Funeral march

Among the Romans, the traditional funeral (funus translaticium) involved the presence of musicians at the opening of the procession: two cornicini, four tibicini and a lituus, a special trumpet with a soft sound that was well suited to the circumstances.

[5] The eighteenth century was relatively scarce with funeral marches, both in military repertoires and in the works of great composers, but it still produced notable examples and, above all, freed the genre from its ceremonial function.

[2] The lacerating Lugubrious March composed by Francois-Joseph Gossec to celebrate the victims of an anti-royalist uprising on 20 September 1790 known as the Nancy affair which marked a decisive turning point.

Performed on the Champ de Mars in memory of the fallen soldiers, it aroused great emotion and sets the standard for the nineteenth-century funeral march.

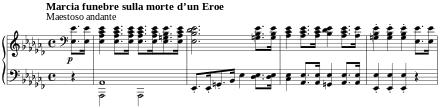

But what is of greatest importance is the second movement of the Eroica (1802-1804) which, in addition to innovating the very way of conceiving the central slow tempo of the symphony form, definitively frees the funeral march from functionality to practical use, drawing from it a pure concert piece.

The funeral march that opens the finale of the second act in Rossini's Gazza ladra (1819) (Infelice, unfortunate) is renowned throughout the nineteenth century and heralds a new turning point in the evolution of the genre, introducing a previously unknown melodic lyricism.

[clarification needed] In addition to the works of Beethoven and Rossini, the Polish composer almost certainly knew the first movement of Berlioz's Great Funeral and Triumphal Symphony before its official debut in 1840, but it possesses a very different character and in all likelihood represents a model negative.

In Chopin's funeral march, the central section in a major mode trio presents a theme that is not only complete, but that can be counted among the melodic peaks reached by the author in all of his production.

[14] Compared to Beethoven, the heroic and glorious dimension has been completely lost: the Chopin trio rather expresses a defeat, for some a prayer, for others only profound sadness, in a humanization of death which has certainly contributed to the popularity of the song.

It is a difficult passage to interpret, not surprisingly criticized and even repudiated as "abominable" by Bülow, or instead considered a "touchstone" of the pianist 's sensitivity such as Wilhelm von Lenz.

[16] Towards the end of the century, the funeral march played an important symbolic role in Gustav Mahler's production, starting with the romance Die zwei blauen Augen (1884) taken from the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen.

[17] In the second volume of the collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn, which had a great influence on the first four symphonies and which stood out for the extreme nature of the emotions addressed, the echo of Die zwei blauen Augen stands out, melodically recalled by Nicht wiedersehen!

The fundamental quote is a gloomy parody of the Fra Martino canon, a childish song to which Mahler has always attributed a sense of tragedy, which obsesses him all the time just as he is looking for an incipit and which, finally accepted into the symphony, sustains a sarcastic and sinister atmosphere.

The first finds its precedent in the parodic funeral march of A Midsummer Night's Dream (1843), a short-lived piece which in turn hints at Fra Martino 's theme and furthermore retains the typical trait of dotted rhythm.

In the archives of the Hermandad de la Amargura (Brotherhood of Bitterness) of Seville, there is evidence of the Lenten funeral marches with the formation of the musical band known as the Banda del Asilo de San Fernando and today as the Municipal Symphonic Band of Seville through the artistic activity of Andrés Palatín Palma, who provided musical services for Holy Week since April 14, 1838.

[19] In Italy, the earliest record of a special repertoire for those bands dates from 1857, the year in which Vincenzo Valente (1830-1908) composed U Conzasiegge, the oldest Molfetta Funeral March known today.

Since the 1870s, this melody has accompanied the journey of the Virgin of Sorrows, one of the most revered Catholic images of Arequipa, whose procession takes place every Good Friday of Holy Week, from the church of Santo Domingo.

[22] In particular, the funeral marches stand out in the production of Shostakovich, whose entire work is permeated by death, of which he is a constant witness in the collective tragedies of Russian history of the 20th century.

The composer made his debut in the genre at the age of eleven with a piano piece dedicated to the fallen of the October Revolution (1917), transcribed a work by Schubert (1920) and then left numerous other examples, including the adagio In memoriam of the Symphony no.

Thus, during Holy Week in Leon in 1959, a great novelty occurs: for the first time, a band of bugles and drums belonging entirely to a brotherhood and parades in a tunic accompanying the images of the Passion, Death and Resurrection of Our Lord.

The mutual enrichment and recognition between classical and popular "band" funeral marches was reached with this composition which go "in crescendo" until the explosion of the final tutti, allowing it to share programs with the "Passion" Symphony by J. Haydn and the Requiem by W. A. Mozart.

Mendelssohn, who for the fifth volume of hisSongs without Words composed a piece which overall did not correspond to the form of the funeral march, had his publishers title it Trauermarsch simply because of the characteristics of the first bars.

It is possible that the influences of national military traditions weighed on the choice of composers: the Austrian one, for example, prescribed the more pressing pace typical of the marches of the grenadiers and riflemen.

[11] The military manuals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries do not expressly set the funeral march tempo, but suggest that it is at most that of the ordinary pace, and if possible slower.

This section can represent a pitiful episode, or a consolatory one, or a heroic one, or at times (as in the specific case of Chopin's masterpiece) of complex interpretation, or it may want to sublimate death into a positive mystery.

Funeral marches found their most common and regular expression in the Passiontide processions of the Spanish and Italian religious tradition which were propagated to Latin America especially Peru and Guatemala and all of Christianity.

In southern Italy, popular funeral marches are still enormous successful, and musical bands perform entire repertoires of them in the long demonstrations of Holy Week.

[32] The unmistakability of its characteristics and the possibility of exploiting its stereotypes makes the funeral march a genre that lends itself well to parodic and joking use, to the point of the grotesque.

[33] The French humorist Alphonse Allais "wrote" a Marche funèbre composée pour les funérailles d'un grand homme sourd, a completely blank score bearing the time signature Lento rigolando (inspired by the colloquial verb rigoler, "to joke").

[32] When they play funeral marchs, film soundtracks often draw on the classical repertoire (with a clear prevalence of the two famous works by Chopin and Gounod), but sometimes they also use original pieces.