Galileo's Leaning Tower of Pisa experiment

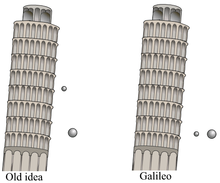

Between 1589 and 1592,[1] the Italian scientist Galileo Galilei (then professor of mathematics at the University of Pisa) is said to have dropped "unequal weights of the same material" from the Leaning Tower of Pisa to demonstrate that their time of descent was independent of their mass, according to a biography by Galileo's pupil Vincenzo Viviani, composed in 1654 and published in 1717.

[8] Two years later, mathematician Giambattista Benedetti questioned why two balls, one made of iron and one of wood, would fall at the same speed.

The experiment is described in Stevin's 1586 book De Beghinselen der Weeghconst (The Principles of Statics), a landmark book on statics: Let us take (as the highly educated Jan Cornets de Groot, the diligent researcher of the mysteries of Nature, and I have done) two balls of lead, the one ten times bigger and heavier than the other, and let them drop together from 30 feet high, and it will show, that the lightest ball is not ten times longer under way than the heaviest, but they fall together at the same time on the ground.

[9][10][11]At the time when Viviani asserts that the experiment took place, Galileo had not yet formulated the final version of his law of falling bodies.

[3]: 20 This was contrary to what Aristotle had taught: that heavy objects fall faster than the lighter ones, and in direct proportion to their weight.

Astronaut David Scott performed a version of the experiment on the Moon during the Apollo 15 mission in 1971, dropping a feather and a hammer from his hands.

Galileo's hypothesis that inertial mass (resistance to acceleration) equals gravitational mass (weight) was extended by Albert Einstein to include special relativity and that combination became a key concept leading to the development of the modern theory of gravity, general relativity.