Free will in antiquity

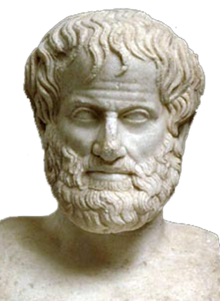

Michael Frede typifies the prevailing view of recent scholarship, namely that Aristotle did not have a notion of free-will.

Indeed, the problem was not discovered until Hellenistic times, perhaps by Epicurus, who was over forty years junior to Aristotle, and who reached Athens just too late to hear his lectures.

Writing one generation after Aristotle, Epicurus argued that as atoms moved through the void, there were occasions when they would "swerve" (clinamen) from their otherwise determined paths, thus initiating new causal chains.

But following Aristotle, Epicurus thought human agents have the autonomous ability to transcend necessity and chance (both of which destroy responsibility), so that praise and blame are appropriate.

Epicurus finds a tertium quid (a third option), beyond necessity (Democritus' physics) and beyond Aristotle's chance.

...necessity destroys responsibility and chance is inconstant; whereas our own actions are autonomous, and it is to them that praise and blame naturally attach.

It is unfortunate that our knowledge of the early history of the Stoics is so fragmentary, and that we have no agreed account of the relations between them and Epicurus.

On the evidence we have, however, it seems to me more probable that Epicurus was the originator of the freewill controversy, and that it was only taken up with enthusiasm among the Stoics by Chrysippus, the third head of the school.

[9]In 2000, Susanne Bobzien challenged Pamela Huby's 1967 assertion that Epicurus discovered the "free-will problem".

Long and D. N. Sedley, however, agree with Pamela Huby that Epicurus was the first to notice the modern problem of free will and determinism.

[11]One view, going back to the 19th century historian Carlo Giussani, is that Epicurus' atomic swerves are involved directly in every case of human free action, not just somewhere in the past that breaks the causal chain of determinism.

Bailey imagined complexes of mind-atoms that work together to form a consciousness that is not determined, but also not susceptible to the pure randomness of individual atomic swerves, something that could constitute Epicurus' idea of actions being "up to us" (πὰρ' ἡμάς).

It may be that [Giussani's] account presses the Epicurean doctrine slightly beyond the point to which the master had thought it out for himself, but it is a direct deduction from undoubted Epicurean conceptions and is a satisfactory explanation of what Epicurus meant: that he should have thought that the freedom of the will was chance, and fought hard to maintain it as chance and no more, is inconceivable.

If we now put together the introduction to Lucretius' passage on voluntas and Aristotle's theory of the voluntary, we can see how the swerve of atoms was supposed to do its work.

All he needs to satisfy the Aristotelian criterion is a break in the succession of causes, so that the source of an action cannot be traced back to something occurring before the birth of the agent.

[15] On the other hand, in his 1983 thesis, "Lucretius on the Clinamen and 'Free Will'", Don Paul Fowler defended the ancient claim that Epicurus proposed random swerves as directly causing our actions.

Furley, however, argued that the relationship between voluntas and the clinamen was very different; not every act of volition was accompanied by a swerve in the soul-atoms, but the clinamen was only an occasional event which broke the chain of causation between the σύστασις of our mind at birth and the 'engendered' state (τὸ ἀπογεγεννημένον) which determines our actions.Its role in Epicureanism is merely to make a formal break with physical determinism, and it has no real effect on the outcome of particular actions.

Chrysippus said our actions are determined (in part by ourselves as causes) and fated (because of God's foreknowledge), but he also said that they are not necessitated, i.e., pre-determined from the distant past.

R. W. Sharples describes the first compatibilist arguments to reconcile responsibility and determinism by Chrysippus The Stoic position, given definitive expression by Chrysippus (c. 280–207 BC), the third head of the school, represents not the opposite extreme from that of Epicurus but an attempt to compromise, to combine determinism and responsibility.

Their theory of the universe is indeed a completely deterministic one; everything is governed by fate, identified with the sequence of causes; nothing could happen otherwise than it does, and in any given set of circumstances one and only one result can follow – otherwise an uncaused motion would occur.

[19] The Peripatetic philosopher Alexander of Aphrodisias (c. 150–210), the most famous of the ancient commentators on Aristotle, defended a view of moral responsibility we would call libertarianism today.

Greek philosophy had no precise term for "free will" as did Latin (liberum arbitrium or libera voluntas).

R. W. Sharples described Alexander's De Fato as perhaps the most comprehensive treatment surviving from classical antiquity of the problem of responsibility (τὸ ἐφ’ ἡμίν) and determinism.

It especially shed a great deal of light on Aristotle's position on free will and on the Stoic attempt to make responsibility compatible with determinism.

"[28] However, McGrath also notes: "The pre-Augustinian theological tradition is practically of one voice in asserting the freedom of the human will.

"[29] Oxford Professor Suzanne Bobzien writes that the first evidence of a notion of indeterminist view of free will is found in Alexander of Aphrodisias (ca.

Semi-Pelagianism was a moderate form of Pelagianism which teaches that the first step of salvation is by human will and not the grace of God.

[40][41][42] It defined that faith, though a free act of man, resulted, even in its beginnings, from the grace of God, enlightening the human mind and enabling belief.

[46][47] On the other hand, the Council of Orange condemned the belief in predestination to damnation[48] implied by the Augustinian soteriology.

[51] Likewise, the Remonstrants and later Arminians/Wesleyans have been aligned with the Semi-Augustinian position of the canons of the Second Council of Orange concerning free will.