Fyodor Dostoevsky

[4][5] Dostoevsky's literary works explore the human condition in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes.

His writings were widely read both within and beyond his native Russia and influenced an equally great number of later writers including Russians such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Anton Chekhov, philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre, and the emergence of Existentialism and Freudianism.

The family traced its roots back to Danilo Irtishch, who was granted lands in the Pinsk region (for centuries part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, now in modern-day Belarus) in 1509 for his services under a local prince, his progeny then taking the name "Dostoevsky" based on a village there called Dostojewo [pl] (derived from Old Polish dostojnik – dignitary).

In 1828, when his two sons, Mikhail and Fyodor, were eight and seven respectively, he was promoted to collegiate assessor, a position which raised his legal status to that of the nobility and enabled him to acquire a small estate in Darovoye, a town about 150 km (100 miles) from Moscow, where the family usually spent the summers.

He moved clumsily and jerkily; his uniform hung awkwardly on him; and his knapsack, shako and rifle all looked like some sort of fetter he had been forced to wear for a time and which lay heavily on him.

"[27] Dostoevsky's character and interests made him an outsider among his 120 classmates: he showed bravery and a strong sense of justice, protected newcomers, aligned himself with teachers, criticised corruption among officers, and helped poor farmers.

[28][29] Signs of Dostoevsky's epilepsy may have first appeared on learning of the death of his father on 16 June 1839,[30] although the reports of a seizure originated from accounts written by his daughter (later expanded by Sigmund Freud[31]) which are now considered to be unreliable.

His friend Dmitry Grigorovich, with whom he was sharing an apartment at the time, took the manuscript to the poet Nikolay Nekrasov, who in turn showed it to the influential literary critic Vissarion Belinsky.

The negative reception of these stories, combined with his health problems and Belinsky's attacks, caused him distress and financial difficulty, but this was greatly alleviated when he joined the utopian socialist Beketov circle, a tightly knit community which helped him to survive.

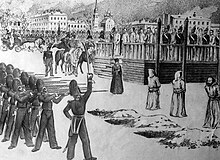

The story of a young man sentenced to death by firing squad but reprieved at the last moment is recounted by the main character, Prince Myshkin, who describes the experience from the point of view of the victim, and considers the philosophical and spiritual implications.

From dusk to dawn it was impossible not to behave like pigs ... Fleas, lice, and black beetles by the bushel ...[55][missing long citation]Classified as "one of the most dangerous convicts", Dostoevsky had his hands and feet shackled until his release.

[60] Before moving in mid-March to Semipalatinsk, where he was forced to serve in the Siberian Army Corps of the Seventh Line Battalion, Dostoevsky met geographer Pyotr Semyonov and ethnographer Shokan Walikhanuli.

[64] In 1859 he was released from military service because of deteriorating health and was granted permission to return to European Russia, first to Tver, where he met his brother for the first time in ten years, and then to St Petersburg.

[77] Dostoevsky returned to Saint Petersburg in mid-September and promised his editor, Fyodor Stellovsky, that he would complete The Gambler, a short novel focused on gambling addiction, by November, although he had not yet begun writing it.

[d] After hearing news that the socialist revolutionary group "People's Vengeance" had murdered one of its own members, Ivan Ivanov, on 21 November 1869, Dostoevsky began writing Demons.

[93][94] Dostoevsky revived his friendships with Maykov and Strakhov and made new acquaintances, including church politician Terty Filipov and the brothers Vsevolod and Vladimir Solovyov.

Nikolay Nekrasov suggested that he publish A Writer's Diary in Notes of the Fatherland; he would receive 250 rubles for each printer's sheet – 100 more than the text's publication in The Russian Messenger would have earned.

He was a frequent guest in several salons in Saint Petersburg and met many famous people, including Countess Sophia Tolstaya, Yakov Polonsky, Sergei Witte, Alexey Suvorin, Anton Rubinstein and Ilya Repin.

That summer, he was elected to the honorary committee of the Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale, whose members included Victor Hugo, Ivan Turgenev, Paul Heyse, Alfred Tennyson, Anthony Trollope, Henry Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Leo Tolstoy.

[123] According to Anna Dostoevskaya's memoirs, Dostoevsky once asked his sister's sister-in-law, Yelena Ivanova, whether she would marry him, hoping to replace her mortally ill husband after he died, but she rejected his proposal.

He claimed that Catholicism had continued the tradition of Imperial Rome and had thus become anti-Christian and proto-socialist,[132] inasmuch as the Church's interest in political and mundane affairs led it to abandon the idea of Christ.

[149] Through his visits to western Europe and discussions with Herzen, Grigoriev, and Strakhov, Dostoevsky discovered the Pochvennichestvo movement and the theory that the Catholic Church had adopted the principles of rationalism, legalism, materialism, and individualism from ancient Rome and had passed on its philosophy to Protestantism and consequently to atheistic socialism.

Numerous memorials were inaugurated in cities and regions such as Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Semipalatinsk, Kusnetsk, Darovoye, Staraya Russa, Lyublino, Tallinn, Dresden, Baden-Baden and Wiesbaden.

[190] Basing his estimation on stated criteria of enduring art and individual genius, Nabokov judges Dostoevsky "not a great writer, but rather a mediocre one—with flashes of excellent humour but, alas, with wastelands of literary platitudes in between."

Poor Folk is an epistolary novel that depicts the relationship between the small, elderly official Makar Devushkin and the young seamstress Varvara Dobroselova, remote relatives who write letters to each other.

He describes himself as vicious, squalid and ugly; the chief focuses of his polemic are the "modern human" and his vision of the world, which he attacks severely and cynically, and towards which he develops aggression and vengefulness.

[209] Crime and Punishment follows the mental anguish and moral dilemmas of Rodion Raskolnikov, an impoverished ex-student in Saint Petersburg who plans to kill an unscrupulous pawnbroker, an old woman who stores money and valuable objects in her flat.

He theorises that with the money he could liberate himself from poverty and go on to perform great deeds, and seeks to convince himself that certain crimes are justifiable if they are committed in order to remove obstacles to the higher goals of 'extraordinary' men.

[210] In contrast, Grigory Eliseev of the radical magazine The Contemporary called the novel a "fantasy according to which the entire student body is accused without exception of attempting murder and robbery".

[221][219][220] Sigmund Freud wrote an essay called "Dostoevsky and Parricide" (German: Dostojewski und die Vatertötung) as an introductory article to a scholarly collection on The Brothers Karamazov.