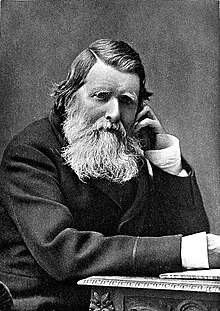

John Ruskin

[5] Margaret Ruskin, an evangelical Christian, more cautious and restrained than her husband, taught young John to read the Bible from beginning to end, and then to start all over again, committing large portions to memory.

[4] He was educated at home by his parents and private tutors, including Congregationalist preacher Edward Andrews,[8] whose daughters, Mrs Eliza Orme and Emily Augusta Patmore were later credited with introducing Ruskin to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

During a six-week break at Leamington Spa to undergo Dr Jephson's (1798–1878) celebrated salt-water cure, Ruskin wrote his only work of fiction, the fable The King of the Golden River (not published until December 1850 (but imprinted 1851), with illustrations by Richard Doyle).

In Lucca he saw the Tomb of Ilaria del Carretto by Jacopo della Quercia, which Ruskin considered the exemplar of Christian sculpture (he later associated it with the then object of his love, Rose La Touche).

A frequent visitor, letter-writer, and donor of pictures and geological specimens to the school, Ruskin approved of the mixture of sports, handicrafts, music and dancing encouraged by its principal, Miss Bell.

[90] He had, however, doubted his Evangelical Christian faith for some time, shaken by Biblical and geological scholarship that was claimed to have undermined the literal truth and absolute authority of the Bible:[91] "those dreadful hammers!"

[95] Following his crisis of faith, and urged to political and economic work by his professed "master" Thomas Carlyle, to whom he acknowledged that he "owed more than to any other living writer", Ruskin shifted his emphasis in the late 1850s from art towards social issues.

Just as he had questioned aesthetic orthodoxy in his earliest writings, he now dissected the orthodox political economy espoused by John Stuart Mill, based on theories of laissez-faire and competition drawn from the work of Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Thomas Malthus.

[105] Others were enthusiastic, including Carlyle, who wrote, "I have read your Paper with exhilaration… Such a thing flung suddenly into half a million dull British heads… will do a great deal of good", declaring that they were "henceforth in a minority of two",[106] a notion which Ruskin seconded.

The essays were praised and paraphrased in Gujarati by Mohandas Gandhi, a wide range of autodidacts cited their positive impact, the economist John A. Hobson and many of the founders of the British Labour party credited them as an influence.

'[118] Ruskin's widely admired lecture, Traffic, on the relation between taste and morality, was delivered in April 1864 at Bradford Town Hall, to which he had been invited because of a local debate about the style of a new Exchange building.

It was here that he said, "The art of any country is the exponent of its social and political virtues… she [England] must found colonies as fast and as far as she is able, formed of her most energetic and worthiest men;—seizing every piece of fruitful waste ground she can set her foot on…"[125] It has been claimed that Cecil Rhodes cherished a long-hand copy of the lecture, believing that it supported his own view of the British Empire.

Some of the diggers, who included Oscar Wilde, Alfred Milner and Ruskin's future secretary and biographer W. G. Collingwood, were profoundly influenced by the experience: notably Arnold Toynbee, Leonard Montefiore and Alexander Robertson MacEwen.

Ruskin's were paid by public subscription organised by the Fine Art Society, but Whistler was bankrupt within six months, and was forced to sell his house on Tite Street in London and move to Venice.

[149][150] In principle, Ruskin worked out a scheme for different grades of "Companion", wrote codes of practice, described styles of dress and even designed the Guild's own coins.

The Guild also encouraged independent but allied efforts in spinning and weaving at Langdale, in other parts of the Lake District and elsewhere, producing linen and other goods exhibited by the Home Arts and Industries Association and similar organisations.

Ruskin directed his readers, the would-be traveller, to look with his cultural gaze at the landscapes, buildings and art of France and Italy: Mornings in Florence (1875–1877), The Bible of Amiens (1880–1885) (a close study of its sculpture and a wider history), St Mark's Rest (1877–1884) and A Guide to the Principal Pictures in… Venice (1877).

His last great work was his autobiography, Praeterita (1885–1889)[166] (meaning, 'Of Past Things'), a highly personalised, selective, eloquent but incomplete account of aspects of his life, the preface of which was written in his childhood nursery at Herne Hill.

He oversaw the construction of a larger harbour (from where he rowed his boat, the Jumping Jenny), and he altered the house (adding a dining room, a turret to his bedroom to give him a panoramic view of the lake, and he later extended the property to accommodate his relatives).

He built a reservoir and redirected the waterfall down the hills, adding a slate seat that faced the tumbling stream and craggy rocks rather than the lake, so that he could closely observe the fauna and flora of the hillside.

[170] As he had grown weaker, suffering prolonged bouts of mental illness, he had been looked after by his second cousin, Joan(na) Severn (formerly "companion" to Ruskin's mother) and she and her family inherited his estate.

Presently there was a commotion in the doorway, and over the heads and shoulders of tightly packed young men, a loose bundle was handed in and down the steps, till on the floor a small figure was deposited, which stood up and shook itself out, amused and good humoured, climbed on to the dais, spread out papers and began to read in a pleasant though fluting voice.

Ruskin's ideas on the preservation of open spaces and the conservation of historic buildings and places inspired his friends Octavia Hill and Hardwicke Rawnsley to help found the National Trust.

[191] Pioneers of town planning such as Thomas Coglan Horsfall and Patrick Geddes called Ruskin an inspiration and invoked his ideas in justification of their own social interventions; likewise the founders of the garden city movement, Ebenezer Howard and Raymond Unwin.

[210] Similarly, architectural theorist Lars Spuybroek has argued that Ruskin's understanding of the Gothic as a combination of two types of variation, rough savageness and smooth changefulness, opens up a new way of thinking leading to digital and so-called parametric design.

For Ruskin, creating true Gothic architecture involved the whole community, and expressed the full range of human emotions, from the sublime effects of soaring spires to the comically ridiculous carved grotesques and gargoyles.

[227] Although Ruskin wrote about architecture in many works over the course of his career, his much-anthologised essay "The Nature of Gothic" from the second volume of The Stones of Venice (1853) is widely considered to be one of his most important and evocative discussions of his central argument.

Its glory is in its Age, and in that deep sense of voicefulness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy, nay, even of approval or condemnation, which we feel in walls that have long been washed by the passing waves of humanity.

Ruskin believed that the economic theories of Adam Smith, expressed in The Wealth of Nations had led, through the division of labour to the alienation of the worker not merely from the process of work itself, but from his fellow workmen and other classes, causing increasing resentment.

[272][273][274][275] For many years, various Baskin-Robbins ice cream parlours prominently displayed a section of the statement in framed signs: "There is hardly anything in the world that someone cannot make a little worse and sell a little cheaper, and the people who consider price alone are that man's lawful prey.

Middle: Ruskin in middle-age, as Slade Professor of Art at Oxford (1869–1879). From 1879 book.

Bottom: John Ruskin in old age by Frederick Hollyer . 1894 print.