Gallaecian language

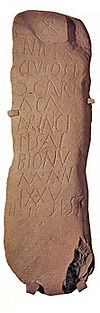

[2][3][4] As with the Illyrian, Ligurian and Thracian languages, the surviving corpus of Gallaecian is composed of isolated words and short sentences contained in local Latin inscriptions or glossed by classical authors, together with a number of names – anthroponyms, ethnonyms, theonyms, toponyms – contained in inscriptions, or surviving as the names of places, rivers or mountains.

In addition, some isolated words of Celtic origin preserved in the present-day Romance languages of north-west Iberia, including Galician, Portuguese, Asturian and Leonese are likely to have been inherited from ancient Gallaecian.

[7] Others point to major unresolved problems for this hypothesis, such as the mutually incompatible phonetic features, most notably the proposed preservation of Indo-European *p and the loss of *d in Lusitanian and the inconsistent outcome of the vocalic liquid consonants, which has led them to the conclusion that Lusitanian is a non-Celtic language and is not closely related to Gallaecian.

[12] Under the P/Q Celtic hypothesis, Gallaecian appears to be a Q-Celtic language, as evidenced by the following occurrences in local inscriptions: ARQVI, ARCVIVS, ARQVIENOBO, ARQVIENI[S], ARQVIVS, all probably from IE Paleo-Hispanic *arkʷios 'archer, bowman', retaining proto-Celtic *kʷ.

Nevertheless, some old toponyms and ethnonyms, and some modern toponyms, have been interpreted as showing kw / kʷ > p: Pantiñobre (Arzúa, composite of *kʷantin-yo- '(of the) valley' and *brix-s 'hill(fort)') and Pezobre (Santiso, from *kweityo-bris),[68] ethnonym COPORI "the Bakers" from *pokwero- 'to cook',[69] old place names Pintia, in Galicia and among the Vaccei, from PIE *penkwtó- > Celtic *kwenχto- 'fifth'.