Augustin-Jean Fresnel

The simpler dioptric (purely refractive) stepped lens, first proposed by Count Buffon [4] and independently reinvented by Fresnel, is used in screen magnifiers and in condenser lenses for overhead projectors.

Although he did not become a public celebrity in his lifetime, he lived just long enough to receive due recognition from his peers, including (on his deathbed) the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society of London, and his name is ubiquitous in the modern terminology of optics and waves.

[22] At the age of nine or ten he was undistinguished except for his ability to turn tree-branches into toy bows and guns that worked far too well, earning himself the title l'homme de génie (the man of genius) from his accomplices, and a united crackdown from their elders.

[41]) In March 1815, perceiving Napoleon's return from Elba as "an attack on civilization",[42] Fresnel departed without leave, hastened to Toulouse and offered his services to the royalist resistance, but soon found himself on the sick list.

The corpuscular theory of light, favored by Isaac Newton and accepted by nearly all of Fresnel's seniors, easily explained rectilinear propagation: the corpuscles obviously moved very fast, so that their paths were very nearly straight.

[61] It was not until 1801 that Thomas Young, in the Bakerian Lecture for that year, cited Newton's hint,[62]: 18–19 and accounted for the colors of a thin plate as the combined effect of the front and back reflections, which reinforce or cancel each other according to the wavelength and the thickness.

[81] In 1812, as Arago pursued further qualitative experiments and other commitments, Jean-Baptiste Biot reworked the same ground using a gypsum lamina in place of the mica, and found empirical formulae for the intensities of the ordinary and extraordinary images.

In the same paragraph, however, Fresnel implicitly acknowledged doubt about the novelty of his work: noting that he would need to incur some expense in order to improve his measurements, he wanted to know "whether this is not useless, and whether the law of diffraction has not already been established by sufficiently exact experiments."

[101] On 10 November, Fresnel sent a supplementary note dealing with Newton's rings and with gratings,[102] including, for the first time, transmission gratings—although in that case the interfering rays were still assumed to be "inflected", and the experimental verification was inadequate because it used only two threads.

[104] On 8 November, Arago wrote to Fresnel: I have been instructed by the Institute to examine your memoir on the diffraction of light; I have studied it carefully, and found many interesting experiments, some of which had already been done by Dr. Thomas Young, who in general regards this phenomenon in a manner rather analogous to the one you have adopted.

In his final "Memoir on the diffraction of light",[137] deposited on 29 July [138] and bearing the Latin epigraph "Natura simplex et fecunda" ("Nature simple and fertile"),[139] Fresnel slightly expanded the two tables without changing the existing figures, except for a correction to the first minimum of intensity.

Then, applying his theory of interference to the secondary waves, he expressed the intensity of light diffracted by a single straight edge (half-plane) in terms of integrals which involved the dimensions of the problem, but which could be converted to the normalized forms above.

1") was mentioned only in the last paragraph of the judges' report,[148] noting that the author had shown ignorance of the relevant earlier works of Young and Fresnel, used insufficiently precise methods of observation, overlooked known phenomena, and made obvious errors.

In July or August 1816, Fresnel discovered that when a birefringent crystal produced two images of a single slit, he could not obtain the usual two-slit interference pattern, even if he compensated for the different propagation times.

[167] In a memoir drafted on 30 August 1816 and revised on 6 October, Fresnel reported an experiment in which he placed two matching thin laminae in a double-slit apparatus—one over each slit, with their optic axes perpendicular—and obtained two interference patterns offset in opposite directions, with perpendicular polarizations.

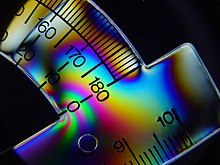

Light that had been converted from linear to elliptical or circular polarization (e.g., by passage through a crystal lamina, or by total internal reflection) was described as partly or fully "depolarized" because of its behavior in an analyzer.

[195]: 760 When light passes through a slice of calcite cut perpendicular to its optic axis, the difference between the propagation times of the ordinary and extraordinary waves has a second-order dependence on the angle of incidence.

[217] But, in a memoir submitted [Note 9] on 19 November 1821,[218] Fresnel reported two experiments on topaz showing that neither refraction was ordinary in the sense of satisfying Snell's law; that is, neither ray was the product of spherical secondary waves.

[227] Later commentators[228]: 19 put the equation in the more compact and memorable form Earlier in the "second supplement", Fresnel modeled the medium as an array of point-masses and found that the force-displacement relation was described by a symmetric matrix, confirming the existence of three mutually perpendicular axes on which the displacement produced a parallel force.

[240] Fresnel's own model was not dynamically rigorous; for example, it deduced the reaction to a shear strain by considering the displacement of one particle while all others were fixed, and it assumed that the stiffness determined the wave velocity as in a stretched string, whatever the direction of the wave-normal.

Starting from assumed equations of motion of a fluid medium, he noted that they did not give the correct results for partial reflection and double refraction—as if that were Fresnel's problem rather than his own—and that the predicted waves, even if they were initially transverse, became more longitudinal as they propagated.

[258] In 1826, the British astronomer John Herschel, who was working on a book-length article on light for the Encyclopædia Metropolitana, addressed three questions to Fresnel concerning double refraction, partial reflection, and their relation to polarization.

[278] By the end of August 1819, unaware of the Buffon-Condorcet-Brewster proposal,[272][132] Fresnel made his first presentation to the commission,[279] recommending what he called lentilles à échelons (lenses by steps) to replace the reflectors then in use, which reflected only about half of the incident light.

The first fixed lens with toroidal prisms was a first-order apparatus designed by the Scottish engineer Alan Stevenson under the guidance of Léonor Fresnel, and fabricated by Isaac Cookson & Co. from French glass; it entered service at the Isle of May in 1836.

[9] Meanwhile, in Britain, the wave theory was yet to take hold; Fresnel wrote to Thomas Young in November 1824, saying in part: I am far from denying the value that I attach to the praise of English scholars, or pretending that they would not have flattered me agreeably.

[311] Fresnel's health, which had always been poor, deteriorated in the winter of 1822–1823, increasing the urgency of his original research, and (in part) preventing him from contributing an article on polarization and double refraction for the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Fresnel, in De la Lumière and in the second supplement to his first memoir on double refraction, suggested that dispersion could be accounted for if the particles of the medium exerted forces on each other over distances that were significant fractions of a wavelength.

[336] No such note appeared in print, and the relevant manuscripts found after his death showed only that, around 1824, he was comparing refractive indices (measured by Fraunhofer) with a theoretical formula, the meaning of which was not fully explained.

If we were to do this, we must consider Huyghens and Hooke as standing in the place of Copernicus, since, like him, they announced the true theory, but left it to a future age to give it development and mechanical confirmation; Malus and Brewster, grouping them together, correspond to Tycho Brahe and Kepler, laborious in accumulating observations, inventive and happy in discovering laws of phenomena; and Young and Fresnel combined, make up the Newton of optical science.

The second revision, initiated by Einstein's explanation of the photoelectric effect, supposed that the energy of light waves was divided into quanta, which were eventually identified with particles called photons.

"Augustin Fresnel, engineer of Bridges and Roads, member of the Academy of Sciences, creator of lenticular lighthouses, was born in this house on 10 May 1788. The theory of light owes to this emulator of Newton the highest concepts and the most useful applications." [ 7 ] [ 10 ]