Marburg virus

[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) rates it as a Risk Group 4 Pathogen (requiring biosafety level 4-equivalent containment).

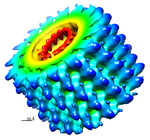

At the center is the helical ribonucleocapsid, which consists of the genomic RNA wrapped around a polymer of nucleoproteins (NP).

Two independent studies reported in the same issue of Nature showed that Ebola virus cell entry and replication requires NPC1.

[22][24] In the other study, mice that were heterozygous for NPC1 were shown to be protected from lethal challenge with mouse-adapted Ebola virus.

[citation needed] The virus RdRp partially uncoats the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-stranded mRNAs, which are then translated into structural and nonstructural proteins.

[25] The most abundant protein produced is the nucleoprotein, whose concentration in the cell determines when L switches from gene transcription to genome replication.

Replication results in full-length, positive-stranded antigenomes that are in turn transcribed into negative-stranded virus progeny genome copies.

Newly synthesized structural proteins and genomes self-assemble and accumulate near the inside of the cell membrane.

[14] In 2009, the successful isolation of infectious MARV was reported from caught healthy Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus).

The Marburg strains had a mean root time of the most recent common ancestor of 177.9 years ago (95% highest posterior density 87–284) suggesting an origin in the mid 19th century.

In contrast, the Ravn strains origin dated back to a mean 33.8 years ago (the early 1980s).

[74] Several animal models have shown to be effective in the research of Marburg virus, such as hamsters, mice, and non-human primates (NHPs).

Mice are useful in the initial phases of vaccine development as they are ample models for mammalian disease, but their immune systems are still different enough from humans to warrant trials with other mammals.

Virus replicon particles (VRPs) were shown to be effective in guinea pigs, but lost efficacy once tested on NHPs.

It was developed alongside vaccines for closely-related Ebolaviruses by the Canadian government in the early 2000s, twenty years before the outbreak.

[79][80][81][82] As of June 23, 2022, researchers working with the Public Health Agency of Canada conducted a study which showed promising results of a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV) vaccine in guinea pigs, entitled PHV01.

According to the study, inoculation with the vaccine approximately one month prior to infection with the virus provided a high level of protection.

Human vaccination trials are either ultimately unsuccessful or are missing data specifically regarding Marburg virus.

However, Soviet defector Ken Alibek claimed that a weapon filled with MARV was tested at the Stepnogorsk Scientific Experimental and Production Base in Stepnogorsk, Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (today Kazakhstan),[86] suggesting that the development of a MARV biological weapon had reached advanced stages.

At least one laboratory accident with MARV, resulting in the death of Koltsovo researcher Nikolai Ustinov, occurred during the Cold War in the Soviet Union and was first described in detail by Alibek.