Frederick W. Lanchester

He supplemented his instruction in applied engineering by attending evening classes at Finsbury Technical School.

About this time he registered a patent for an isometrograph, a draughtsman's instrument for hatching, shading and other geometrical design work.

The couple relocated to 41 Bedford Square, London, but in 1924 Lanchester built a house to his own design (Dyott End) in Oxford Road, Moseley, Birmingham.

He was diagnosed eventually with Parkinson's disease and was reportedly much grieved that this, along with cataracts in both eyes, prevented him from "doing any official job" during the Second World War.

Although he achieved his fame by his creative brilliance as an engineer, Frederick Lanchester was a man of diverse interests, blessed with a fine singing voice.

[9] Lanchester, who had never been successful commercially, lived the remainder of his life in straitened circumstances, and it was only through charitable help that he was able to remain in his home.

His contract of employment included a clause stating that any technical improvements that he made would be the intellectual property of the company.

He subsequently sold the rights for his invention to the Crossley Gas Engine Company for a handsome sum.

In this workshop, he produced a small vertical single cylinder gas engine of 3 bhp (2.2 kW), running at 600 rpm.

At about the same time, he produced a second engine type similar in design to his previous one but operating on benzene at 800 rpm.

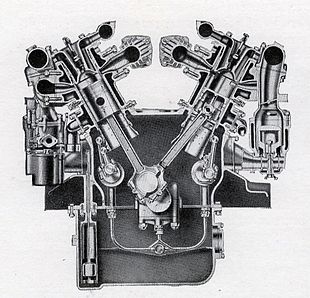

He designed a new petrol engine of 5 bhp (3.7 kW), with two crankshafts rotating in opposite directions, for exemplary smoothness,[10] and air cooling by way of vanes mounted on the flywheel.

[11] There was a revolutionary[11] epicyclic gearbox (years before Henry Ford adopted it)[11] giving two forward speeds plus reverse, and which drove the rear wheels via chains.

[11] (By contrast, Rudolf Egg's tricycle had a 3 hp (2.2 kW) 402 cc {24½in3)[12] de Dion-Bouton single and was capable of 40 km/h {25 mph},[12] and Léon Bollée's trike a 1.9 kW {2.5 hp} 650 cc (40 in3)[12] engine of his own design, capable of over 50 km/h {30 mph}.

[12] Lanchester's car was completed in 1895 and given its first test run in 1896, and proved to be unsatisfactory, being underpowered and having transmission problems.

Lanchester designed a new 8 hp (6 kW) 2,895 cc (177 in3)[11] air-cooled engine with two horizontally opposed cylinders, still with two crankshafts.

Lanchester had relocated his business to larger workshops in Ladywood Road, Fiveways, Birmingham as work on the car progressed and had also sold his house to help finance the cost of his research.

In 1898, Lanchester designed a water-cooled version of his 8 bhp (6.0 kW) engine, which was fitted to a boat, driving a propeller.

In 1900 the Gold Medal Phaeton was entered for the first Royal Automobile Club 1,000 Miles Trial and completed the course successfully after one mechanical failure en route.

[22] The Lanchester Engine Company sold about 350 cars of various designs between 1900 and 1904, when they became bankrupt due to the incompetence of the board of directors.

Eventually Lanchester became disillusioned with the activities of the company's directors, and in 1910 resigned as general manager, becoming their part-time consultant and technical adviser.

In 1909 Lanchester became a technical consultant for the Daimler Company where he became involved in a number of engineering projects including the Daimler-Knight engine, variants of which powered the petrol-electric KPL bus and the Daimler-Renard Road Train,[23] and the first British heavy tanks of World War I and powered all Daimler cars from 1909 to the mid-1930s winning in 1909 the coveted RAC Dewar Trophy.

[25][26] Daimler had put all its resources into this "rather unsatisfactory engine" (according to Harry Ricardo), but although Lanchester continued to develop and work on the design, "he had realised that it was a forlorn hope from the start.

rating) Daimler-Knight engines each coupled to a dynamotor driving one of the rear wheels, using a patent of Henri Pieper.

BSA group, the owners of Daimler since 1910, completed the purchase of the Lanchester company in January 1931 and moved production to Radford, Coventry.

Whilst crossing the Atlantic on a voyage to the United States, Lanchester studied the flight of herring gulls, seeing how they were able to use motionless wings to catch up-currents of air.

In 1897 he presented a paper entitled "The soaring of birds and the possibilities of mechanical flight" to the Physical Society, but it was rejected, being too advanced for its time.

In it, he developed a model for the vortices that occur behind wings during flight,[41] which included the first full description of lift and drag.

His book was not well received in England, but created interest in Germany where the scientist Ludwig Prandtl mathematically confirmed the correctness of Lanchester's vortex theory.

In 1914, before the start of World War I, he published his ideas on aerial warfare in a series of articles in Engineering.

Lanchester was respected by most fellow engineers as a genius, but he did not have the business acumen to convert his inventiveness to financial gain.

Coventry University Library

Gosford Street, Coventry