Goidelic languages

[1] Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from Ireland through the Isle of Man to Scotland.

There are three modern Goidelic languages: Irish (Gaeilge), Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), and Manx (Gaelg).

[3][4] The medieval mythology of the Lebor Gabála Érenn places its origin in an eponymous ancestor of the Gaels and the inventor of the language, Goídel Glas.

Medieval Gaelic literature tells us that the kingdom of Dál Riata emerged in western Scotland during the 6th century.

Archaeologist Ewan Campbell says there is no archaeological evidence for a migration or invasion, and suggests strong sea links helped maintain a pre-existing Gaelic culture on both sides of the North Channel.

[8] Manx, the language of the Isle of Man, is closely akin to the Gaelic spoken in the Hebrides, the Irish spoken in northeast and eastern Ireland, and the now-extinct Galwegian Gaelic of Galloway (in southwest Scotland), with some influence from Old Norse through the Viking invasions and from the previous British inhabitants.

Classical Gaelic, otherwise known as Early Modern Irish,[9] covers the period from the 13th to the 18th century, during which time it was used as a literary standard[10] in Ireland and Scotland.

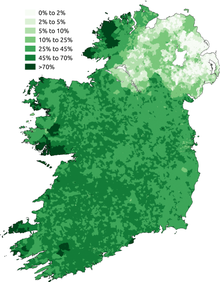

The legally defined Irish-speaking areas are called the Gaeltacht; all government institutions of the Republic, in particular the parliament (Oireachtas), its upper house (Seanad) and lower house (Dáil), and the prime minister (Taoiseach) have official names in this language, and some are only officially referred to by their Irish names even in English.

At present, the Gaeltachtaí are primarily found in Counties Cork, Donegal, Mayo, Galway, Kerry, and, to a lesser extent, in Waterford and Meath.

[16] Irish is also undergoing a revival in Northern Ireland and has been accorded some legal status there under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement but its official usage remains divisive to certain parts of the population.

[citation needed] Combined, this means that around one in three people (c. 1.85 million) on the island of Ireland can understand Irish at some level.

Despite the ascent in Ireland of the English and Anglicised ruling classes following the 1607 Flight of the Earls (and the disappearance of much of the Gaelic nobility), Irish was spoken by the majority of the population until the later 18th century, with a huge impact from the Great Famine of the 1840s.

Disproportionately affecting the classes among whom Irish was the primary spoken language, famine and emigration precipitated a steep decline in native speakers, which only recently has begun to reverse.

Some other parts of the Scottish Lowlands spoke Cumbric, and others Scots Inglis, the only exceptions being the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland where Norse was spoken.

Their numbers necessitated North American Gaelic publications and print media from Cape Breton Island to California.