Richard Wright (author)

Much of his literature concerns racial themes, especially related to the plight of African Americans during the late 19th to mid 20th centuries suffering discrimination and violence.

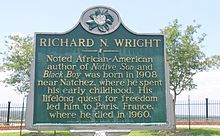

Richard Nathaniel Wright was born on September 4, 1908, at Rucker's Plantation, between the train town of Roxie and the larger river city of Natchez, Mississippi.

The Wrights were forced to flee after Silas Hoskins "disappeared", reportedly killed by a white man who coveted his successful saloon business.

[8] After his mother became incapacitated by a stroke, Richard was separated from his younger brother and lived briefly with his uncle Clark Wilson and aunt Jodie in Greenwood, Mississippi.

Soon Richard with his younger brother and mother returned to the home of his maternal grandmother, which was now in the state capital, Jackson, Mississippi, where he lived from early 1920 until late 1925.

[9] In his grandparents' Seventh-day Adventist home, Richard was miserable, largely because his controlling aunt and grandmother tried to force him to pray so he might build a relationship with God.

His aunt's and grandparents' overbearing attempts to control him caused him to carry over hostility towards Biblical and Christian teachings to solve life's problems.

[7] At the age of 15, while in eighth grade, Wright published his first story, "The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre", in the local Black newspaper Southern Register.

Determined not to be called an Uncle Tom, Richard refused to deliver the principal's address, written to avoid offending the white school district officials.

[13] His family joined the Great Migration, when tens of thousands of blacks left the South to seek opportunities in the more economically prosperous northern and mid-western industrial cities.

[25] His ultimate goal (looking at other labor unions as inspiration) was the development of NNC-sponsored publications, exhibits, and conferences alongside the Federal Writers' Project to get work for black artists.

This assignment compiled quotes from interviews preceded by an introductory paragraph, thus allowing him time for other pursuits like the publication of Uncle Tom's Children a year later.

[28] He would ultimately break from the Communist Party when they broke from a tradition against segregation and racism and joined Stalinists supporting the US entering World War II in 1941.

This text was an excerpt of his autobiography scheduled to be published as American Hunger but was removed from the actual publication of Black Boy upon request by the Book of the Month Club.

[29] Indeed, his relations with the party turned violent; Wright was threatened at knifepoint by fellow-traveler co-workers, denounced as a Trotskyite in the street by strikers, and physically assaulted by former comrades when he tried to join them during the 1936 Labour Day march.

The publication and favorable reception of Uncle Tom's Children improved Wright's status with the Communist party and enabled him to establish a reasonable degree of financial stability.

Based on his collected short stories, Wright applied for and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which gave him a stipend allowing him to complete Native Son.

Wright also wrote the text to accompany a volume of photographs chosen by Rosskam, which were almost completely drawn from the files of the Farm Security Administration.

Their collaboration, 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States, was published in October 1941 to wide critical acclaim.

His relationship with the latter ended in acrimony after Baldwin published his essay "Everybody's Protest Novel"[22] (collected in Notes of a Native Son), in which he criticized Wright's portrayal of Bigger Thomas as stereotypical.

In 1949, Wright contributed to the anti-communist anthology The God That Failed; his essay had been published in the Atlantic Monthly three years earlier and was derived from the unpublished portion of Black Boy.

Before Wright returned to Paris, he gave a confidential report to the United States consulate in Accra on what he had learned about Nkrumah and his political party.

By November 1959, his wife had found a London apartment, but Wright's illness and "four hassles in twelve days" with British immigration officials ended his desire to live in England.

Wright's last display of explosive energy occurred on November 8, 1960, in his polemical lecture "The Situation of the Black Artist and Intellectual in the United States", delivered to students and members of the American Church in Paris.

An omnibus edition containing Wright's political works was published under the title Three Books from Exile: Black Power; The Color Curtain; and White Man, Listen!

In August 1939, with Ralph Ellison as best man,[57] Wright married Dhimah Rose Meidman,[58] a modern dance teacher of Russian Jewish ancestry.

In this capacity, she unsuccessfully sued a biographer, the poet and writer Margaret Walker, in Wright v. Warner Books, Inc. She was a literary agent, and her clients included Simone de Beauvoir, Eldridge Cleaver, and Violette Leduc.

[68] Wright's stories published during the 1950s disappointed some critics who said that his move to Europe had alienated him from African Americans and separated him from his emotional and psychological roots.

[72] Rather, this book affected ideas and attitudes, and Native Son has been a force in the social and intellectual history of the United States in the last half of the 20th century.

Notably, Paul Gilroy has argued that "the depth of his philosophical interests has been either overlooked or misconceived by the almost exclusively literary inquiries that have dominated analysis of his writing".