Gallaeci

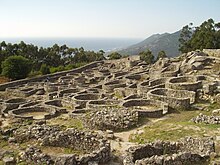

The Gallaecian way of life was based in land occupation especially by fortified settlements that are known in Latin language as "castra" (hillforts) or "oppida" (citadels); they varied in size from small villages of less than one hectare (more common in the northern territory) to great walled citadels with more than 10 hectares sometimes denominated oppida, being these latter more common in the Southern half of their traditional settlement and around the Ave river.

Many Galician modern day toponyms derive from these old settlements' names: Canzobre < Caranzovre < *Carantiobrixs, Trove < Talobre < *Talobrixs, Ombre < Anobre < *Anobrixs, Biobra < *Vidobriga, Bendollo < *Vindocelo, Andamollo < *Andamocelo, Osmo < Osamo < *Uxsamo, Sésamo < *Segisamo, Ledesma < *φletisama...[5]

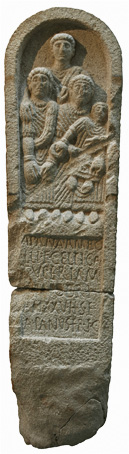

Associated archaeologically with the hill forts are the famous Gallaecian warrior statues - slightly larger than life size statues of warriors, assumed to be deified local heroes.The Gallaecian political organization is not known with certainty but it is very probable that they were divided into small independent chiefdoms who the Romans called populus or civitas, each one ruled by a local petty king or chief (princeps), as in other parts of Europe.

[citation needed] However, early allusions to the Gallaeci are present in ancient Greek and Latin authors prior to the conquest, which allows the reconstruction of a few historical events of this people since the second century BC.

[10] On his epic poem Punica, Silius Italicus gives a short description of these mercenaries and their military tactics:[11] […] Fibrarum et pennae divinarumque sagacem flammarum misit dives Gallaecia pubem, barbara nunc patriis ululantem carmina linguis, nunc pedis alterno percussa verbere terra ad numerum resonas gaudentem plauder caetras […] Rich Gallaecia sent its youths, wise in the knowledge of divination by the entrails of beasts, by feathers and flames, now howling barbarian songs in the tongues of their homelands, now alternately stamping the ground in their rhythmic dances until the ground rang, and accompanying the playing with sonorous shields.The Gallaeci came into direct contact with Rome relatively late, in the wake of the Roman punitive campaigns against their southern neighbours, the Lusitani and the Turduli Veteres.

After seizing the town of Talabriga (Marnel, Lamas do Vouga – Águeda) from the Turduli Veteres, he crushed an allegedly 60,000-strong Gallaeci relief army sent to support the Lusitani at a desperate and difficult battle near the Durius river, in which 50,000 Gallaicans were slain, 6,000 were taken prisoner and only a few managed to escape, before withdrawing south.

Again, the involvement of the Gallaeci in the latter conflict remains obscure, with Paulus Orosius[20] briefly mentioning that the Augustan legates Gaius Antistius Vetus and Gaius Firmius fought a difficult campaign to subdue the Gallaeci tribes of the more remote forested and mountainous parts of Gallaecia bordering the Atlantic Ocean, defeating them only after a series of severe battles, though no exact details are given.

After conquering Gallaecia, Augustus promptly used its territory – now part of his envisaged Transduriana Province, whose organization was entrusted to suffect consul Lucius Sestius Albanianus Quirinalis[21] – as a springboard to his rear offensive against the Astures.

The region remained one of the last redoubts of Celtic culture and language in the Iberian Peninsula well into the Roman imperial period, at least until the spread of Christianity and the Germanic invasions of the late 4th/early 5th centuries AD, when it was conquered by the Suevi and their Hasdingi Vandals' allies.