Gaelic warfare

Irish warfare was for centuries centered on the Ceithearn, or Kern in English (and so pronounced in Gaelic), light skirmishing infantry who harried the enemy with missiles before charging.

John Dymmok, serving under Elizabeth I's lord-lieutenant of Ireland, described the kerns as: "... A kind of footman, slightly armed with a sword, a target (round shield) of wood, or a bow and sheaf of arrows with barbed heads, or else three darts, which they cast with a wonderful facility and nearness..."[1] For centuries the backbone of any Gaelic Irish army were these lightly armed foot soldiers.

Ceithearn were usually armed with a spear (gae) or sword (claideamh), long dagger (scian),[2] bow (bogha) and a set of javelins, or darts (gá-ín).

Indeed, from 1593 to 1601, the Gaelic Irish fought with the most up-to-date methods of warfare, including full reliance on firearms and modern military tactics.

Gallowglass mercenaries of the early 13th century have been depicted as having worn mail tunics and steel burgonet helmets but the overall majority of Gaelic warriors would have been protected only by a small shield.

In order to settle a dispute or merely to measure one's prowess, it was customary to challenge another individual warrior from the other army to ritual single combat to the death, while being cheered on by the opposing hosts.

[14] There were very few nucleated settlements, but after the 5th century some monasteries became the heart of small "monastic towns",[15][16] many of the Irish round towers were built after this period.

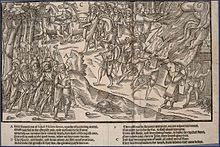

Gaelic Irish rebels, realizing that they could not expect or trust any quarter to be given upon surrender, began to improvise and set traps for armies besieging their towns.

[23] At Charlemont, a small force of less than 200 defenders and townsfolk was able to hold off the New Model Army for two months through heavy fighting after arming the entire town's populace including women.

In both instances, Irish defenders were able to compel the superior English forces into granting surrender agreements with generous terms through heavy fighting and attrition to the besieging armies.

In battle, the kern and lightly armed horsemen would charge the enemy line after intimidating them with shock tactics, war cries, horns and pipes.

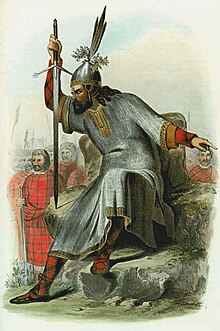

If the enemy formation did not break under the kern's charge, then heavily armed and armoured Irish soldiers were moved forward and would advance from the rear lines and attack, these units were replaced in the late 13th century by the Gallowglass or Gallóglaigh, who at first were Norse-Gaelic mercenaries but by the 15th century most large túatha in Ireland had fostered and developed their own hereditary forces of Gallowglass.

The primary function of Gaelic Heavy infantry was so lighter combatants such as Kern and Hobelars caught in thick fighting could strike, break free, re-group and tactically retreat behind the newly formed battle line if they needed to.

By the time of the Tudor reconquest of Ireland, the forces under Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone had adopted Continental pike-and-shot tactics.

Indeed, from the 16th century on, the Gaelic Irish fought with the most up-to-date methods of warfare, including full reliance on firearms and modern tactics.

Their formations consisted of a mix of Pikemen, musketeers and Gaelic swordsmen who began to be equipped and fight more like the continental units like the German Landsknecht or the Spanish Rodelero.

Muskets and other Firearms were widely used in combination with traditional Gaelic shock and hit and run tactics, often in ambushes against enemy columns on the march.

Later, when the Gaels came into contact with the Vikings, they realized the need for heavier weaponry, so as to make hacking through the much larger Norse shields and heavy mail-coats possible.

Irish and Scottish infantry troops fighting with the Claymore, axes and heavier armour, in addition to their own native darts and bows.

During the Scottish Wars of Independence, the Scots had to develop a means to counter the Anglo-Norman English and their devastating combined use of heavy cavalry and the Longbow.

[31][32] In early engagements, like when Schiltrons were used by William Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk, the immobile Phalanx-like formations proved vulnerable to the English Longbowmen without adequate cavalry support.

Wind instruments such as hollowed-out bull horns were often carried into battle by Chieftains or War leaders and used as a means to rally men into combat.

Bagpipes would eventually gain popularity among Gaelic clans and replaced other rallying instruments such as the blowing horn or carnyx, it can be attributed as being used from as early on as the 14th century.

[35] They fought and trained in a combination of Gaelic and Norse techniques, and were highly valued; they were hired throughout the British Isles at different times, though most famously in Ireland.

As Áed na nGall Ó Conchobair, the King of Connacht who defeated the Anglo-Normans, was known to travel with a retinue of 160 Gallowglass that he received as a dowry.

Despite the increased usage of firearms in Irish warfare following the 16th century, Gallowglass remained an integral part of Hugh Ó Neill's forces during the Nine Years' War.

[38] During his conflicts with the English crown, Robert the Bruce deployed the hobby for his campaign of guerilla warfare and mounted raids to great success, covering 60 to 70 miles (100 to 110 km) a day.

Hobelars were utilized as raiders across the border by both the English and Scots, they can be viewed as early predecessors to the reivers and moss-troopers of the Scottish borderlands.

Redshank was a nickname for Scottish or Ulster mercenaries from the Highlands and Western Isles contracted to fight in Ireland; they were a prominent feature of Irish armies throughout the 16th century.

[46] Later in the period, they may have adopted the targe and single-handed broadsword, a style of weaponry originally fashionable in early 16th-century Spain from where its use could have spread to Ireland.