Fundamental group

It describes the monodromy properties of complex-valued functions, as well as providing a complete topological classification of closed surfaces.

The idea of the definition of the homotopy group is to measure how many (broadly speaking) curves on X can be deformed into each other.

It can be shown that this product does not depend on the choice of representatives and therefore gives a well-defined operation on the set

The associativity axiom therefore crucially depends on the fact that paths are considered up to homotopy.

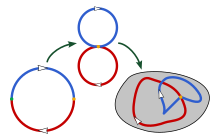

The fundamental group of a wedge sum of two path connected spaces X and Y can be computed as the free product of the individual fundamental groups: This generalizes the above observations since the figure eight is the wedge sum of two circles.

In particular, consider a connected graph G = (V, E), with a designated vertex v0 in V. The loops in G are the cycles that start and end at v0.

However, the Eckmann–Hilton argument shows that it does in fact agree with the above concatenation of loops, and moreover that the resulting group structure is abelian.

Related ideas lead to Heinz Hopf's computation of the cohomology of a Lie group.

It turns out that this functor does not distinguish maps that are homotopic relative to the base point: if

As a consequence, two homotopy equivalent path-connected spaces have isomorphic fundamental groups: For example, the inclusion of the circle in the punctured plane is a homotopy equivalence and therefore yields an isomorphism of their fundamental groups.

A special case of the Hurewicz theorem asserts that the first singular homology group

This difference is, however, the only one: if X is path-connected, this homomorphism is surjective and its kernel is the commutator subgroup of the fundamental group, so that

can be obtained by gluing two copies of slightly overlapping half-spheres along a neighborhood of the equator.

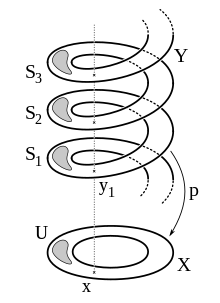

[11] Given a topological space B, a continuous map is called a covering or E is called a covering space of B if every point b in B admits an open neighborhood U such that there is a homeomorphism between the preimage of U and a disjoint union of copies of U (indexed by some set I), in such a way that

For example, the uniformization theorem shows that any simply connected Riemann surface is (isomorphic to) either

The great importance of fibrations to the computation of homotopy groups stems from a long exact sequence provided that B is path-connected.

If E happens to be path-connected and simply connected, this sequence reduces to an isomorphism which generalizes the above fact about the universal covering (which amounts to the case where the fiber F is also discrete).

The map can be shown to be surjective[21] with kernel given by the set I of integer linear combination of coroots.

This leads to the computation This method shows, for example, that any connected compact Lie group for which the associated root system is of type

When the topological space is homeomorphic to a simplicial complex, its fundamental group can be described explicitly in terms of generators and relations.

If T is a maximal spanning tree in the 1-skeleton of X, then E(X, v) is canonically isomorphic to the group with generators (the oriented edge-paths of X not occurring in T) and relations (the edge-equivalences corresponding to triangles in X).

The points (w,γ) and (u, γu) are the vertices of the "transported" simplex in the universal covering space.

The edge-path group acts naturally by concatenation, preserving the simplicial structure, and the quotient space is just X.

This was doubtless known to Eduard Čech and Jean Leray and explicitly appeared as a remark in a paper by André Weil;[25] various other authors such as Lorenzo Calabi, Wu Wen-tsün, and Nodar Berikashvili have also published proofs.

Since the length r is variable in this approach, such paths can be concatenated as is (i.e., not up to homotopy) and therefore yield a category.

It reproduces the fundamental group since More generally, one can consider the fundamental groupoid on a set A of base points, chosen according to the geometry of the situation; for example, in the case of the circle, which can be represented as the union of two connected open sets whose intersection has two components, one can choose one base point in each component.

[32] Generally speaking, representations may serve to exhibit features of a group by its actions on other mathematical objects, often vector spaces.

Representations of the fundamental group have a very geometric significance: any local system (i.e., a sheaf

on X with the property that locally in a sufficiently small neighborhood U of any point on X, the restriction of F is a constant sheaf of the form

This yields a theory applicable in situations where no great generality classical topological intuition whatsoever is available, for example for varieties defined over a finite field.

![{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} \times [0,1]\to S^{1}\times [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/55229ba769397f519a90364e5ce40f6d24db1cea)

![{\displaystyle \mathbb {R} \times [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c3285b58a0be50e3b4926bac33a1b2374d76979b)