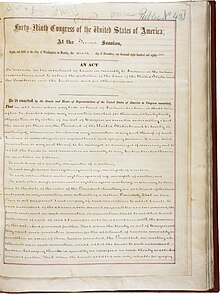

Dawes Act

[3] Before private property could be dispensed, the government had to determine which Indians were eligible for allotments, which propelled an official search for a federal definition of "Indian-ness".

[8] The loss of land ownership and the break-up of traditional leadership of tribes produced potentially negative cultural and social effects that have since prompted some scholars to consider the act as one of the most destructive U.S. policies for Native Americans in history.

[4][3] The "Five Civilized Tribes" (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole) in Indian Territory were initially exempt from the Dawes Act.

During the Great Depression, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration passed the US Indian Reorganization Act (also known as the Wheeler-Howard Law) on June 18, 1934.

During the later nineteenth century, Native American tribes resisted the imposition of the reservation system and engaged with the United States Army (in what were called the Indian Wars in the West) for decades.

[15] The Reservation system, while compulsory for Native Americans, allotted each tribe a claim to their new lands, protection over their territories, and the right to govern themselves.

[18] Senator Henry Dawes launched a campaign to "rid the nation of tribalism through the virtues of private property, allotting land parcels to Indian heads of family.

Responsible for enacting the allotment of the tribal reservations into plots of land for individual households, the Dawes Act was intended by reformers to achieve six goals: The Act facilitated assimilation; they would become more "Americanized" as the government allotted the reservations and the Indians adapted to subsistence farming, the primary model at the time.

[23] The important provisions of the Dawes Act[2] were: Every member of the bands or tribes receiving a land allotment is subject to laws of the state or territory in which they reside.

Every Native American who receives a land allotment "and has adopted the habits of civilized life" (lived separate and apart from the tribe) is bestowed with United States citizenship "without in any manner impairing or otherwise affecting the right of any such Indian to tribal or other property".

The effects of the Dawes Act were destructive on Native American sovereignty, culture, and identity since it empowered the U.S. government to: The federal government initially viewed the Dawes Act as such a successful democratic experiment that they decided to further explore the use of blood-quantum laws and the notion of federal recognition as the qualifying means for "dispensing other resources and services such as health care and educational funding" to Native Americans long after its passage.

Indigenous people labeled "full-blooded" were allocated "relatively small parcels of land deeded with trust patents over which the government retained complete control for a minimum of twenty-five years."

Those who were labeled "mixed-blood" were "deeded larger and better tracts of land, with 'patents in fee simple' (complete control), but were also forced to accept U.S. citizenship and relinquish tribal status.

"[35] The Dawes Act ended Native American communal holding of property (with cropland often being privately owned by families or clans[36]), by which they had ensured that everyone had a home and a place in the tribe.

The act "was the culmination of American attempts to destroy tribes and their governments and to open Indian lands to settlement by non-Indians and to development by railroads.

In an attempt to fulfill this objective, the Dawes Act "outlawed Native American culture and established a code of Indian offenses regulating individual behavior according to Euro-American norms of conduct."

Included with the Dawes Act were "funds to instruct Native Americans in Euro-American patterns of thought and behavior through Indian Service schools.

"[5] With the seizure of many Native American land holdings, indigenous structures of domestic life, gender roles, and tribal identity were critically altered in order to meld with society.

As a result, "in evolutionary terms, Whites saw women's performance of what seemed to be male tasks – farming, home building, and supply gathering – as a corruption of gender roles and an impediment to progress."

Although private property ownership was the cornerstone of the act, reformers "believed that civilization could only be effected by concomitant changes to social life" in indigenous communities.

As a result, "they promoted Christian marriages among indigenous people, forced families to regroup under male heads (a tactic often enforced by renaming), and trained men in wage-earning occupations while encouraging women to support them at home through domestic activities.

[45] The act reads: ... the Secretary of the Interior may, in his discretion, and he is hereby authorized, whenever he shall be satisfied that any Native American allottee is competent and capable of managing his or her affairs at any time to cause to be issued to such allottee a patent in fee simple, and thereafter all restrictions as to sale, encumbrance, or taxation of said land shall be removed.The use of competence opens up the categorization, making it much more subjective and thus increasing the exclusionary power of the Secretary of Interior.

[46] In 1926, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work commissioned a study of the federal administration of Indian policy and the condition of Native American people.

For example, one provision of the Act was the establishment of a trust fund, administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to collect and distribute revenues from oil, mineral, timber, and grazing leases on Native American lands.

The BIA's alleged improper management of the trust fund resulted in litigation, in particular the case Cobell v. Kempthorne (settled in 2009 for $3.4 billion), to force a proper accounting of revenues.

[citation needed] Interior is involved in "the management of 100,000 leases for individual [Native Americans] and tribes on trust land that encompasses approximately 56,000,000 acres (230,000 km2).

As a result, the usual incentives found in the commercial sector for reducing the number of small or inactive accounts do not apply to the Indian trust.

Because of opposition to many of these provisions in Indian Country, often by the major European-American ranchers and industry who leased land and other private interests, most were removed while Congress was considering the bill.

Although Congress enabled major reforms in the structure of tribes through the IRA and stopped the allotment process, it did not meaningfully address fractionation as had been envisioned by John Collier, then Commissioner of Indian Affairs, or the Brookings Institution.

[51] Ellen Fitzpatrick claimed that Debo's book "advanced a crushing analysis of the corruption, moral depravity, and criminal activity that underlay White administration and execution of the allotment policy.