Frog

See text A frog is any member of a diverse and largely carnivorous group of short-bodied, tailless amphibians composing the order Anura[1] (coming from the Ancient Greek ἀνούρα, literally 'without tail').

Their skin varies in colour from well-camouflaged dappled brown, grey and green to vivid patterns of bright red or yellow and black to show toxicity and ward off predators.

Frogs produce a wide range of vocalisations, particularly in their breeding season, and exhibit many different kinds of complex behaviors to attract mates, to fend off predators and to generally survive.

[13] The third edition of the Oxford English Dictionary finds that the etymology of *froskaz is uncertain, but agrees with arguments that it could plausibly derive from a Proto-Indo-European base along the lines of *preu, meaning 'jump'.

The characteristics of anuran adults include: 9 or fewer presacral vertebrae, the presence of a urostyle formed of fused vertebrae, no tail, a long and forward-sloping ilium, shorter fore limbs than hind limbs, radius and ulna fused, tibia and fibula fused, elongated ankle bones, absence of a prefrontal bone, presence of a hyoid plate, a lower jaw without teeth (with the exception of Gastrotheca guentheri) consisting of three pairs of bones (angulosplenial, dentary, and mentomeckelian, with the last pair being absent in Pipoidea),[18] an unsupported tongue, lymph spaces underneath the skin, and a muscle, the protractor lentis, attached to the lens of the eye.

[30] Salientia (Latin salire (salio), "to jump") is the name of the total group that includes modern frogs in the order Anura as well as their close fossil relatives, the "proto-frogs" or "stem-frogs".

The common features possessed by these proto-frogs include 14 presacral vertebrae (modern frogs have eight or 9), a long and forward-sloping ilium in the pelvis, the presence of a frontoparietal bone, and a lower jaw without teeth.

[38] According to genetic studies, the families Hyloidea, Microhylidae, and the clade Natatanura (comprising about 88% of living frogs) diversified simultaneously some 66 million years ago, soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event associated with the Chicxulub impactor.

[46] Leiopelmatidae Ascaphidae Bombinatoridae Alytidae Discoglossidae Pipidae Rhinophrynidae Scaphiopodidae Pelodytidae Pelobatidae Megophryidae Heleophrynidae Sooglossidae Nasikabatrachidae Calyptocephalellidae Myobatrachidae Limnodynastidae Ceuthomantidae Brachycephalidae Eleutherodactylidae Craugastoridae Hemiphractidae Hylidae Bufonidae Aromobatidae Dendrobatidae Leptodactylidae Allophrynidae Centrolenidae Ceratophryidae Odontophrynidae Cycloramphidae Alsodidae Hylodidae Telmatobiidae Batrachylidae Rhinodermatidae Microhylidae Brevicipitidae Hemisotidae Hyperoliidae Arthroleptidae Ptychadenidae Micrixalidae Phrynobatrachidae Conrauidae Petropedetidae Pyxicephalidae Nyctibatrachidae Ceratobatrachidae Ranixalidae Dicroglossidae Rhacophoridae Mantellidae Ranidae Frogs have no tail, except as larvae, and most have long hind legs, elongated ankle bones, webbed toes, no claws, large eyes, and a smooth or warty skin.

Occasionally, a parasitic flatworm (Ribeiroia ondatrae) digs into the rear of a tadpole, causing a rearrangement of the limb bud cells and the frog develops one or more extra legs.

[54] The African bullfrog (Pyxicephalus), which preys on relatively large animals such as mice and other frogs, has cone shaped bony projections called odontoid processes at the front of the lower jaw which function like teeth.

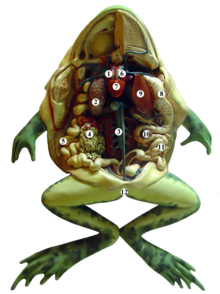

Pancreatic juice from the pancreas, and bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, are secreted into the small intestine, where the fluids digest the food and the nutrients are absorbed.

Aquatic species such as the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) normally sink to the bottom of the pond where they lie, semi-immersed in mud but still able to access the oxygen dissolved in the water.

[100] At the other extreme, the striped burrowing frog (Cyclorana alboguttata) regularly aestivates during the hot, dry season in Australia, surviving in a dormant state without access to food and water for nine or ten months of the year.

The Plains spadefoot toad (Spea bombifrons) is typical and has a flap of keratinised bone attached to one of the metatarsals of the hind feet which it uses to dig itself backwards into the ground.

[119] Spadefoot toads are "explosive breeders", all emerging from their burrows at the same time and converging on temporary pools, attracted to one of these by the calling of the first male to find a suitable breeding location.

One of these, the green burrowing frog (Scaphiophryne marmorata), has a flattened head with a short snout and well-developed metatarsal tubercles on its hind feet to help with excavation.

The surface of the toe pads is formed from a closely packed layer of flat-topped, hexagonal epidermal cells separated by grooves into which glands secrete mucus.

[130] Some female New Mexico spadefoot toads (Spea multiplicata) only spawn half of the available eggs at a time, perhaps retaining some in case a better reproductive opportunity arises later.

This has been suggested as an adaptation to their lifestyles; because the transformation into frogs happens very fast, the tail is made of soft tissue only, as bone and cartilage take a much longer time to be broken down and absorbed.

[160][161] A few species also eat plant matter; the tree frog Xenohyla truncata is partly herbivorous, its diet including a large proportion of fruit, floral structures and nectar.

The northern leopard frog (Rana pipiens) is eaten by herons, hawks, fish, large salamanders, snakes, raccoons, skunks, mink, bullfrogs, and other animals.

Using this method, the ages of mountain yellow-legged frogs (Rana muscosa) were studied, the phalanges of the toes showing seasonal lines where growth slows in winter.

Certain frog species avoid this competition by making use of smaller phytotelmata (water-filled leaf axils or small woody cavities) as sites for depositing a few tadpoles.

[196][197] Many species are isolated in restricted ranges by changes of climate or inhospitable territory, such as stretches of sea, mountain ridges, deserts, forest clearance, road construction, or other human-made barriers.

[203] Elsewhere, habitat loss is a significant cause of frog population decline, as are pollutants, climate change, increased UVB radiation, and the introduction of non-native predators and competitors.

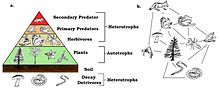

[206][207] Many environmental scientists believe amphibians, including frogs, are good biological indicators of broader ecosystem health because of their intermediate positions in food chains, their permeable skins, and typically biphasic lives (aquatic larvae and terrestrial adults).

Various causes have been identified or hypothesized, including an increase in ultraviolet radiation affecting the spawn on the surface of ponds, chemical contamination from pesticides and fertilizers, and parasites such as the trematode Ribeiroia ondatrae.

A sample of urine from a pregnant woman injected into a female frog induces it to lay eggs, a discovery made by English zoologist Lancelot Hogben.

Although alternative pregnancy tests have been developed, biologists continue to use Xenopus as a model organism in developmental biology because their embryos are large and easy to manipulate, they are readily obtainable, and can easily be kept in the laboratory.

( Rana temporaria )

( Rana clamitans )