Fusion power

Classified programs began in the 1950s on magnetic confinement fusion devices, with US and UK investigating theta-pinch, z-pinch, and stellarator designs, demonstrating the first reactions in Los Alamos' Scylla in 1958.

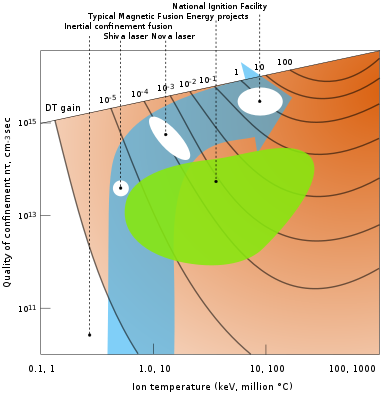

It received major investment following the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, including the National Ignition Facility, which has made positive fusion gain breakthroughs since 2022.

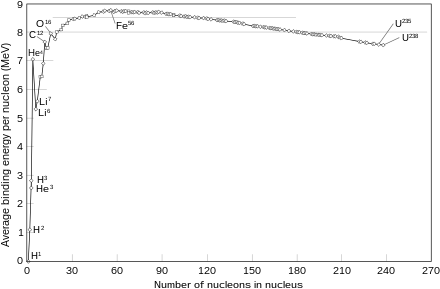

The repulsive electrostatic interaction between nuclei operates across larger distances than the strong force, which has a range of roughly one femtometer—the diameter of a proton or neutron.

The fuel atoms must be supplied enough kinetic energy to approach one another closely enough for the strong force to overcome the electrostatic repulsion in order to initiate fusion.

[10] Conduction occurs when ions, electrons, or neutrals impact other substances, typically a surface of the device, and transfer a portion of their kinetic energy to the other atoms.

[citation needed] In 2014, Google began working with California-based fusion company TAE Technologies to control the Joint European Torus (JET) to predict plasma behavior.

In addition, the power density is 2500 times lower than for D-T, although per unit mass of fuel, this is still considerably higher compared to fission reactors.

For this reason, many fusion companies that rely on magnetic fields to control their plasma are trying to develop high temperature superconducting devices.

Alpha particles, once stabilized by capturing electrons, form helium atoms which accumulate at grain boundaries and may result in swelling, blistering, or embrittlement of the material.

[109][110] Tungsten is widely regarded as the optimal material for plasma-facing components in next-generation fusion devices due to its unique properties and potential for enhancements.

Its low sputtering rates and high melting point make it particularly suitable for the high-stress environments of fusion reactors, allowing it to withstand intense conditions without rapid degradation.

Additionally, tungsten's low tritium retention through co-deposition and implantation is essential in fusion contexts, as it helps to minimize the accumulation of this radioactive isotope.

Tritium retention in silicon carbide plasma-facing components is approximately 1.5-2 times higher than in graphite, resulting in reduced fuel efficiency and heightened safety risks in fusion reactors.

[116][117] Furthermore, the chemical and physical sputtering of SiC remains significant, contributing to tritium buildup through co-deposition over time and with increasing particle fluence.

Lattice strain induced by the He bubbles cause Si atoms to diffuse out of compressive areas, typically towards the surface of the material, forming a protective silicon dioxide layer.

This localized congregation around iron silicate nanoparticles induces matrix strain rather than weakening grain boundaries, preserving the material’s strength and longevity.

If a large magnet undergoes a quench, the inert vapor formed by the evaporating cryogenic fluid can present a significant asphyxiation hazard to operators by displacing breathable air.

Further, the material it creates is less damaging biologically, and the radioactivity dissipates within a time period that is well within existing engineering capabilities for safe long-term waste storage.

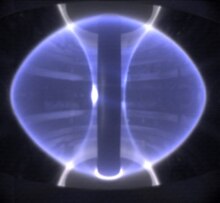

[162] Tokamak designs appear to be labour-intensive,[163] while the commercialization risk of alternatives like inertial fusion energy is high due to the lack of government resources.

[164] Scenarios since 2010 note computing and material science advances enabling multi-phase national or cost-sharing "Fusion Pilot Plants" (FPPs) along various technology pathways,[165][159][166][167][168][169] such as the UK Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production, within the 2030–2040 time frame.

[174] In the United States, cost-sharing public-private partnership FPPs appear likely,[175] and in 2022 the DOE announced a new Milestone-Based Fusion Development Program as the centerpiece of its Bold Decadal Vision for Commercial Fusion Energy,[176] which envisages private sector-led teams delivering FPP pre-conceptual designs, defining technology roadmaps, and pursuing the R&D necessary to resolve critical-path scientific and technical issues towards an FPP design.

[180] In some applications, fusion power could provide the base load, especially if including integrated thermal storage and cogeneration and considering the potential for retrofitting coal plants.

The following month, the United States Department of Energy, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the Fusion Industry Association co-hosted a public forum to begin the process.

[152] In November 2020, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) began working with various nations to create safety standards[188] such as dose regulations and radioactive waste handling.

[189][190] A public-private cost-sharing approach was endorsed in the 27 December H.R.133 Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, which authorized $325 million over five years for a partnership program to build fusion demonstration facilities, with a 100% match from private industry.

[203][131] However, technological developments[204] and private sector involvement has raised concerns over intellectual property, regulatory administration, global leadership;[201] equity, and potential weaponization.

[267] In October, researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Plasma Physics in Greifswald, Germany, completed building the largest stellarator to date, the Wendelstein 7-X (W7-X).

[283] In November 2021, Helion Energy reported receiving $500 million in Series E funding for its seventh-generation Polaris device, designed to demonstrate net electricity production, with an additional $1.7 billion of commitments tied to specific milestones,[286] while Commonwealth Fusion Systems raised an additional $1.8 billion in Series B funding to construct and operate its SPARC tokamak, the single largest investment in any private fusion company.

The granted companies are tasked with addressing the scientific and technical challenges to create viable fusion pilot plant designs in the next 5–10 years.

[292] Subsequently, South Korea's fusion reactor project, the Korean Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research, successfully operated for 102 seconds in a high-containment mode (H-mode) containing high ion temperatures of more than 100 million degrees in plasma tests conducted from December 2023 to February 2024.