French Cameroon

The German protectorate commenced in 1884 with a treaty with local chiefs in the Douala area, in particular Ndumbe Lobe Bell, then gradually it was extended to the interior.

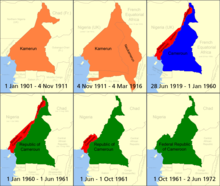

During World War I, the German protectorate was occupied by British and French troops, and later mandated to each country by the League of Nations in 1922.

An insurrection headed by Ruben Um Nyobé and the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC) erupted in 1955, strongly repressed by the French Fourth Republic.

France enacted an assimilationist policy with the aim of having German presence forgotten, by teaching French on all of the territory and imposing French law, while pursuing the "indigenous politics", which consisted of keeping control of the judiciary system and of the police, while tolerating traditional law issues.

The colonial administration also followed public health policies (Eugène Jamot did some research on sleeping sickness) as well as encouraging Francophony.

France took care to make disappear all remains of German presence and aimed at eradicating any trace of Germanophilia.

Troops under General Philippe Leclerc landed at Douala, capturing it on 27 August, and then moved to Yaounde, where pro-Vichy France governor Richard Brunot surrendered the civil administration.

From the beginning of the 1940s, colonial authorities encouraged a policy of agricultural diversification into monocultural crops: coffee in the west, cotton in the North and cocoa in the south.

Of a total of three million inhabitants, the French Cameroon territory counted 10% settlers, many who had been resident for decades, and approximatively 15,000 people linked to the colonial administration (civil servants, private agents, missionaries etc.)

The Cameroon War then escalated and lasted for at least seven years, with the French Fourth Republic leading a harsh repression of the anti-colonialist movement.

In 1957–58, Pierre Messmer, a Gaullist and head of the haut-commissaire of Cameroon (executive branch of the French government) started a decolonisation process which went further than the 1956 loi-Defferre (Defferre Act).

André Bdida renounced in 1958, replaced by Ahidjo, while Um Nyobé was killed by a French commando in the "maquis" on 13 September 1958.

The rebellion was really crushed only in the 1970s, after the death in the "maquis" of Ossendé Afana in March 1966 and the public execution of Ernest Ouandié, a historic leader of the UPC, in January 1971.

The lack interest has been attributed to the use of professional soldiers in the conflict, the low number of Cameroonian immigrants in France requesting recognition of the crimes committed during the war, and, more recently, the fall of Communism.