Distributism

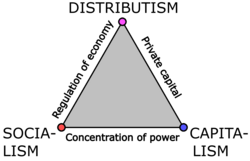

[7][8] Distributism views laissez-faire capitalism and state socialism as equally flawed and exploitative, due to their extreme concentration of ownership.

[5] According to distributists, the right to property is a fundamental right,[9] and the means of production should be spread as widely as possible rather than being centralised under the control of the state (statocracy), a few individuals (plutocracy), or corporations (corporatocracy).

[19] Some have seen it more as an aspiration, successfully realised in the short term by the commitment to the principles of subsidiarity and solidarity (built into financially independent local cooperatives and small family businesses).

[20] Particularly influential in the development of distributist theory were Catholic authors G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc,[13] two of distributism's earliest and strongest proponents.

[22] In 1891 Pope Leo XIII promulgated Rerum novarum, in which he addressed the "misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class" and spoke of how "a small number of very rich men" had been able to "lay upon the teeming masses of the laboring poor a yoke little better than that of slavery itself".

[25] Affirmed in the encyclical was the right of all men to own property,[26] the necessity of a system that allowed "as many as possible of the people to become owners",[27] the duty of employers to provide safe working conditions[28] and sufficient wages,[29] and the right of workers to unionise.

[31][32] Around the start of the 20th century, G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc drew together the disparate experiences of the various cooperatives and friendly societies in Northern England, Ireland, and Northern Europe into a coherent political theory which specifically advocated widespread private ownership of housing and control of industry through owner-operated small businesses and worker-controlled cooperatives.

In the United States in the 1930s, distributism was treated in numerous essays by Chesterton, Belloc and others in The American Review, published and edited by Seward Collins.

[34] In Rerum novarum, Leo XIII states that people are likely to work harder and with greater commitment if they possess the land on which they labour, which in turn will benefit them and their families as workers will be able to provide for themselves and their household.

He puts forward the idea that when men have the opportunity to possess property and work on it, they will "learn to love the very soil which yields in response to the labor of their hands, not only food to eat, but an abundance of the good things for themselves and those that are dear to them".

[35] He also states that owning property is beneficial for a person and his family and is, in fact, a right due to God having "given the earth for the use and enjoyment of the whole human race".

[39][40] Distributism requires either direct or indirect distribution of the means of production (productive assets)—in some ideological circles including the redistribution of wealth—to a wide portion of society instead of concentrating it in the hands of a minority of wealthy elites (as seen in its criticism of certain varieties of capitalism) or the hands of the state (as seen in its criticism of certain varieties of communism and socialism).

In Quadragesimo anno, Pope Pius XI provided the classical statement of the principle: "Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do".

[49] The Democratic Labour Party of Australia espouses distributism and does not hold the view of favouring the elimination of social security who, for instance, wish to "[r]aise the level of student income support payments to the Henderson poverty line".