Uncertainty principle

The energy–time relationship is widely used to relate quantum state lifetime to measured energy widths but its formal derivation is fraught with confusing issues about the nature of time.

It is vital to illustrate how the principle applies to relatively intelligible physical situations since it is indiscernible on the macroscopic[8] scales that humans experience.

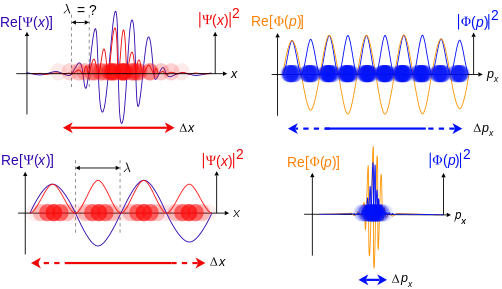

In quantum mechanics, the two key points are that the position of the particle takes the form of a matter wave, and momentum is its Fourier conjugate, assured by the de Broglie relation p = ħk, where k is the wavenumber.

In a quantum harmonic oscillator of characteristic angular frequency ω, place a state that is offset from the bottom of the potential by some displacement x0 as

Moreover, every squeezed coherent state also saturates the Kennard bound although the individual contributions of position and momentum need not be balanced in general.

The stronger uncertainty relations proved by Lorenzo Maccone and Arun K. Pati give non-trivial bounds on the sum of the variances for two incompatible observables.

[38] However, Yakir Aharonov and David Bohm[46][36] have shown that, in some quantum systems, energy can be measured accurately within an arbitrarily short time: external-time uncertainty principles are not universal.

[47][36] From Heisenberg mechanics, the generalized Ehrenfest theorem for an observable B without explicit time dependence, represented by a self-adjoint operator

Heisenberg's original version, however, was dealing with the systematic error, a disturbance of the quantum system produced by the measuring apparatus, i.e., an observer effect.

It is also possible to derive an uncertainty relation that, as the Ozawa's one, combines both the statistical and systematic error components, but keeps a form very close to the Heisenberg original inequality.

as the resulting fluctuation in the conjugate variable B, Kazuo Fujikawa[74] established an uncertainty relation similar to the Heisenberg original one, but valid both for systematic and statistical errors:

While formulating the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics in 1957, Hugh Everett III conjectured a stronger extension of the uncertainty principle based on entropic certainty.

[78] This conjecture, also studied by I. I. Hirschman[79] and proven in 1975 by W. Beckner[80] and by Iwo Bialynicki-Birula and Jerzy Mycielski[81] is that, for two normalized, dimensionless Fourier transform pairs f(a) and g(b) where the Shannon information entropies

Due to the Fourier transform relation between the position wave function ψ(x) and the momentum wavefunction φ(p), the above constraint can be written for the corresponding entropies as

(equivalently, from the fact that normal distributions maximize the entropy of all such with a given variance), it readily follows that this entropic uncertainty principle is stronger than the one based on standard deviations, because

We take the zeroth bin to be centered near the origin, with possibly some small constant offset c. The probability of lying within the jth interval of width δx is

[86] In his celebrated 1927 paper "Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik" ("On the Perceptual Content of Quantum Theoretical Kinematics and Mechanics"), Heisenberg established this expression as the minimum amount of unavoidable momentum disturbance caused by any position measurement,[2] but he did not give a precise definition for the uncertainties Δx and Δp.

Heisenberg wrote:It can be expressed in its simplest form as follows: One can never know with perfect accuracy both of those two important factors which determine the movement of one of the smallest particles—its position and its velocity.

[1]: 204 Throughout the main body of his original 1927 paper, written in German, Heisenberg used the word "Ungenauigkeit",[2] to describe the basic theoretical principle.

One way in which Heisenberg originally illustrated the intrinsic impossibility of violating the uncertainty principle is by using the observer effect of an imaginary microscope as a measuring device.

[91] Heisenberg did not care to formulate the uncertainty principle as an exact limit, and preferred to use it instead, as a heuristic quantitative statement, correct up to small numerical factors, which makes the radically new noncommutativity of quantum mechanics inevitable.

[96] Thus, the uncertainty principle actually states a fundamental property of quantum systems and is not a statement about the observational success of current technology.

[97] The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics and Heisenberg's uncertainty principle were, in fact, initially seen as twin targets by detractors.

The box could be weighed before a clockwork mechanism opened an ideal shutter at a chosen instant to allow one single photon to escape.

"Through this chain of uncertainties, Bohr showed that Einstein's light box experiment could not simultaneously measure exactly both the energy of the photon and the time of its escape.

"[103] In 1935, Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen published an analysis of spatially separated entangled particles (EPR paradox).

Experimental results confirm the predictions of quantum mechanics, ruling out EPR's basic assumption of local hidden variables.

[110]: 720 Some scientists, including Arthur Compton[111] and Martin Heisenberg,[112] have suggested that the uncertainty principle, or at least the general probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics, could be evidence for the two-stage model of free will.

All forms of spectroscopy, including particle physics use the relationship to relate measured energy line-width to the lifetime of quantum states.

Applications dependent on the uncertainty principle for their operation include extremely low-noise technology such as that required in gravitational wave interferometers.

Top: If wavelength λ is unknown, so are momentum p , wave-vector k and energy E (de Broglie relations). As the particle is more localized in position space, Δ x is smaller than for Δ p x .

Bottom: If λ is known, so are p , k , and E . As the particle is more localized in momentum space, Δ p is smaller than for Δ x .