Charles de Gaulle

As early as 1944, De Gaulle introduced a dirigiste economic policy, which included substantial state-directed control over a capitalist economy, which was followed by 30 years of unprecedented growth, known as the Trente Glorieuses.

In the context of the Cold War, De Gaulle initiated his "politics of grandeur", asserting that France as a major power should not rely on other countries, such as the United States, for its national security and prosperity.

In his later years, his support for the slogan "Vive le Québec libre" and his two vetoes of Britain's entry into the European Economic Community generated considerable controversy in both North America and Europe.

He also appears to have accepted the then fashionable lesson drawn from the recent Russo-Japanese War, of how bayonet charges by Japanese infantry with high morale had succeeded in the face of enemy firepower.

However, the French Fifth Army commander, General Charles Lanrezac, remained wedded to 19th-century battle tactics, throwing his units into pointless bayonet charges against German artillery, incurring heavy losses.

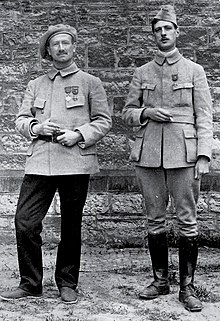

[15] As a company commander at Douaumont (during the Battle of Verdun) on 2 March 1916, while leading a charge to try to break out of a position which had become surrounded, he received a bayonet wound to the left thigh after being stunned by a shell and was captured after passing out from the effects of poison gas.

Moyrand wrote in his final report that he was "an intelligent, cultured and serious-minded officer; has brilliance and talent" but criticised him for not deriving as much benefit from the course as he should have, and for his arrogance: his "excessive self-confidence", his harsh dismissal of the views of others "and his attitude of a King in exile".

[45] Pétain instead advised him to apply for a posting to the Secrétariat Général du Conseil Supérieur de la Défense Nationale (SGDN – General Secretariat of the Supreme War Council) in Paris.

Lacouture suggests that Mayer focused de Gaulle's thoughts away from his obsession with the mystique of the strong leader (Le Fil d'Epée: 1932) and back to loyalty to Republican institutions and military reform.

[66] That day, with three tank battalions assembled, less than a third of his paper strength, he was summoned to headquarters and told to attack to gain time for General Robert Touchon's Sixth Army to redeploy from the Maginot Line to the Aisne.

After visiting his tailor to be fitted for his general's uniform, he met Reynaud, who appears to have offered him a government job for the first time, and afterwards the commander-in-chief Maxime Weygand, who congratulated him on saving France's honour and asked for his advice.

[73] On 5 June, the day the Germans began the second phase of their offensive (Fall Rot), Prime Minister Paul Reynaud appointed de Gaulle Under-Secretary of State for National Defence and War,[74] with particular responsibility for coordination with the British.

[94] Eisenhower was impressed by the combativeness of units of the Free French Forces and "grateful for the part they had played in mopping up the remnants of German resistance"; he also detected how strongly devoted many were to de Gaulle and how ready they were to accept him as the national leader.

[3] De Gaulle successfully lobbied for Paris to be made a priority for liberation on humanitarian grounds and obtained from Allied supreme commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower an agreement that French troops would be allowed to enter the capital first.

"[103] At an official luncheon, de Gaulle said: It is true that we would not have seen [the liberation] if our old and gallant ally England, and all the British dominions under precisely the impulsion and inspiration of those we are honouring today, had not deployed the extraordinary determination to win, and that magnificent courage which saved the freedom of the world.

Knowing that he would need to reprieve many of the 'economic collaborators'—such as police and civil servants who held minor roles under Vichy to keep the country running—he assumed, as head of state, the right to commute death sentences.

[111] On 13 November 1945, the new assembly unanimously elected Charles de Gaulle head of the government, but problems immediately arose when it came to selecting the cabinet, due to his unwillingness to allow the Communists any important ministries.

[7] Eventually, the new cabinet was finalised on 21 November, with the Communists receiving five out of the twenty-two ministries, and although they still did not get any key portfolios, de Gaulle believed that the draft constitution placed too much power in the hands of parliament with its shifting party alliances.

[19] In April 1947, de Gaulle made a renewed attempt to transform the political scene by creating a Rassemblement du Peuple Français (Rally of the French People, RPF), which he hoped would be able to move above the party squabbles of the parliamentary system.

[117] Although de Gaulle had moved quickly to consolidate French control of the territory during his brief first tenure as president in the 1940s, the communist Vietminh under Ho Chi Minh began a determined campaign for independence from 1946.

[123] Political leaders on many sides agreed to support the General's return to power, except François Mitterrand, Pierre Mendès France, Alain Savary, the Communist Party, and certain other leftists.

On 29 May the French President, René Coty, told parliament that the nation was on the brink of civil war, so he was turning towards the most illustrious of Frenchmen, towards the man who, in the darkest years of our history, was our chief for the reconquest of freedom and who refused dictatorship in order to re-establish the Republic.

I ask General de Gaulle to confer with the head of state and to examine with him what, in the framework of Republican legality, is necessary for the immediate formation of a government of national safety and what can be done, in a fairly short time, for a deep reform of our institutions.

As the last chief of government of the Fourth Republic, de Gaulle made sure that the Treaty of Rome creating the European Economic Community was fully implemented, and that the British project of Free Trade Area was rejected, to the extent that he was sometimes considered as a "Father of Europe".

With the Algerian conflict behind him, de Gaulle was able to achieve his two main objectives, the reform and development of the French economy, and the promotion of an independent foreign policy and a strong presence on the international stage.

Germany was in an even worse position, but after 1948 things began to improve dramatically with the introduction of Marshall Aid—large scale American financial assistance given to help rebuild European economies and infrastructure.

This surprising statement was intended as a declaration of French national independence and was in retaliation to a warning issued long ago by Dean Rusk that US missiles would be aimed at France if it attempted to employ atomic weapons outside an agreed plan.

[162] In his letter to David Ben-Gurion dated 9 January 1968, de Gaulle expressed conviction that Israel had ignored his warnings and overstepped the bounds of moderation by taking the territory of neighbouring countries by force, believing that it amounted to annexation, and considered withdrawing from these areas the best course of action.

[182] Since a large number of foreign dignitaries wanted to honor de Gaulle, Pompidou arranged a separate memorial service at the Notre-Dame Cathedral, to be held at the same time as the actual funeral.

Mitterrand, who once wrote a vitriolic critique of him called the "Permanent Coup d'État", quoted a recent opinion poll, saying, "As General de Gaulle, he has entered the pantheon of great national heroes, where he ranks ahead of Napoleon and behind only Charlemagne.