Gaelic Ireland

The main kingdoms were Ulaid (Ulster), Mide (Meath), Laigin (Leinster), Muma (Munster, consisting of Iarmuman, Tuadmumain and Desmumain), Connacht, Bréifne (Breffny), In Tuaiscert (The North), and Airgíalla (Oriel).

[26] Acts of violence were generally settled by payment of compensation known as an éraic fine;[24] the Gaelic equivalent of the Welsh galanas and the Germanic weregild.

By the 8th century, the preferred form of marriage was one between social equals, under which a woman was technically legally dependent on her husband and had half his honor price, but could exercise considerable authority in regard to the transfer of property.

[31] Thus historian Patrick Weston Joyce could write that, relative to other European countries of the time, free women in Gaelic Ireland "held a good position" and their social and property rights were "in most respects, quite on a level with men".

[33] In Gaelic Ireland a kind of fosterage was common, whereby (for a certain length of time) children would be left in the care of others[35] to strengthen family ties or political bonds.

[13] They were a "highly mobile form of wealth and economic resource which could be quickly and easily moved to a safer locality in time of war or trouble".

[47] Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a brat (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a léine (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen).

[49][51][52] It is said that the Gaelic Irish took great pride in their long hair—for example, a person could be forced to pay the heavy fine of two cows for shaving a man's head against his will.

[52] Another style that was popular among some medieval Gaelic men was the glib (short all over except for a long, thick lock of hair towards the front of the head).

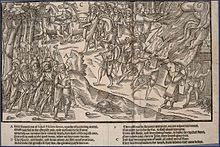

[55] Throughout the Middle Ages and for some time after, outsiders often wrote that the Irish style of warfare differed greatly from what they deemed to be the norm in Western Europe.

The ceithern wandered Ireland offering their services for hire and usually wielded swords, skenes (a kind of long knife), short spears, bows and shields.

[50] Artwork from Ireland's Gaelic period is found on pottery, jewellery, weapons, drinkware, tableware, stone carvings and illuminated manuscripts.

By about AD 600, after the Christianization of Ireland had begun, a style melding Irish, Mediterranean and Germanic Anglo-Saxon elements emerged, and was spread to Britain and mainland Europe by the Hiberno-Scottish mission.

These were the cruit (a small harp) and clairseach (a bigger harp with typically 30 strings), the timpan (a small string instrument played with a bow or plectrum), the feadan (a fife), the buinne (an oboe or flute), the guthbuinne (a bassoon-type horn), the bennbuabhal and corn (hornpipes), the cuislenna (bagpipes – see Great Irish Warpipes), the stoc and sturgan (clarions or trumpets), and the cnamha (castanets).

The main purpose of these gatherings was to promulgate and reaffirm the laws – they were read aloud in public that they might not be forgotten, and any changes in them carefully explained to those present.

With Palladius the eventual first Bishop of Ireland being sent during this period (mid-5th century) by Pope Celestine I to preach "ad Scotti in Christum"[8] or in other words to minister to the Scoti or Irish "believing in Christ".

[64] By the 8th century, the King of the Picts, Óengus mac Fergusso or Angus I expanded the influence of his kingdom using conquest, subjugation and diplomacy over the Gaels of Dal Riata, the Britons of Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons of Northumbria.

During this period there was regular warfare between the Vikings and the Irish, and between two separate groups of Norse from Lochlann: the Dubgaill and Finngaill (meaning dark and fair foreigners).

[65] In the mid-9th century, the crowns of both the Gaelic Dál Riata and the Celtic Pictish Kingdom were combined under the rule of one person, Cináid Mac Ailpin or Kenneth McAlpin.

Brian's descendants failed to maintain a unified throne, and regional squabbling over territory led indirectly to the invasion of the Normans under Richard de Clare (Strongbow) in 1169.

By the following year, he had obtained these services and in 1169 the main body of Norman, Welsh and Flemish forces landed in Ireland and quickly retook Leinster and the cities of Waterford and Dublin on behalf of Diarmait.

The leader of the Norman force, Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, more commonly known as Strongbow, married Diarmait's daughter, Aoife, and was named tánaiste to the Kingdom of Leinster.

However, with Diarmuid and Strongbow dead, Henry back in England, and Ruaidhrí unable to curb his vassals, the high kingship rapidly lost control of the country.

Whereas tributes like coyne and livery were exacted by chiefs within their own domains, "black rent" was protection payment in kind, typically as cattle, paid by those in neighbouring areas to avoid being raided.

[73] James started official policies of Anglicisation in order to convert the Gaelic nobility of Ireland to that of a Late Feudal model based upon English Law.

[citation needed] Hugh Red O'Donnell died in the archive castle of Simancas, Valladolid, in September 1602, when petitioning Philip III of Spain (1598–1621) for further assistance.

These Gaelic exiles brought with them invaluable knowledge of modern military tactics including push of pike warfare and Anti-Siege expertise.

The outright invasion and conquest by England's New Model Army under Oliver Cromwell and the "free-fire" zones and scorched earth tactics they used in the later stages of Wars of the Three Kingdoms marked a turning point.

The plague, famine, oppressive Cromwellian Settlements, plantation that followed and deliberate refugee crisis in the West of Ireland further suppressed the local Gaelic populace.

In the time leading up to the Great Famine of the 1840s, many priests believed that parishioner spirituality was paramount, resulting in a localized morphing of Gaelic and Catholic traditions.