Megabat

The leading theory of the evolution of megabats has been determined primarily by genetic data, as the fossil record for this family is the most fragmented of all bats.

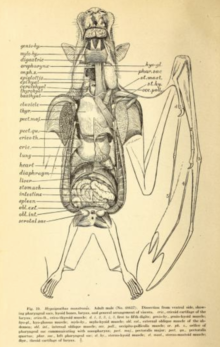

Megabats have several adaptations for flight, including rapid oxygen consumption, the ability to sustain heart rates of more than 700 beats per minute, and large lung volumes.

Pteropodinae Nyctimeninae Cynopterinae Eidolinae Scotonycterini Eonycterini Rousettini Stenonycterini Plerotini Myonycterini Epomophorini The family Pteropodidae was first described in 1821 by British zoologist John Edward Gray.

[7]: 230 In 1875, the zoologist George Edward Dobson was the first to split the order Chiroptera (bats) into two suborders: Megachiroptera (sometimes listed as Macrochiroptera) and Microchiroptera, which are commonly abbreviated to megabats and microbats.

[15]: 496 A 1995 study found that Macroglossinae as previously defined, containing the genera Eonycteris, Notopteris, Macroglossus, Syconycteris, Melonycteris, and Megaloglossus, was paraphyletic, meaning that the subfamily did not group all the descendants of a common ancestor.

[2] In 1984, an additional pteropodid subfamily, Propottininae, was proposed, representing one extinct species described from a fossil discovered in Africa, Propotto leakeyi.

Pteropodidae split from the superfamily Rhinolophoidea (which contains all the other families of the suborder Yinpterochiroptera) approximately 58 Mya (million years ago).

The four proposed events are represented by (1) Scotonycteris, (2) Rousettus, (3) Scotonycterini, and (4) the "endemic Africa clade", which includes Stenonycterini, Plerotini, Myonycterini, and Epomophorini, according to a 2016 study.

It is unknown when megabats reached Africa, but several tribes (Scotonycterini, Stenonycterini, Plerotini, Myonycterini, and Epomophorini) were present by the Late Miocene.

The genus Pteropus (flying foxes), which is not found on mainland Africa, is proposed to have dispersed from Melanesia via island hopping across the Indian Ocean;[27] this is less likely for other megabat genera, which have smaller body sizes and thus have more limited flight capabilities.

The primitive insertion of the omohyoid muscle from the clavicle (collarbone) to the scapula is laterally displaced (more towards the side of the body)—a feature also seen in the Phyllostomidae.

[60] The length of the digestive system is short for a herbivore (as well as shorter than those of insectivorous microchiropterans),[60] as the fibrous content is mostly separated by the action of the palate, tongue, and teeth, and then discarded.

[55] Relative to their sizes, megabats have low reproductive outputs and delayed sexual maturity, with females of most species not giving birth until the age of one or two.

[74] The post-implantation delay means that development of the embryo is suspended for up to eight months after implantation in the uterine wall, which is responsible for its very long pregnancies.

Megabats will vocalize to communicate with each other, creating noises described as "trill-like bursts of sound",[85] honking,[86] or loud, bleat-like calls[87] in various genera.

[41] Other food resources include leaves, shoots, buds, pollen, seed pods, sap, cones, bark, and twigs.

Migratory species of the genera Eidolon, Pteropus, Epomophorus, Rousettus, Myonycteris, and Nanonycteris can migrate distances up to 750 km (470 mi).

As a result of their long evolutionary history, some plants have evolved characteristics compatible with bat senses, including fruits that are strongly scented, brightly colored, and prominently exposed away from foliage.

[105] Predators that are naturally sympatric with megabats include reptiles such as crocodilians, snakes, and large lizards, as well as birds like falcons, hawks, and owls.

[106] During extreme heat events, megabats like the little red flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus) must cool off and rehydrate by drinking from waterways, making them susceptible to opportunistic depredation by freshwater crocodiles.

[41][111] Megabats are widely distributed in the tropics of the Old World, occurring throughout Africa, Asia, Australia, and throughout the islands of the Indian Ocean and Oceania.

In China, only six species of megabat are considered resident, while another seven are present marginally (at the edge of their ranges), questionably (due to possible misidentification), or as accidental migrants.

Bats are consumed extensively throughout Asia, as well as in islands of the West Indian Ocean and the Pacific, where Pteropus species are heavily hunted.

In continental Africa where no Pteropus species live, the straw-colored fruit bat, the region's largest megabat, is a preferred hunting target.

[124] In Guam, consumption of the Mariana fruit bat exposes locals to the neurotoxin beta-Methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) which may later lead to neurodegenerative diseases.

[128][129] The virus was first recognized after simultaneous outbreaks in the German cities of Marburg and Frankfurt as well as Belgrade, Serbia, in 1967,[129] where 31 people became ill and seven died.

Habitat loss and resulting urbanization leads to construction of new roadways, making megabat colonies easier to access for overharvesting.

Additionally, habitat loss via deforestation compounds natural threats, as fragmented forests are more susceptible to damage from typhoon-force winds.

Food resources for the bats become scarce after major storms, and megabats resort to riskier foraging strategies such as consuming fallen fruit off the ground.

Flying foxes, including the endangered Mariana fruit bat,[119][162] have been nearly exterminated from the island of Anatahan following a series of eruptions beginning in 2003.