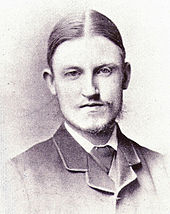

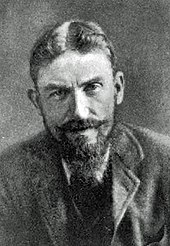

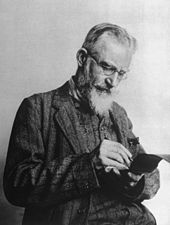

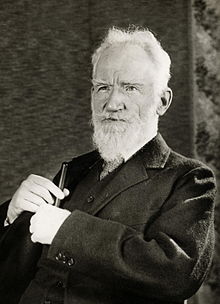

George Bernard Shaw

By the early twentieth century his reputation as a dramatist was secured with a series of critical and popular successes that included Major Barbara, The Doctor's Dilemma, and Caesar and Cleopatra.

His appetite for politics and controversy remained undiminished; by the late 1920s, he had largely renounced Fabian Society gradualism, and often wrote and spoke favourably of dictatorships of the right and left—he expressed admiration for both Mussolini and Stalin.

In the final decade of his life, he made fewer public statements but continued to write prolifically until shortly before his death, aged ninety-four, having refused all state honours, including the Order of Merit in 1946.

Since Shaw's death scholarly and critical opinion about his works has varied, but he has regularly been rated among British dramatists as second only to Shakespeare; analysts recognise his extensive influence on generations of English-language playwrights.

Lee's students often gave him books, which the young Shaw read avidly;[13] thus, as well as gaining a thorough musical knowledge of choral and operatic works, he became familiar with a wide spectrum of literature.

[48] After a rally in Trafalgar Square addressed by Besant was violently broken up by the authorities on 13 November 1887 ("Bloody Sunday"), Shaw became convinced of the folly of attempting to challenge police power.

[77] In the 1890s Shaw's plays were better known in print than on the West End stage; his biggest success of the decade was in New York in 1897, when Richard Mansfield's production of the historical melodrama The Devil's Disciple earned the author more than £2,000 in royalties.

[102] Shaw admired other figures in the Irish Literary Revival, including George Russell[103] and James Joyce,[104] and was a close friend of Seán O'Casey, who was inspired to become a playwright after reading John Bull's Other Island.

Shaw viewed this outcome with scepticism; he had a low opinion of the new prime minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, and saw the Labour members as inconsequential: "I apologise to the Universe for my connection with such a body".

"[134] Despite his errant reputation, Shaw's propagandist skills were recognised by the British authorities, and early in 1917 he was invited by Field Marshal Haig to visit the Western Front battlefields.

[148] After the London premiere in October 1921 The Times concurred with the American critics: "As usual with Mr Shaw, the play is about an hour too long", although containing "much entertainment and some profitable reflection".

[174] In March 1933, he was a co-signatory to a letter in The Manchester Guardian protesting at the continuing misrepresentation of Soviet achievements: "No lie is too fantastic, no slander is too stale ... for employment by the more reckless elements of the British press.

[186] Despite his contempt for Hollywood and its aesthetic values, Shaw was enthusiastic about cinema, and in the middle of the decade wrote screenplays for prospective film versions of Pygmalion and Saint Joan.

[197] Although Shaw's works since The Apple Cart had been received without great enthusiasm, his earlier plays were revived in the West End throughout the Second World War, starring such actors as Edith Evans, John Gielgud, Deborah Kerr and Robert Donat.

[229] Major Barbara (1905) presents ethical questions in an unconventional way, confounding expectations that in the depiction of an armaments manufacturer on the one hand and the Salvation Army on the other the moral high ground must invariably be held by the latter.

[241] Shaw named Shakespeare (King Lear) and Chekhov (The Cherry Orchard) as important influences on the piece, and critics have found elements drawing on Congreve (The Way of the World) and Ibsen (The Master Builder).

[241][242] The short plays range from genial historical drama in The Dark Lady of the Sonnets and Great Catherine (1910 and 1913) to a study of polygamy in Overruled; three satirical works about the war (The Inca of Perusalem, O'Flaherty V.C.

[258] Shaw had two regular targets for his more extreme comments about Shakespeare: undiscriminating "Bardolaters", and actors and directors who presented insensitively cut texts in over-elaborate productions.

A New York Times report dated 10 December 1933 quoted a recent Fabian Society lecture in which Shaw had praised Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin: "[T]hey are trying to get something done, [and] are adopting methods by which it is possible to get something done".

[271] As late as the Second World War, in Everybody's Political What's What, Shaw blamed the Allies' "abuse" of their 1918 victory for the rise of Hitler, and hoped that, after defeat, the Führer would escape retribution "to enjoy a comfortable retirement in Ireland or some other neutral country".

The eponymous girl, intelligent, inquisitive, and converted to Christianity by insubstantial missionary teaching, sets out to find God, on a journey that after many adventures and encounters, leads her to a secular conclusion.

[284] Among Shaw's many regular correspondents were his childhood friend Edward McNulty; his theatrical colleagues (and amitiés amoureuses) Mrs Patrick Campbell and Ellen Terry; writers including Lord Alfred Douglas, H. G. Wells and G. K. Chesterton; the boxer Gene Tunney; the nun Laurentia McLachlan; and the art expert Sydney Cockerell.

[292] Shaw was a poseur and a puritan; he was similarly a bourgeois and an antibourgeois writer, working for Hearst and posterity; his didacticism is entertaining and his pranks are purposeful; he supports socialism and is tempted by fascism.

A later out-of-court agreement provided a sum of £8,300 for spelling reform; the bulk of his fortune went to the residuary legatees—the British Museum, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and the National Gallery of Ireland.

[303] Despite his expressed wish to be fair to Hitler,[176] he called anti-Semitism "the hatred of the lazy, ignorant fat-headed Gentile for the pertinacious Jew who, schooled by adversity to use his brains to the utmost, outdoes him in business".

He called vaccination "a peculiarly filthy piece of witchcraft";[306] in his view immunisation campaigns were a cheap and inadequate substitute for a decent programme of housing for the poor, which would, he declared, be the means of eradicating smallpox and other infectious diseases.

Shaw did not found a school of dramatists as such, but Crawford asserts that today "we recognise [him] as second only to Shakespeare in the British theatrical tradition ... the proponent of the theater of ideas" who struck a death-blow to 19th-century melodrama.

[322] The following year, in a contrary assessment, the playwright John Osborne castigated The Guardian's theatre critic Michael Billington for referring to Shaw as "the greatest British dramatist since Shakespeare".

[324] Two further aspects of Shaw's theatrical legacy are noted by Crawford: his opposition to stage censorship, which was finally ended in 1968, and his efforts which extended over many years to establish a National Theatre.

[326] In the same year, Mark Lawson wrote in The Guardian that Shaw's moral concerns engaged present-day audiences, and made him—like his model, Ibsen—one of the most popular playwrights in contemporary British theatre.