Géza Gyóni

Born Géza Áchim to a "crusading Lutheran family" in the small village of Gyón, near Dabas, in Austria-Hungary,[1] Gyóni was one of the seven children of a pastor of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Hungary.

In November 1907, Gyóni was called up to the Austro-Hungarian Army, and spent eighteen months breaking rocks and building railway lines in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which he did not at all enjoy and which bred a very strong streak of pacifism in him.

In June 1914, police interrogation of the teenaged conspirators responsible for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, all of whom were members of the Unification or Death paramilitary organization, exposed that the pistols and bombs used, as well as cyanide capsules for use in the event of capture, had been covertly supplied by the Kingdom of Serbia's military intelligence chief Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević.

According to Peter Sherwood, "Gyóni's first, still elated, poems from the Polish Front recall the 16th-century Hungarian poet Bálint Balassi's soldiers' songs of the marches, written during the campaign against the Turks.

"[6] During the Siege of Przemyśl, which has since been dubbed, "The Stalingrad of World War I",[7][8][9] Gyóni wrote poems to encourage the city's defenders and these verses were published there, under the title, Lengyel mezőkön, tábortűz melett (By Campfire on the Fields of Poland).

[11][12] Regular outbreaks of anti-semitic violence, as well as the religious persecution of Rusins and Ukrainians who belonged to the Eastern Catholic Churches, were to continue until the Imperial Russian Army was humiliatingly driven out of the region by the Gorlice–Tarnów offensive and into the Great Retreat of 1915.

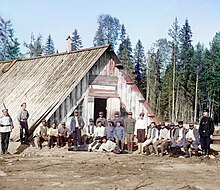

In the Krasnoyarsk camp, which was located upon a plateau 7 km outside of the city and held more than 13,000 Imperial German and Austro-Hungarian POWs,[14] Gyóni learnt of the full actions of Jenő Rákosi, the politician who had been weaponizing his verse for wartime propaganda.

Central Powers POWs who spoke Slavic languages were generally treated favorably by their Tsarist captors, due to both extreme Slavophilism and also in the hopes of recruiting them to switch sides and fight for the Allies.

German- and Hungarian-speaking prisoners, on the other hand, were treated so inhumanely and with such unnecessary brutality that,[15] according to historian Alfred Maurice de Zayas, the post-Armistice government of the Weimar Republic spent many years investigating and ultimately ruled that the treatment of POWs in Russian Imperial custody was a war crime according to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

[16] Even so, Gyóni went on to write perhaps his finest poetry as a POW in Krasnoyarsk and produced the collection Levelek a kálváriáról és más költemények (Letters from Golgotha and Other Poems) which was published in 1916, based on manuscripts sent through the lines.

[18] Géza Gyóni's last collection, Rabságban (In Captivity), consists of poems that were brought back to the truncated post-Treaty of Trianon Kingdom of Hungary by a fellow POW.