Franks Casket

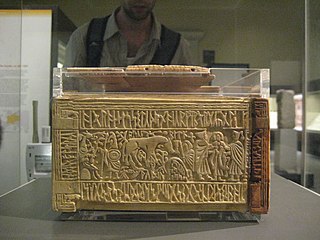

A monastic origin is generally accepted for the casket, which was perhaps made for presentation to an important secular figure, and Wilfrid's foundation at Ripon has been specifically suggested.

The missing right end panel was later found in a drawer by the family in Auzon and sold to the Bargello Museum, Florence, where it was identified as part of the casket in 1890.

[11] Leslie Webster regards the casket as probably originating in a monastic context, where the maker "clearly possessed great learning and ingenuity, to construct an object which is so visually and intellectually complex.

... it is generally accepted that the scenes, drawn from contrasting traditions, were carefully chosen to counterpoint one another in the creation of an overarching set of Christian messages.

What used to be seen as an eccentric, almost random, assemblage of pagan Germanic and Christian stories is now understood as a sophisticated programme perfectly in accord with the Church's concept of universal history".

Wayland (also spelled Weyland, Welund or Vølund) stands at the extreme left in the forge where he is held as a slave by King Niðhad, who has had his hamstrings cut to hobble him.

[13] In a sharp contrast, the right-hand scene shows one of the most common Christian subjects depicted in the art of the period; however here "the birth of a hero also makes good sin and suffering".

Richard Fletcher considered this contrast of scenes, from left to right, as intended to indicate the positive and benign effects of conversion to Christianity.

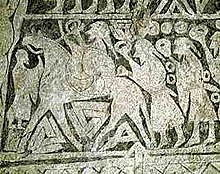

[16]The left panel depicts the mythological twin founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, being suckled by a she-wolf lying on her back at the bottom of the scene.

The inscription reads: Carol Neuman de Vegvar (1999) observes that other depictions of Romulus and Remus are found in East Anglian art and coinage (for example the very early Undley bracteate).

The associated text reads 'ᚻᛖᚱᚠᛖᚷᛏᚪᚦ | ᛭ᛏᛁᛏᚢᛋᛖᚾᛞᚷᛁᚢᚦᛖᚪᛋᚢ' (in Latin transliteration herfegtaþ | +titusendgiuþeasu, and if normalised to Late West Saxon 'Hēr feohtaþ Tītus and Iūdēas'): 'Here Titus and the Jews fight'.

In the lower left quadrant, a seated judge announces the judgement of the defeated Jews, which as recounted in Josephus was to be sold into slavery.

[21] The lid shows a scene of an archer, labelled ᚫᚷᛁᛚᛁ or Ægili, single-handedly defending a fortress against a troop of attackers, who from their larger size may be giants.

The Pforzen buckle inscription, dating to about the same period as the casket, also makes reference to the couple Egil and Olrun (Áigil andi Áilrun).

The British Museum webpage and Leslie Webster concur, the former stating that "The lid appears to depict an episode relating to the Germanic hero Egil and has the single label ægili = 'Egil'.

"[24] Leopold Peeters (1996:44) proposes that the lid depicts the defeat of Agila, the Arian Visigothic ruler of Hispania and Septimania, by Roman Catholic forces in 554 A.D.

"[25] Webster (2012b:46-8) notes that the two-headed beast both above and below the figure in the room behind the archer also appears beneath the feet of Christ as King David in an illustration from an 8th-century Northumbrian manuscript of Cassiodorus, Commentary on the Psalms.

rixe / wudu / bita She suffers distress as Ertae had imposed it upon her, a wretched den (?wood) of sorrows and of torments of mind.

Elis Wadstein (1900) proposed that the right panel depicts the Germanic legend of Sigurd, known also as Siegfried, being mourned by his horse Grani and wife Guthrun.

Eleanor Clark (1930) added, "Indeed, no one seeing the figure of the horse bending over the tomb of a man could fail to recall the words of the Guthrunarkvitha (II,5): While Clark admits that this is an "extremely obscure legend,"[31] she assumes that the scene must be based on a Germanic legend, and can find no other instance in the entire Norse mythology of a horse weeping over a dead body.

[32] She concludes that the small, legless person inside the central mound must be Sigurd himself, with his legs gnawed off by the wolves mentioned in Guthrun's story.

The gateway to these glittering fields is guarded by a winged dragon who feeds on the imperishable flora that characterised the place, and the bodyless cock crows lustily as a kind of eerie genius loci identifying the spot as Hel's wall.

The miniature person inside the burial mound he grieves over would then be Horsa, who died at the battle of Ægelesthrep in 455 A.D. and was buried in a flint tumulus at Horsted near Aylesford.

Alfred Becker (1973, 2002), following Krause, interprets herh as a sacred grove, the site where in pagan days the Æsir were worshipped, and os as a goddess or valkyrie.

David Howlett (1997) identifies the illustrations on the right panel with the story of the death of Balder, as told by the late 12th-century Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum.

As a penance, she was required, as depicted in the scene on the left, "to sit beside the horse-block outside the gates of the court for seven years, offering to carry visitors up to the palace on her back, like a beast of burden.... Rhiannon's horse-imagery and her bounty have led scholars to equate her with the Celtic horse-goddess Epona.

"[42] Austin Simmons (2010) parses the frame inscription into the following segments: This he translates, "The idol sits far off on the dire hill, suffers abasement in sorrow and heart-rage as the den of pain had ordained for it."

“In this box our warrior hoarded his treasure, golden rings and bands and bracelets, jewellery he had received from his lord, … which he passed to his own retainers… This is feohgift, a gift not only for the keep of this or that follower, but also to honour him in front of his comrade-in-arms in the hall.”[45] The Romulus and Remus inscription alliterates on the R-rune ᚱ rad (journey or ride), evoking both how far from home the twins had journeyed and the owner's call to arms.

The right side alliterates first on the H-rune ᚻ hagal (hail storm or misfortune) and then on the S-rune ᛋ sigel (sun, light, life), and illustrates the hero's death and ultimate salvation, according to Becker.

"In order to reach certain values the carver had to choose quite unusual word forms and ways of spelling which have kept generations of scholars busy.