G. K. Chesterton

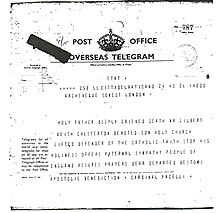

Gilbert Keith Chesterton KC*SG (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English author, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic.

Father Brown is perpetually correcting the incorrect vision of the bewildered folks at the scene of the crime and wandering off at the end with the criminal to exercise his priestly role of recognition, repentance and reconciliation.

For example, in the story "The Flying Stars", Father Brown entreats the character Flambeau to give up his life of crime: "There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don't fancy they will last in that trade.

"[19] Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as George Bernard Shaw,[20] H. G. Wells, Bertrand Russell and Clarence Darrow.

[35] Near the end of Chesterton's life, Pope Pius XI invested him as Knight Commander with Star of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great (KC*SG).

Behind the Johnsonian fancy dress, so reassuring to the British public, he concealed the most serious and revolutionary designs—concealing them by exposure ... Chesterton's social and economic ideas ... were fundamentally Christian and Catholic.

He reached a high imaginative level with The Napoleon of Notting Hill, and higher with The Man Who Was Thursday, romances in which he turned the Stevensonian fantasy to more serious purpose.

Gilbert Chesterton continued to understand the youngest and latest comers as he understood the forefathers in our great corpus of English verse and prose.

[60] Several lines of the hymn appear in the beginning of the song "Revelations" by the British heavy metal band Iron Maiden on their 1983 album Piece of Mind.

Chesterton "blames" England for historically building up Prussia against Austria, and for its pacifism, especially among wealthy British Quaker political donors, who prevented Britain from standing up to past Prussian aggression.

[81] According to historian Todd Endelman, who identified Chesterton as among the most vocal critics, "The Jew-baiting at the time of the Boer War and the Marconi scandal was linked to a broader protest, mounted in the main by the Radical wing of the Liberal Party, against the growing visibility of successful businessmen in national life and their challenge to what were seen as traditional English values.

Chesterton writes that popular perception of Jewish moneylenders could well have led Edward I's subjects to regard him as a "tender father of his people" for "breaking the rule by which the rulers had hitherto fostered their bankers' wealth".

[83][84] In The New Jerusalem, Chesterton dedicated a chapter to his views on the Jewish question: the sense that Jews were a distinct people without a homeland of their own, living as foreigners in countries where they were always a minority.

[86]In the same place he proposed the thought experiment (describing it as "a parable" and "a flippant fancy") that Jews should be admitted to any role in English public life on condition that they must wear distinctively Middle Eastern garb, explaining that "The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land.

[87] As Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise wrote in a posthumous tribute to Chesterton in 1937: When Hitlerism came, he was one of the first to speak out with all the directness and frankness of a great and unabashed spirit.

[79] Mayers records that despite "his hostility towards Nazi antisemitism … [it is unfortunate that he made] claims that 'Hitlerism' was a form of Judaism, and that the Jews were partly responsible for race theory".

[79] In The Judaism of Hitler, as well as in A Queer Choice and The Crank, Chesterton made much of the fact that the very notion of "a Chosen Race" was of Jewish origin, saying in The Crank: "If there is one outstanding quality in Hitlerism it is its Hebraism" and "the new Nordic Man has all the worst faults of the worst Jews: jealousy, greed, the mania of conspiracy, and above all, the belief in a Chosen Race".

[79] In The Everlasting Man, while writing about human sacrifice, Chesterton suggested that medieval stories about Jews killing children might have resulted from a distortion of genuine cases of devil worship.

[91] Likewise, Ann Farmer, author of Chesterton and the Jews: Friend, Critic, Defender,[92][93] writes, "Public figures from Winston Churchill to Wells proposed remedies for the 'Jewish problem' – the seemingly endless cycle of anti-Jewish persecution – all shaped by their worldviews.

"[95] He condemned the proposed wording for such measures as being so vague as to apply to anyone, including "Every tramp who is sulk, every labourer who is shy, every rustic who is eccentric, can quite easily be brought under such conditions as were designed for homicidal maniacs.

[95] Chesterton mocked the idea that poverty was a result of bad breeding: "[it is a] strange new disposition to regard the poor as a race; as if they were a colony of Japs or Chinese coolies ...

He endorsed Cunninghame Graham and Compton Mackenzie for the post of Lord Rector of Glasgow University in 1928 and 1931 respectively and praised Scottish Catholics as "patriots" in contrast to Anglophile Protestants such as John Knox.

[99] James Parker, in The Atlantic, gave a modern appraisal: In his vastness and mobility, Chesterton continues to elude definition: He was a Catholic convert and an oracular man of letters, a pneumatic cultural presence, an aphorist with the production rate of a pulp novelist.

He was a modernist, acutely alive to the rupture in consciousness that produced Eliot's "The Hollow Men"; he was an anti-modernist...a parochial Englishman and a post-Victorian gasbag; he was a mystic wedded to eternity.

Touched once by the live wire of his thought, you don't forget it ... His prose ... [is] supremely entertaining, the stately outlines of an older, heavier rhetoric punctually convulsed by what he once called (in reference to the Book of Job) "earthquake irony".

The current Bishop of Northampton, David Oakley, has agreed to preach at a Mass during a Chesterton pilgrimage in England (the route goes through London and Beaconsfield, which are both connected to his life), and some have speculated he may be more favourable to the idea.

[citation needed] His novel The Man Who Was Thursday inspired the Irish Republican leader Michael Collins with the idea that "If you didn't seem to be hiding nobody hunted you out.

[106] Another convert was Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan, who said that the book What's Wrong with the World (1910) changed his life in terms of ideas and religion.

[107] The author Neil Gaiman stated that he grew up reading Chesterton in his school's library, and that The Napoleon of Notting Hill influenced his own book Neverwhere.

[121] Another fictional character named Gil Chesterton is a food and wine critic who works for KACL, the Seattle radio station featured in the American television series Frasier.