Heyting algebra

In mathematics, a Heyting algebra (also known as pseudo-Boolean algebra[1]) is a bounded lattice (with join and meet operations written ∨ and ∧ and with least element 0 and greatest element 1) equipped with a binary operation a → b called implication such that (c ∧ a) ≤ b is equivalent to c ≤ (a → b).

From a logical standpoint, A → B is by this definition the weakest proposition for which modus ponens, the inference rule A → B, A ⊢ B, is sound.

Those elements of a Heyting algebra H of the form ¬a comprise a Boolean lattice, but in general this is not a subalgebra of H (see below).

The open sets of any topological space form a complete Heyting algebra.

Complete Heyting algebras thus become a central object of study in pointless topology.

It follows that even among the finite Heyting algebras there exist infinitely many that are subdirectly irreducible, no two of which have the same equational theory.

Given a bounded lattice A with largest and smallest elements 1 and 0, and a binary operation →, these together form a Heyting algebra if and only if the following hold: where equation 4 is the distributive law for →.

, and the constants 0 and 1), it is a fact, proved early on in any study of Heyting algebras, that the following two conditions are equivalent: The metaimplication 1 ⇒ 2 is extremely useful and is the principal practical method for proving identities in Heyting algebras.

For example, let us choose the system of proof having modus ponens as its sole rule of inference, and whose axioms are the Hilbert-style ones given at Intuitionistic logic#Axiomatization.

Then the facts to be verified follow immediately from the axiom-like definition of Heyting algebras given above.

Specifically, we always have the identities The distributive law is sometimes stated as an axiom, but in fact it follows from the existence of relative pseudo-complements.

An element x of a Heyting algebra H is called regular if either of the following equivalent conditions hold: The equivalence of these conditions can be restated simply as the identity ¬¬¬x = ¬x, valid for all x in H. Elements x and y of a Heyting algebra H are called complements to each other if x∧y = 0 and x∨y = 1.

Any complemented element of a Heyting algebra is regular, though the converse is not true in general.

For any Heyting algebra H, the following conditions are equivalent: In this case, the element a→b is equal to ¬a ∨ b.

Condition 6 says that the join operation ∨reg on the Boolean algebra Hreg of regular elements of H coincides with the operation ∨ of H. Condition 7 states that every regular element is complemented, i.e., Hreg = Hcomp.

Furthermore, 3 ⇔ 4 and 5 ⇔ 6 result simply from the first De Morgan law and the definition of regular elements.

The metaimplication 5 ⇒ 2 is a trivial consequence of the weak De Morgan law, taking ¬x and ¬y in place of x and y in 5.

Assume H1 and H2 are structures with operations →, ∧, ∨ (and possibly ¬) and constants 0 and 1, and f is a surjective mapping from H1 to H2 with properties 1 through 4 above.

In other words, ≤ is the order relation on L/~ induced by the preorder ≼ on L. In fact, the preceding construction can be carried out for any set of variables {Ai : i∈I} (possibly infinite).

It is free in the sense that given any Heyting algebra H given together with a family of its elements 〈ai: i∈I 〉, there is a unique morphism f:H0→H satisfying f([Ai])=ai.

The uniqueness of f is not difficult to see, and its existence results essentially from the metaimplication 1 ⇒ 2 of the section "Provable identities" above, in the form of its corollary that whenever F and G are provably equivalent formulas, F(〈ai〉)=G(〈ai〉) for any family of elements 〈ai〉in H. Given a set of formulas T in the variables {Ai}, viewed as axioms, the same construction could have been carried out with respect to a relation F≼G defined on L to mean that G is a provable consequence of F and the set of axioms T. Let us denote by HT the Heyting algebra so obtained.

The existence and uniqueness of the morphism is proved the same way as for H0, except that one must modify the metaimplication 1 ⇒ 2 in "Provable identities" so that 1 reads "provably true from T," and 2 reads "any elements a1, a2,..., an in H satisfying the formulas of T." The Heyting algebra HT that we have just defined can be viewed as a quotient of the free Heyting algebra H0 on the same set of variables, by applying the universal property of H0 with respect to HT, and the family of its elements 〈[Ai]〉.

In fact, The Lindenbaum algebra BT in the variables {Ai} with respect to the axioms T is just our HT∪T1, where T1 is the set of all formulas of the form ¬¬F→F, since the additional axioms of T1 are the only ones that need to be added in order to make all classical tautologies provable.

This means that if a formula is deducible from the laws of intuitionistic logic, being derived from its axioms by way of the rule of modus ponens, then it will always have the value 1 in all Heyting algebras under any assignment of values to the formula's variables.

A Heyting algebra, from the logical standpoint, is then a generalization of the usual system of truth values, and its largest element 1 is analogous to 'true'.

The problem of whether a given equation holds in every Heyting algebra was shown to be decidable by Saul Kripke in 1965.

[3] The precise computational complexity of the problem was established by Richard Statman in 1979, who showed it was PSPACE-complete[12] and hence at least as hard as deciding equations of Boolean algebra (shown coNP-complete in 1971 by Stephen Cook)[13] and conjectured to be considerably harder.

[14] It remains open whether the universal Horn theory of Heyting algebras, or word problem, is decidable.

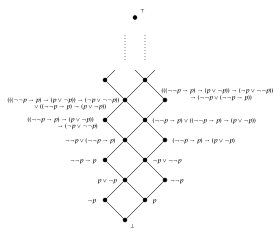

It is unknown whether free complete Heyting algebras exist except in the case of a single generator where the free Heyting algebra on one generator is trivially completable by adjoining a new top.

Every Heyting algebra H is naturally isomorphic to a bounded sublattice L of open sets of a topological space X, where the implication