Kingdom of Galicia

Later, King Theodemar ordered an administrative and ecclesiastical division of his kingdom, with the creation of new bishoprics and the promotion of Lugo, which possessed a large Suebi community, to the level of Metropolitan Bishop along with Braga.

Theodemar's son and successor, King Miro, called for the Second Council of Braga, which was attended by all the bishops of the kingdom, from the Briton bishopric of Britonia in the Bay of Biscay, to Astorga in the east, and Coimbra and Idanha in the south.

The government of the Visigoths in Galicia did not totally disrupt the society, and the Suevi Catholic dioceses of Bracara, Dumio, Portus Cale or Magneto, Tude, Iria, Britonia, Lucus, Auria, Asturica, Conimbria, Lameco, Viseu, and Egitania continued to operate normally.

[30] This continuity led to the persistence of Galicia as a differentiated province within the realm, as indicated by the acts of several Councils of Toledo, chronicles such as that of John of Biclar, and in military laws such as the one extolled by Wamba[31] which was incorporated into the Liber Iudicum, the Visigothic legal code.

"Alfonso king of Galicia and of Asturias, after having ravaged Lisbon, the last city of Spain, sent during the winter the insignias of his victory, breastplates, mules, and Moor prisoners, through his legates Froia and Basiliscus."

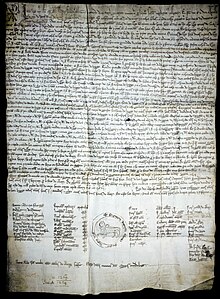

Each bishopric was divided into a number of territories or counties, named terras, condados, mandationes, commissos, or territorios in local charters,[49] which in the north were true continuations of the Suebic dioceses which frequently preserved old tribal divisions and denominations, such as Lemabos, Celticos, Postamarcos, Bregantinos, and Cavarcos.

The bishopric of Lugo was divided into counties, each one under the government of an infanzon (a lesser nobleman) as a concession of the bishop, while in the south, large and mighty territories such as the Portucalense became hereditary, passed down to the descendants of the 9th century's conquerors.

The elites were composed of counts, dukes, senatores, and other high noblemen, who were frequently related by marriage with the monarch,[52] and who usually claimed the most powerful positions in society, either as governors, bishops, or as palatine officials or companions of the king or queen.

In the country, most people were freemen, peasants, artisans, or infantrymen, who could freely choose a patron, or buy and sell properties, although they frequently fell prey to the greed of the big owners, leading many of them to a life of servitude.

Finally, servos, libertos, and pueros (servants, freedmen, and children), either obtained in war with the Moors or through trial, constituted a visible part of the society; they were employed as household workers (domésticos and scancianes), shepherds, and farmhands.

[78] However, by 1097 King Alfonso granted Henry the counties of Portugal and Coimbra, from the river Minho to the Tagus,[79] thus limiting the powers of Raymond, who by this time was securing an important nucleus of partisans in Galicia, including Count Pedro Fróilaz de Traba, whilst appointing his own notary, Diego Gelmírez, as bishop of Compostela.

[87] The coronation was intended to preserve the rights of the son of Raymond of Burgundy in Galicia, at a time when Urraca effectively delivered the kingdoms of Castile and León to her new husband, Alfonso the Battler of Aragon and Navarre.

[98] In his own realm, he continued his father's policies[99] by granting Cartas Póvoa or Foros (constitutional charters) to towns such as Padrón, Ribadavia, Noia, Pontevedra and Ribadeo,[100] most of them possessing important harbors or sited in rich valleys.

[104] Alfonso IX's long reign was characterized by his rivalry with Castile and Portugal,[105] and by the promotion of the royal power at the expense of the church and nobility, whilst maintaining his father's urban development policies.

[115] These new burgs also allowed a number of minor noble houses to consolidate power by occupying the new administrative and political offices, in open competition with the new classes: mayors, aldermen (regedores, alcaldes, justiças), agents and other officials (procuradores, notarios, avogados) and judges (juizes) of the town council; or mordomos and vigarios (leader and deputies) of the diverse guilds.

The Historia is an extensive chronicle of the deeds of the bishop of Compostela, Diego Gelmirez, and, though partisan, it is a source of great significance for the understanding of contemporary events and Galician society in the first half of the 12th century.

In 1231 Fernando established in his newly acquired kingdoms positions known in Galicia as meyrino maor,[134] a high official and personal representative of the king, in 1251 substituted by an adelantado mayor (Galician: endeantado maior), with even greater powers.

[144] This attempted secession lasted five years amid great political and military instability due to opposition from many sectors of society, including the party of Sancho's widow Maria de Molina, which was supported by the Castilian nobility, and the high Galician clergy.

After John's challenge, Ferdinand decided to send his brother Don Felipe to Galicia as Adelantado Mayor; he would later be granted the title of Pertigueiro Maior, or first minister and commander of the Terra de Santiago.

[148] In these conflicts, Don Felipe and the local nobility usually supported the councils' pretensions in opposition to the mighty and rich bishops,[149] although most of the time the military and economic influence of the archbishop of Santiago proved determinative in the maintenance of the status quo.

[176] With the capture of Ferrol, the Duke controlled the whole Kingdom of Galicia, as reported in the chronicles of Jean Froissart: «avoient mis en leur obeissance tout le roiaulme de Gallice».

After the defeat of the loyalist party, with their leaders consequently exiled in Portugal or dead abroad, Henry II and John I introduced a series of foreign noble houses in Galicia as tenants of important fiefs.

But during the 15th century, in the absence of solid leadership, such as exercised in the past by the archbishop of Santiago or by the Counts of Trastámara, the Kingdom of Galicia was reduced to a set of semi-independent and rival fiefdoms,[182] militarily important, but with little political influence abroad.

After an angry debate it was decided that noblemen should deliver all of their strongholds and castles to the officials of the Irmandade, resulting in the flight of many lesser nobles, while others resisted the armies of the Irmandiños ('little brothers'), only to be slowly beaten back into Castile and Portugal;[196] as described by a contemporary, 'the sparrows pursued the falcons'.

But in autumn of 1469 the exiled noblemen, joining forces, marched into Galicia: Pedro Alvares de Soutomaior entered from Portugal with gunmen and mercenaries; the archbishop Fonseca of Compostela from Zamora; and the Count of Lemos from Ponferrada.

[205] In 1479, the armies of Fonseca moved south again against Pedro Madruga, and, after a series of battles, forced the Count of Caminha into Portugal, although Tui, Salvaterra de Miño and other towns and strongholds were still held by his people and their Portuguese allies.

Ferdinand was declared Holy Roman Emperor and king of Hungary and Bohemia, while Philip inherited the Netherlands, Naples and Sicily, the Crown of Aragon and Castile, including the Kingdom of Galicia.

For example, in Alpujarra in the Kingdom of Granada in 1568, led by self-proclaimed king Muhammad ibn Umayya, Philip ordered the forced dispersal of 80,000 Granadian Muslims throughout the realm, and the introduction of Christians in their place.

This was due to both the disruption of trade relations with northern Europe, which since the Middle Ages had provided enormous wealth to the kingdom, and to England's constant operations in the region, staged in order to end Phillip's maritime expeditions, such as the Spanish Armada in 1588.

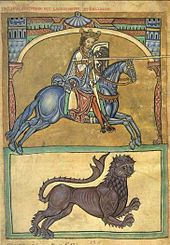

One was the need to differentiate between allies and adversaries on the battlefield, as facial protection in medieval helmets tended to obscure the combatants' faces, but also due to the high ornamental value of decorated shields with bright, crisp, and alternate shapes in the context of chivalrous society.