Feminism in France

Pioneered by theorists such as Simone de Beauvoir, second wave feminism was an important current within the social turmoil leading up to and following the May 1968 events in France.

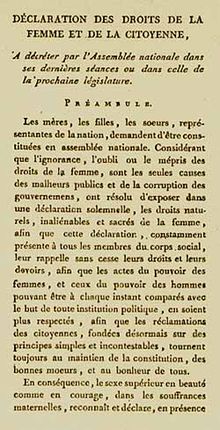

Although various feminist movements emerged during the Revolution, most politicians followed Rousseau's theories as outlined in Emile, which confined women to the roles of mother and spouse.

They claimed equality of rights and participated in the abundant literary activity, such as Claire Démar's Appel au peuple sur l'affranchissement de la femme (1833), a feminist pamphlet.

During the culturally thriving times of the Belle Époque, especially in the late nineteenth century, feminism and the view of femininity experienced substantial shifts evident through acts by women of boldness and rejection of previous stigmas.

[3] Such acts included these women partaking in nonstandard ways of marriage—as divorce during this time had been legally reinstalled as a result of the Naquet Laws[4]—practicing gender role-defying jobs, and profoundly influencing societal ideologies regarding femininity through writings.

Nathalie Lemel, a socialist bookbinder, and Élisabeth Dmitrieff, a young Russian exile and member of the Russian section of the First International (IWA), created the Union des femmes pour la défense de Paris et les soins aux blessés ("Women's Union for the Defense of Paris and Care of the Injured") on 11 April 1871.

They also demanded suppression of the distinction between married women and concubines, between legitimate and natural children, the abolition of prostitution in closing the maisons de tolérance, or legal official brothels.

[7] Along with Eugène Varlin, Nathalie Le Mel created the cooperative restaurant La Marmite, which served free food for indigents, and then fought during the Bloody Week on the barricades.

[8] On the other hand, Paule Minck opened a free school in the Church of Saint Pierre de Montmartre, and animated the Club Saint-Sulpice on the Left Bank.

[8] Famous figures such as Louise Michel, the "Red Virgin of Montmartre" who joined the National Guard and would later be sent to New Caledonia, symbolize the active participation of a small number of women in the insurrectionary events.

Despite some cultural changes following World War I, which had resulted in women replacing the male workers who had gone to the front, they were known as the Années folles and their exuberance was restricted to a very small group of female elites.

[9] The suffragettes, however, did honour the achievements of foreign women in power by bringing attention to legislation passed under their influence concerning alcohol (such as Prohibition in the United States), regulation of prostitution, and protection of children's rights.

The paternal authority of a man over his family in France was ended in 1970 (before that parental responsibilities belonged solely to the father who made all legal decisions concerning the children).

[33] On the other hand, a "third wave" of the feminist movement arose, combining the issues of sexism and racism, protesting the perceived Islamophobic instrumentalization of feminism by the French Right.

as well as NGOs such as Les Blédardes (led by Bouteldja), criticized the racist stigmatization of immigrant populations, whose cultures are depicted as inherently sexist.

[34][35] They frame the debate among the French Left concerning the 2004 law on secularity and conspicuous religious symbols in schools, mainly targeted against the hijab, under this light.

[38] The manifesto stated that "Western Feminism did not have the monopoly of resistance against masculine domination" and supported a mild form of separatism, refusing to allow others (males or whites) to speak in their names.

In 1936, the new Prime Minister, Léon Blum, included three women in the Popular Front government: Cécile Brunschvicg, Suzanne Lacore and Irène Joliot-Curie.

Marie-France Garaud, who entered Jean Foyer's office at the Ministry of Cooperation and would later become President Georges Pompidou's main counsellor, along with Pierre Juillet, was given the same title.

SFIO member Andrée Viénot, widow of a Resistant, was nominated in June 1946 by the Christian democrat Georges Bidault of the Popular Republican Movement as undersecretary of Youth and Sports.

The next woman to hold government office, Germaine Poinso-Chapuis, was health and education minister from 24 November 1947 to 19 July 1948 in Robert Schuman's cabinet.

The Communist and the Radical-Socialist Party called for the repealing of the decree, and finally, Schuman's cabinet was overturned after failing a confidence motion on the subject.

[9] The third woman to hold government office would be the Radical-Socialist Jacqueline Thome-Patenôtre, appointed undersecretary of Reconstruction and Lodging in Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury's cabinet in 1957.

[9] Historians explain this rarity by underlining the specific context of the Trente Glorieuses (Thirty Glorious Years) and of the baby boom, leading to a strengthening of familialism and patriarchy.

Janine Alexandre-Derbay, 67-year-old senator of the Republican Party (PR), initiated a hunger strike to protest against the complete absence of women on the governmental majority's electoral lists in Paris.

Giscard's achievements concerning the inclusion of women in government has been qualified by Françoise Giroud as his most important feat, while others, such as Evelyne Surrot, Benoîte Groult or the minister Monique Pelletier, denounced electoral "alibis".

The sociologist Mariette Sineau underlined that Giscard included women only in the low-levels of the governmental hierarchy (state secretaries) and kept them in socio-educative affairs.

[citation needed] She was a front-runner in their leadership election, which took place 20 November 2008 but was narrowly defeated in the second round by rival Martine Aubry, also a woman.

"[41] Christine Bard, a professor at the University of Angers, echoed those thoughts, saying that there is an "idealization of seduction à la Française, and that anti-feminism has become almost part of the national identity" in France.

In 1992, the Court of Cassation convicted a man of the rape of his wife, stating that the presumption that spouses have consented to sexual acts that occur within marriage is only valid when the contrary is not proven.