Nuclear fission

The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactive decay.

Hahn and Strassmann proved that a fission reaction had taken place on 19 December 1938, and Meitner and her nephew Frisch explained it theoretically in January 1939.

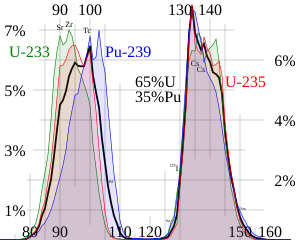

The two (or more) nuclei produced are most often of comparable but slightly different sizes, typically with a mass ratio of products of about 3 to 2, for common fissile isotopes.

The thorium fuel cycle produces virtually no plutonium and much less minor actinides, but 232U - or rather its decay products - are a major gamma ray emitter.

Though less common than binary fission, it still produces significant helium-4 and tritium gas buildup in the fuel rods of modern nuclear reactors.

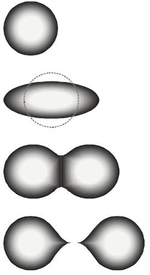

The stimulation of the nucleus after neutron bombardment was analogous to the vibrations of a liquid drop, with surface tension and the Coulomb force in opposition.

Fissionable isotopes such as uranium-238 require additional energy provided by fast neutrons (such as those produced by nuclear fusion in thermonuclear weapons).

In this case, the first experimental atomic reactors would have run away to a dangerous and messy "prompt critical reaction" before their operators could have manually shut them down (for this reason, designer Enrico Fermi included radiation-counter-triggered control rods, suspended by electromagnets, which could automatically drop into the center of Chicago Pile-1).

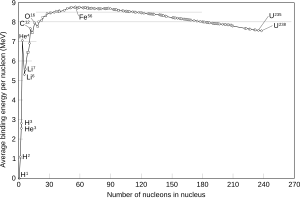

Additional terms can be included such as symmetry, pairing, the finite range of the nuclear force, and charge distribution within the nuclei to improve the estimate.

It is much less than the prompt energy, but it is a significant amount and is why reactors must continue to be cooled after they have been shut down and why the waste products must be handled with great care and stored safely.

It is possible to achieve criticality in a reactor using natural uranium as fuel, provided that the neutrons have been efficiently moderated to thermal energies."

[22]: 1–4 The objective of an atomic bomb is to produce a device, according to Serber, "...in which energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission."

According to Rhodes, "Untamped, a bomb core even as large as twice the critical mass would completely fission less than 1 percent of its nuclear material before it expanded enough to stop the chain reaction from proceeding.

However, any bomb would "necessitate locating, mining and processing hundreds of tons of uranium ore...", while U-235 separation or the production of Pu-239 would require additional industrial capacity.

The German chemist Ida Noddack notably suggested in 1934 that instead of creating a new, heavier element 93, that "it is conceivable that the nucleus breaks up into several large fragments.

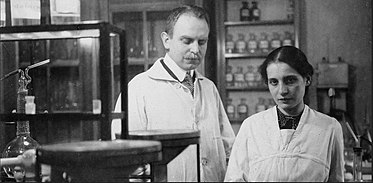

[35] After the Fermi publication, Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann began performing similar experiments in Berlin.

By coincidence, her nephew Otto Robert Frisch, also a refugee, was also in Sweden when Meitner received a letter from Hahn dated 19 December describing his chemical proof that some of the product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons was barium.

Meitner's and Frisch's interpretation of the discovery of Hahn and Strassmann crossed the Atlantic Ocean with Niels Bohr, who was to lecture at Princeton University.

On 25 January 1939, a Columbia University team conducted the first nuclear fission experiment in the United States,[40] which was done in the basement of Pupin Hall.

The experiment involved placing uranium oxide inside of an ionization chamber and irradiating it with neutrons, and measuring the energy thus released.

[42] The 11 February 1939 paper by Meitner and Frisch compared the process to the division of a liquid drop and estimated the energy released at 200 MeV.

[44][5]: 262, 311 [4]: 9–13 During this period the Hungarian physicist Leó Szilárd realized that the neutron-driven fission of heavy atoms could be used to create a nuclear chain reaction.

On 25 January 1939, after learning of Hahn's discovery from Eugene Wigner, Szilard noted, "...if enough neutrons are emitted...then it should be, of course, possible to sustain a chain reaction.

[5]: 291, 298–302 In August 1939, Szilard, Teller and Wigner thought that the Germans might make use of the fission chain reaction and were spurred to attempt to attract the attention of the United States government to the issue.

[5]: 303–309, 312–317 In February 1940, encouraged by Fermi and John R. Dunning, Alfred O. C. Nier was able to separate U-235 and U-238 from uranium tetrachloride in a glass mass spectrometer.

[5]: 381, 387–388 On 23 April 1942, Met Lab scientists discussed seven possible ways to extract plutonium from irradiated uranium, and decided to pursue investigation of all seven.

On 17 June, the first batch of uranium nitrate hexahydrate (UNH) was undergoing neutron bombardment in the Washington University in St. Louis cyclotron.

Packed into fifty-two cans two inches in diameter and two feet long in a tank of manganese solution, they were able to confirm more neutrons were emitted than absorbed.

Finally, acquiring pure uranium metal from the Ames process, meant the replacement of oxide pseudospheres with Frank Spedding's "eggs".

Starting on 16 November 1942, Fermi had Anderson and Zinn working in two twelve-hours shifts, constructing a pile that eventually reached 57 layers by 1 Dec.