Late antiquity

[4] It was given currency in English partly by the writings of Peter Brown, whose survey The World of Late Antiquity (1971) revised the Gibbon view of a stale and ossified Classical culture, in favour of a vibrant time of renewals and beginnings, and whose The Making of Late Antiquity offered a new paradigm of understanding the changes in Western culture of the time in order to confront Sir Richard Southern's The Making of the Middle Ages.

While the usage "Late Antiquity" suggests that the social and cultural priorities of classical antiquity endured throughout Europe into the Middle Ages, the usage of "Early Middle Ages" or "Early Byzantine" emphasizes a break with the classical past, and the term "Migration Period" tends to de-emphasize the disruptions in the former Western Roman Empire caused by the creation of Germanic kingdoms within her borders beginning with the foedus with the Goths in Aquitania in 418.

As a result of this decline, and the relative scarcity of historical records from Europe in particular, the period from roughly the early fifth century until the Carolingian Renaissance (or later still) was referred to as the "Dark Ages".

The 4th century Christianization of the Roman Empire was extended by the conversions of Tiridates the Great of Armenia, Mirian III of Iberia, and Ezana of Axum, who later invaded and ended the Kingdom of Kush.

The campaigns of Justinian the Great led to the fall of the Ostrogothic and Vandal Kingdoms, and their reincorporation into the Empire, when the city of Rome and much of Italy and North Africa returned to imperial control.

[citation needed] The middle of the 6th century was characterized by extreme climate events (the volcanic winter of 535–536 and the Late Antique Little Ice Age) and a disastrous pandemic (the Plague of Justinian in 541).

[citation needed] One of the most important transformations in late antiquity was the formation and evolution of the Abrahamic religions: Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism and, eventually, Islam.

By the late 4th century, Emperor Theodosius the Great had made Christianity the State religion, thereby transforming the Classical Roman world, which Peter Brown characterized as "rustling with the presence of many divine spirits.

Holy Fools and Stylites counted among the more extreme forms but through such personalities like John Chrysostom, Jerome, Augustine or Gregory the Great monastic attitudes penetrated other areas of Christian life.

[17] Late antiquity marks the decline of Roman state religion, circumscribed in degrees by edicts likely inspired by Christian advisors such as Eusebius to 4th-century emperors, and a period of dynamic religious experimentation and spirituality with many syncretic sects, some formed centuries earlier, such as Gnosticism or Neoplatonism and the Chaldaean oracles, some novel, such as Hermeticism.

Culminating in the reforms advocated by Apollonius of Tyana being adopted by Aurelian and formulated by Flavius Claudius Julianus to create an organized but short-lived pagan state religion that ensured its underground survival into the Byzantine age and beyond.

[18] Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India and along the Silk Road in Central Asia, while Manichaeism, a Dualist faith, arose in Mesopotamia and spread both East and West, for a time contending with Christianity in the Roman Empire.

[19] These men presented themselves as removed from the traditional Roman motivations of public and private life marked by pride, ambition and kinship solidarity, and differing from the married pagan leadership.

Related to this is the Pirenne Thesis, according to which the Arab invasions marked—through conquest and the disruption of Mediterranean trade routes—the cataclysmic end of late antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

[citation needed] The Roman citizen elite in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, under the pressure of taxation and the ruinous cost of presenting spectacular public entertainments in the traditional cursus honorum, had found under the Antonines that security could be obtained only by combining their established roles in the local town with new ones as servants and representatives of a distant emperor and his traveling court.

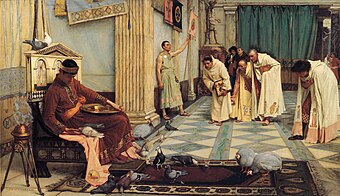

Room at the top of late antique society was more bureaucratic and involved increasingly intricate channels of access to the emperor; the plain toga that had identified all members of the Republican senatorial class was replaced with the silk court vestments and jewelry associated with Byzantine imperial iconography.

[29] The urban continuity of Constantinople is the outstanding example of the Mediterranean world; of the two great cities of lesser rank, Antioch was devastated by the Persian sack of 540, followed by the plague of Justinian (542 onwards) and completed by earthquake, while Alexandria survived its Islamic transformation, to suffer incremental decline in favour of Cairo in the medieval period.

[citation needed] Justinian rebuilt his birthplace in Illyricum, as Justiniana Prima, more in a gesture of imperium than out of an urbanistic necessity; another "city", was reputed to have been founded, according to Procopius' panegyric on Justinian's buildings,[30] precisely at the spot where the general Belisarius touched shore in North Africa: the miraculous spring that gushed forth to give them water and the rural population that straightway abandoned their ploughshares for civilised life within the new walls, lend a certain taste of unreality to the project.

Aside from a mere handful of its continuously inhabited sites, like York and London and possibly Canterbury, however, the rapidity and thoroughness with which its urban life collapsed with the dissolution of centralized bureaucracy calls into question the extent to which Roman Britain had ever become authentically urbanized: "in Roman Britain towns appeared a shade exotic," observes H. R. Loyn, "owing their reason for being more to the military and administrative needs of Rome than to any economic virtue".

[37] Gildas lamented the destruction of the twenty-eight cities of Britain; though not all in his list can be identified with known Roman sites, Loyn finds no reason to doubt the essential truth of his statement.

[37] Classical antiquity can generally be defined as an age of cities; the Greek polis and Roman municipium were locally organised, self-governing bodies of citizens governed by written constitutions.

Due to the stress on civic finances, cities spent money on walls, maintaining baths and markets at the expense of amphitheaters, temples, libraries, porticoes, gymnasia, concert and lecture halls, theaters and other amenities of public life.

[citation needed] City life in the East, though negatively affected by the plague in the 6th–7th centuries, finally collapsed due to Slavic invasions in the Balkans and Persian destructions in Anatolia in the 620s.

Additionally, mirroring the rise of Christianity and the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, painting and freestanding sculpture gradually fell from favor in the artistic community.

Sarcophagi carved in relief had already become highly elaborate, and Christian versions adopted new styles, showing a series of different tightly packed scenes rather than one overall image (usually derived from Greek history painting) as was the norm.

[49] Nearly all of these more abstracted conventions could be observed in the glittering mosaics of the era, which during this period moved from being decoration derivative from painting used on floors (and walls likely to become wet) to a major vehicle of religious art in churches.

He was increasingly given Roman elite status, and shrouded in purple robes like the emperors with orb and scepter in hand — this new type of depiction is variously thought to be derived from either the iconography of Jupiter or of classical philosophers.

[51] In the field of literature, late antiquity is known for the declining use of classical Greek and Latin, and the rise of literary cultures in Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic, Arabic, and Coptic.

[53] One genre of literature among Christian writers in this period was the Hexaemeron, dedicated to the composition of commentaries, homilies, and treatises concerned with the exegesis of the Genesis creation narrative.

[citation needed] Latin poets included Ausonius, Paulinus of Nola, Claudian, Rutilius Namatianus, Orientius, Sidonius Apollinaris, Corippus and Arator.