Friends of the Indian

After dealing with "the Indian problem" through treaties, removal, and reservations, the Federal Government of The United States moved toward a method that is now referred to as assimilation.

[1] Since 1787, interactions between Native peoples and the Federal Government have gone through what can be divided into six distinct phases: agreements between equals (1787-1828), removal and reservations (1828-1887), allotment and assimilation (1887-1934), reorganization (1928-1953), termination and relocation (1953-1968), and self-determination (1968–present).

The tactics of assimilation focused on dismantling reservations, making Indigenous people into American citizens, and white-washing Native children.

[6] To help, Christian churches opened mission schools on the reservations to teach the Indigenous children to live like the European-American settlers.

[8] Though experiences differed between boarding schools, most children who attended them were forced to cut their long hair, had their Native clothes exchanged for European-style clothing, were given English names, were discouraged from speaking their native languages, and were trained in skills or vocations that would make them successful in the economy outside of reservations.

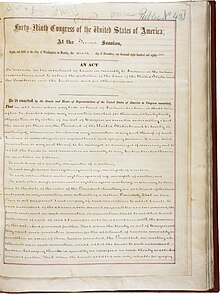

[1] The bill further stated that if Indians proved they could cultivate and improve upon the land they were allotted and denounced tribal allegiances, they would be granted U.S.

[4] This allotment of land was part of the process of assimilation and was done to discourage communalism, a key facet of most Native cultures which the government perceived as uncivilized, and encourage individualism.

[4] The Friends and other advocate groups saw several positives in this legislation: it would break the social unit of Native tribes, encourage more self-reliance and private enterprise, reduce the cost to the Federal Government of administrating over Indians, create more funding for boarding schools, and clear land for white settlement.

[1] As a result of the Dawes Act, 100 million acres of reservation land were transferred from American Indians to white control.

[11] With previous treaties in place, the United States government had to decide if it was going to violate or honor its past agreements and promises.

[1] Dawes argued the case for the bill to the Senate by claiming that labor could lead Natives "out from the darkness and into the light" to "citizenship."

He believed it was the job of the government to prepare Natives for citizenship by teaching them to own and farm land like American citizens.

[7] She assisted in the writing of the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887[7] and seemed to genuinely believe that assimilation was what was best for Native Americans.

[12] Along with having a connection to white policymakers in Washington, D.C., Fletcher was also involved with several reform groups, one of which was the Friends of the Indian.

[14] Reel believed that the Indigenous people were of a "lesser" race which greatly influenced the curriculum taught in the schools.

[1] And though this legislation did grant certain rights and privileges to Native peoples, it came largely at the expense of their autonomy and authority to govern themselves.

The Ojibwe tribe at Red Lake consisted of a majority of warrior people due to continuous warfare in their past.

[3] Sarah Winnemucca, for example, was a Paiute woman who learned how to read and write and adopted European fashion trends.

[4] In a change from previous patterns of legislation being forced on Indians without their consent, each reservation was allowed to vote on whether or not the Reorganization Act would apply to them.

[1] The results of the Act were mixed, with some tribes benefiting from it, and others becoming subject to subtle forms of coercion due to its loopholes.