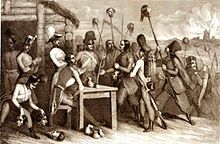

Galician Peasant Uprising of 1846

[4] In the autonomous Free City of Kraków, patriotic Polish intellectuals and nobles (szlachta) had made plans for a general uprising in partitioned Poland and intended to re-establish a unified and independent country.

The Austrian officials regarded it dismissively as "a barbaric place inhabited by strange people of questionable personal hygiene".

[5] The insurgent nobles made appeals to the peasants by reminding them of the popular Polish-Lithuanian hero Tadeusz Kościuszko and promising an end to serfdom.

[1][16] Hahn notes, "it is generally accepted as proven that the Austrian authorities deliberately exploited peasant dissatisfaction in order to suppress the noble (proto-national) uprising".

[17] The progressive ideals of the Polish insurgents in the Kraków uprising were praised, among others, by Karl Marx, who called it a "deeply democratic movement that aimed at land reform and other pressing social questions".

[18] As noted by several historians, the peasants were not so much acting out of loyalty to the Austrians as revolting against the oppressive feudal system (serfdom), of which the Polish nobles were the prime representatives and beneficiaries in the crownland of Galicia.

[21] Bideleux and Jeffries (2007) are among the dissenters to that view and cite Alan Sked's 1989 research that contends that "the Habsburg authorities – despite later charges of connivance – knew nothing about what was going on and were appalled at the results of the blood-lust".

[5] Hahn notes that during the events of 1846, "the Austrian bureaucracy played a dubious role that has not been completely explained, down to the present day".

[1] Magocsi et al. note that the peasants were punished by being forced to resume their feudal obligations while their leader, Szela, received a medal and a land grant.

[15][16] Serfdom, with corvée labor, existed in Galicia until 1848, and the 1846 massacre of the Polish szlachta is credited with helping to bring on its demise.

[1] In Vienna, the result of the Galician slaughter was a sense of complacency as what happened there was taken as evidence that the majority of the Austrian Empire's peoples were loyal to the House of Habsburg.

[20] A famous Ukrainian poet Ivan Franko, whose family were witnesses of the events, depicted the Galician slaughter in a number of works, particularly "Slayers" (1903), in which he describes the peasants as Masurians, as well as "Gryts and the nobleman's son" (1903), where Franko depicts a broader picture, showing both the aforementioned "Masurian slayers", and the Ruthenians, who opposed the Polish anti-Kaiser movement.