,340 miles (3,766 km).

The Mississippi River water rounded the tip of Florida and traveled up the southeast coast to the latitude of Georgia before finally mixing in so thoroughly with the ocean that it could no longer be detected by MODIS.

The upwelling of magma from the hotspot forced the further uplift to a height of perhaps 2–3 km of part of the Appalachian-Ouachita range, forming an arch that blocked southbound water flows.

The uplifted land quickly eroded and, as North America moved away from the hot spot and as the hotspot's activity declined, the crust beneath the embayment region cooled, contracted and subsided to a depth of 2.6 km, and around 80 million years ago the Reelfoot Rift formed a trough that was flooded by the Gulf of Mexico.

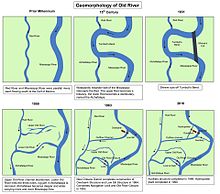

[48][49] Through a natural process known as avulsion or delta switching, the lower Mississippi River has shifted its final course to the mouth of the Gulf of Mexico every thousand years or so.

This occurs because the deposits of silt and sediment begin to clog its channel, raising the river's level and causing it to eventually find a steeper, more direct route to the Gulf of Mexico.

When the ice sheet began to recede, hundreds of feet of rich sediment were deposited, creating the flat and fertile landscape of the Mississippi Valley.

A major flood in 1881 caused it to overtake the lower 10 miles (16 km) of the Kaskaskia River, forming a new Mississippi channel and cutting off the town from the rest of the state.

Four great earthquakes in 1811 and 1812, estimated at 8 on the Richter magnitude scale, had tremendous local effects in the then sparsely settled area, and were felt in many other places in the Midwestern and eastern U.S.

The second canal, in addition to shipping, also allowed Chicago to address specific health issues (typhoid fever, cholera and other waterborne diseases) by sending its waste down the Illinois and Mississippi river systems rather than polluting its water source of Lake Michigan.

The Corps of Engineers recommended the excavation of a 5-foot-deep (1.5 m) channel at the Des Moines Rapids, but work did not begin until after Lieutenant Robert E. Lee endorsed the project in 1837.

27), which consists of a low-water dam and an 8.4-mile-long (13.5 km) canal, was added in 1953, just below the confluence with the Missouri River, primarily to bypass a series of rock ledges at St. Louis.

The Corps now actively creates and maintains spillways and floodways to divert periodic water surges into backwater channels and lakes, as well as route part of the Mississippi's flow into the Atchafalaya Basin and from there to the Gulf of Mexico, bypassing Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

[77] Some of the pre-1927 strategy remains in use today, with the Corps actively cutting the necks of horseshoe bends, allowing the water to move faster and reducing flood heights.

[78] Approximately 50,000 years ago, the Central United States was covered by an inland sea, which was drained by the Mississippi and its tributaries into the Gulf of Mexico—creating large floodplains and extending the continent further to the south in the process.

[79] The area of the Mississippi River basin was first settled by hunting and gathering Native American peoples and is considered one of the few independent centers of plant domestication in human history.

A network of trade routes referred to as the Hopewell interaction sphere was active along the waterways between about 200 and 500 AD, spreading common cultural practices over the entire area between the Gulf of Mexico and the Great Lakes.

After around 800 AD there arose an advanced agricultural society today referred to as the Mississippian culture, with evidence of highly stratified complex chiefdoms and large population centers.

[82][83][84] Modern American Indian nations inhabiting the Mississippi basin include Cheyenne, Sioux, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Fox, Kickapoo, Tamaroa, Moingwena, Quapaw and Chickasaw.

Due to ongoing U.S. colonization creating facts on the ground, and U.S. military actions, Spain ceded both West and East Florida in their entirety to the United States in the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

The last serious European challenge to U.S. control of the river came at the conclusion of the War of 1812, when British forces mounted an attack on New Orleans just 15 days after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent.

The Nature Conservancy's project called "America's Rivershed Initiative" announced a 'report card' assessment of the entire basin in October 2015 and gave the grade of D+.

[113] While the risk of such a diversion is present during any major flood event, such a change has so far been prevented by active human intervention involving the construction, maintenance, and operation of various levees, spillways, and other control structures by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

These additional facilities give the Corps much more flexibility and potential flow capacity than they had in 1973, which further reduces the risk of a catastrophic failure in this area during other major floods, such as that of 2011.

[131] The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has designated much of the Mississippi River in the state as infested waters by the exotic species zebra mussels and Eurasian watermilfoil.

In late 2022 there was low river levels that caused two backups on the Lower Mississippi River that held up over 100 tow boats with 2,000 barge units and caused barge rates to soar [ 65 ] [ 66 ]