Free flight (model aircraft)

Free flight is the segment of model aviation involving aircraft with no active external control after launch.

Their stability is achieved by a combination of design and trim, - the relationship between centre of gravity, wing and tailplane incidence and rudder setting.

These outdoor free flight models tend to be designed for two very different flying modes: climbing rapidly under power or tow, and gliding slowly while circling with minimum fall rate.

Much of the challenge in designing and flying these models is to maintain aerodynamic stability in both modes and to make a smooth transition between them.

Detecting the thermal into which to launch is vital and can involve several methods, ranging from radio telemetered temperature and wind speed measurements plotted on a chart recorder to Mylar streamers or soap bubbles to visualize the rising air.

Competitions normally involve up to seven rounds during the day, each flown to a maximum flight time hard to achieve without thermal assistance.

A day's flying and retrieval may well involve 20 miles (32 km) or so on foot or on bike, depending on wind strength.

Models flown indoors do not depend on rising air currents, but they must be designed for maximum flight efficiency because of the limited energy stored in the rubber or electric power source.

Using this initial burst efficiently is vital, and automatic variable-pitch propellers help here, together with timer-operated changes of wing and tailplane incidence and of rudder setting.

At the end of the power run the blades fold back alongside the fuselage to minimise drag during the glide.

The rules and dimension restrictions vary every year, but many notable fliers such as Brett Sanborn started in Science Olympiad.

Planes for this competition usually consist of a balsa frame with a mylar-covered wing and a commercially available fixed-pitch propeller.

The smallest rubber powered model aircraft was built in 1931 by a Philadelphia high school student, called the Flying Flea and was one and a quarter inches long and could remain airborne for approximately one minute.

Designing an aircraft which climbs as high as possible, with minimum drag at a low lift coefficient, but then must convert to a slow flying glider, is a challenge unique in aviation.

These engines are usually custom made for optimal power output and often yield 1 hp (0.75 kW) at more than 30,000 RPM.

These models are constructed from light balsa sheet and strip, boron filament, carbon fibre, and a transparent covering of plastic film less than 0.5 micrometres thick.

The models are powered by 0.4 grams of rubber in a single loop about 9.0 inches long that can be wound to take around 1500 turns.

F1D models require a large space, such as a sports hall, aircraft or dirigible hangar, with the famous atrium of the West Baden Springs Hotel having been previously used for indoor free flight competitions in the United States, and there is even a salt mine in Romania 400 feet (120 m) underground that has hosted the FAI world F1D championships several times.

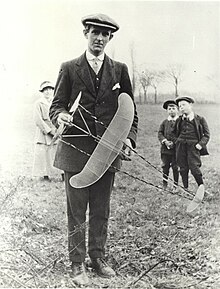

Jim Arnott holds Winding Boy, a classic rubber model designed by Urlan Wannop.

Old Timer free flight aircraft specifications, competition rules and guidelines are available from the SAM organization online.

The flying duration of the scale model is greatly increased because of the number of windings that can be made on such a long loop of rubber with multiple strands.

A mechanical winder is used and the rubber is stretched up to fives times original length to pack in maximum winds on the motor.

Experts can achieve spectacular flights from obscure designs such as the Wright brothers original and Bleriot's channel crosser, to one-of-a-kind Depression era homebuilts and modern day experimental aircraft.