Frida Kahlo

Inspired by the country's popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society.

During this time, she developed her artistic style, drawing her main inspiration from Mexican folk culture, and painted mostly small self-portraits that mixed elements from pre-Columbian and Catholic beliefs.

[18] Her early paintings and correspondence show that she drew inspiration especially from European artists, in particular Renaissance masters such as Sandro Botticelli and Bronzino[19] and from avant-garde movements such as Neue Sachlichkeit and Cubism.

[36] Despite the popularity of the mural in Mexican art at the time, she adopted a diametrically opposed medium, votive images or retablos, religious paintings made on small metal sheets by amateur artists to thank saints for their blessings during a calamity.

[43] The exhibition opening in November was attended by famous figures such as Georgia O'Keeffe and Clare Boothe Luce and received much positive attention in the press, although many critics adopted a condescending tone in their reviews.

[49] She also had several affairs, continuing the one with Nickolas Muray and engaging in ones with Levy and Edgar Kaufmann, Jr.[50] In January 1939, Kahlo sailed to Paris to follow up on André Breton's invitation to stage an exhibition of her work.

[95] Emma Dexter has argued that, as Kahlo derived her mix of fantasy and reality mainly from Aztec mythology and Mexican culture instead of Surrealism, it is more appropriate to consider her paintings as having more in common with magical realism, also known as New Objectivity.

They created large public pieces in the vein of Renaissance masters and Russian socialist realists: they usually depicted masses of people, and their political messages were easy to decipher.

[101] Although she was close to muralists such as Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siquieros and shared their commitment to socialism and Mexican nationalism, the majority of Kahlo's paintings were self-portraits of relatively small size.

[109] According to Schaefer, Kahlo's "mask-like self-portraits echo the contemporaneous fascination with the cinematic close-up of feminine beauty, as well as the mystique of female otherness expressed in film noir.

[111] She also derived inspiration from the works of Hieronymus Bosch, whom she called a "man of genius", and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose focus on peasant life was similar to her own interest in the Mexican people.

[112] Another influence was the poet Rosario Castellanos, whose poems often chronicle a woman's lot in the patriarchal Mexican society, a concern with the female body, and tell stories of immense physical and emotional pain.

[117] Moreover, the picture reflects Kahlo's frustration not only with Rivera, but also her unease with the patriarchal values of Mexico as the scissors symbolize a malevolent sense of masculinity that threatens to "cut up" women, both metaphorically and literally.

[125] For example, when she painted herself following her miscarriage in Detroit in Henry Ford Hospital (1932), she shows herself as weeping, with dishevelled hair and an exposed heart, which are all considered part of the appearance of La Llorona, a woman who murdered her children.

[citation needed] Kahlo often featured her own body in her paintings, presenting it in varying states and disguises: as wounded, broken, as a child, or clothed in different outfits, such as the Tehuana costume, a man's suit, or a European dress.

According to Nancy Cooey, Kahlo made herself through her paintings into "the main character of her own mythology, as a woman, as a Mexican, and as a suffering person ... She knew how to convert each into a symbol or sign capable of expressing the enormous spiritual resistance of humanity and its splendid sexuality".

[149] Her father Guillermo's photography business suffered greatly during the Mexican Revolution, as the overthrown government had commissioned works from him, and the long civil war limited the number of private clients.

[181] The wedding was reported by the Mexican and international press,[182] and the marriage was subject to constant media attention in Mexico in the following years, with articles referring to the couple as simply "Diego and Frida".

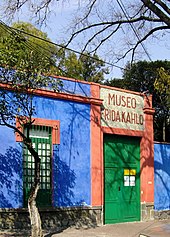

[213] She and Rivera successfully petitioned the Mexican government to grant asylum to former Soviet leader Leon Trotsky and offered La Casa Azul for him and his wife Natalia Sedova as a residence.

[221]Following her separation from Rivera, Kahlo moved back to La Casa Azul and, determined to earn her own living, began another productive period as an artist, inspired by her experiences abroad.

This wild, hybrid Frida, a mixture of tragic bohemian, Virgin of Guadalupe, revolutionary heroine and Salma Hayek, has taken such great hold on the public imagination that it tends to obscure the historically retrievable Kahlo.

[254] Kahlo's reputation as an artist developed late in her life and grew even further posthumously, as during her lifetime she was primarily known as the wife of Diego Rivera and as an eccentric personality among the international cultural elite.

[255] She gradually gained more recognition in the late 1970s when feminist scholars began to question the exclusion of female and non-Western artists from the art historical canon and the Chicano Movement lifted her as one of their icons.

[271] Based on Herrera's biography and starring Salma Hayek (who co-produced the film) as Kahlo, it grossed US$56 million worldwide and earned six Academy Award nominations, winning for Best Makeup and Best Original Score.

[275] According to John Berger, Kahlo's popularity is partly due to the fact that "the sharing of pain is one of the essential preconditions for a refinding of dignity and hope" in twenty-first century society.

[276] Kirk Varnedoe, the former chief curator of MoMA, has stated that Kahlo's posthumous success is linked to the way in which "she clicks with today's sensibilities – her psycho-obsessive concern with herself, her creation of a personal alternative world carries a voltage.

Her constant remaking of her identity, her construction of a theater of the self are exactly what preoccupy such contemporary artists as Cindy Sherman or Kiki Smith and, on a more popular level, Madonna... She fits well with the odd, androgynous hormonal chemistry of our particular epoch.

Even more troubling, though, is that by airbrushing her biography, Kahlo's promoters have set her up for the inevitable fall so typical of women artists, that time when the contrarians will band together and take sport in shooting down her inflated image, and with it, her art.

[281] In the United States, she became the first Hispanic woman to be honored with a U.S. postage stamp in 2001,[282] and was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display in Chicago that celebrates LGBT history and people, in 2012.

[291][292] Additionally, notable artists such as Marina Abramovic,[293] Alana Archer,[294] Gabriela Gonzalez Dellosso,[295] Yasumasa Morimura,[296] Cris Melo,[297] Rupert Garcia,[298] and others have used or appropriated Kahlo's imagery into their own works.