French entry into World War I

Russia decided to intervene to protect Serbia due to its interest in the Balkan region and its desire to gain an advantage over Austria-Hungary.

[2] Bismarck, in the hope of making the Tsar more amenable to his wishes, had forbidden German banks to lend money to Russia.

This diplomatic coup was followed by a secret agreement with Italy, allowing the Italians a free hand to expand in Tripoli (modern Libya, then still under Turkish rule).

The French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé was aware that France could not progress if she was in conflict with Germany in Europe and Britain in Africa, and so recalled Captain Marchand's expeditionary force from Fashoda, despite popular protests.

The Moroccan Crises of 1905 and 1911 encouraged both countries to embark on a series of secret military negotiations in the case of war with Germany.

However, British Foreign Minister Edward Grey realized the risk that small conflicts between Paris and Berlin could escalate out of control.

Working with little supervision from the British Prime Minister or Cabinet, Grey deliberately played a mediating role, trying to calm both sides and thereby maintain a peaceful balance of power.

The Liberal government of Britain was pacifistic, and also extremely legalistic, so that German violation of Belgium neutrality – treating it like a scrap of paper – helped mobilize party members to support the war effort.

The decisive factors were twofold, Britain felt a sense of obligation to defend France, and the Liberal Government realized that unless it did so, it would collapse either into a coalition, or yield control to the more militaristic Conservative Party.

When the German army invaded Belgium, not only was neutrality violated, but France was threatened with defeat, so the British government went to war.

Socialists, led by Jean Jaurès, deeply believed that war was a capitalist plot and could never be beneficial to the working man.

Paris had relatively little involvement in the Balkan crisis that launched the war, paying little attention to Serbia, Austria or the Ottoman Empire.

"[9] Although the issue of Alsace-Lorraine faded in importance after 1880, the rapid growth in the population and economy of Germany left France increasingly far behind.

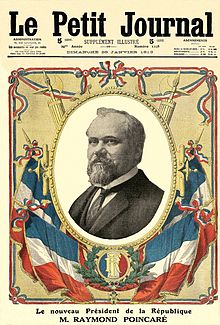

Raymond Poincaré's speeches as Prime Minister in 1912, and then as president in 1913–14, were similarly firm and drew widespread support across the political spectrum.

[12] However Jaurès was assassinated on 31 July, and the socialist parties in both France and Germany – as well as most other countries – strongly supported their national war effort in the first year.

He was frustrated by French leaders such as Raymond Poincaré, who decided Berlin was trying to weaken the Triple Entente of France, Russia and Britain, and was not sincere in seeking peace.

[15] President Raymond Poincaré was the most important decision maker, a highly skilled lawyer with a dominant personality and a hatred for Germany.

[16] The central policy goal for Poincaré was maintaining the close alliance with Russia, which he achieved by a week-long visit to St. Petersburg in mid-July 1914.

The crisis was caused not by the assassination but rather by the decision in Vienna to use it as a pretext for a war with Serbia that many in the Austrian and Hungarian governments had long advocated.

[20] A year before, it had been planned that French President Raymond Poincaré would visit St Petersburg in July 1914 to meet Tsar Nicholas II.

The Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, Count Berchtold, decided that it was too dangerous for Austria-Hungary to present the ultimatum while the Franco-Russian summit was in progress.

[21] At the time of the St Petersburg summit, there were rumours but little hard evidence that Vienna might use the assassination to start a war with Serbia.

[22][23] The French and the Russians agreed that their alliance extended to supporting Serbia against Austria, confirming the already-established policy behind the Balkan inception scenario.

At no point do the sources suggest that Poincaré or his Russian interlocutors gave any thought whatsoever to what measures Austria-Hungary might legitimately be entitled to take in the aftermath of the assassinations".

[25] Just the opposite took place: without co-ordination, Russia assumed it had France's full support and so Austria sabotaged its own hopes for localisation.

In St Petersburg, most Russian leaders sensed that their national strength was gaining on Germany and Austria and so it would be prudent to wait until they were stronger.

[29] When Vienna's ultimatum was presented to Serbia on 23 July, the French government was in the hands of Acting Premier Jean-Baptiste Bienvenu-Martin, the Minister of Justice, who was unfamiliar with foreign affairs.

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg told his assistant that Britain and France did not realize that Germany would go to war if Russia mobilized.

[32] Political scientist James Fearon argued from this episode that the Germans believed Russia to be expressing greater verbal support for Serbia than it would actually provide to pressure Germany and Austria-Hungary to accept some Russian demands in negotiation.

France was a major military and diplomatic player before and after the July crisis, and every power paid close attention to its role.