Gallo-Roman enclosure of Le Mans

[J 3] This crisis encompassed political, military, and economic dimensions, as well as a period of heightened insecurity due to mounting pressures on the Empire's borders and the eruption of peasant revolts.

[A 2] The late enclosures were associated with a "new military, political, and administrative context", with a notable reduction in the area protected compared to the previous extent of cities.

"[J 3] The Rhine and Danube borders underwent significant reorganization, and the chief towns of cities were equipped with enclosures, which symbolized the "restored order and renewed power of Rome.

[BA 1] These constructions, which were likely undertaken with the Emperor's authorization, incorporated elements from High Empire structures and served as a symbol of prestige, even though the enclosed areas were smaller than the territories encompassed by the towns.

However, the presence of an oppidum on the site remains uncertain,[H 1] despite the discovery in 2010 of a mid-1st century BC occupation interpreted as a water sanctuary, a "small isolated complex.

[H 1] The city acquired institutions based on the Roman system, and a monumental temple dedicated to Mars Mullo, which was already present in Allonnes [fr], was constructed at the end of the 1st century.

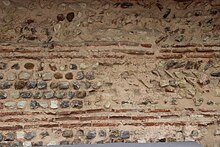

[A 11] The archaeological data suggest that the enclosure was built to a high standard and that the planning and execution of the work were carried out methodically and thoroughly, without undue haste.

[AI 4] Archaeological evidence suggests that private spaces were established within former buildings, with new constructions comprising earth, wood, and other organic materials.

"[G 3] Some scholars posit that the population in the 4th and early 5th centuries comprised civilians and military personnel tasked with maintaining security and ensuring the collection of taxes.

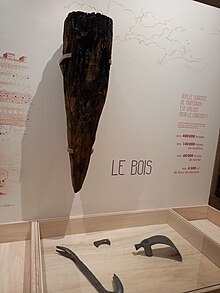

[A 34] Recent research has facilitated the study of mortars and bricks, the location of quarries, and the examination of wood usage in construction, such as stakes or scaffolding elements.

The use of these stakes may have been employed to secure the construction due to the challenging terrain,[AF 2][G 10] which consisted of sandy or clayey soil with numerous springs in some areas.

[A 45] In History of the Franks (III, 19), he also describes the significant role of Dijon as a fortress city with four gates, 33 towers, and enclosures over four meters thick.

[A 58] The uppermost rooms, accessible via a movable ladder,[A 58] are in a state of significant deterioration or lack thereof,[AH 6] and the covering is yet to be definitively identified.

[A 59] Excavations conducted in 1860 in this area indicate that the gates were equipped with a porch, one or two passages, and semicircular towers outside the enclosure,[A 60] in accordance with a "classical pattern.

"[A 61] The Saint-Martin Gate is situated at the end of a recess in the enclosure,[A 60] in alignment with Vitruvius' principle of roads approaching from the left and exposing the attackers' right flank.

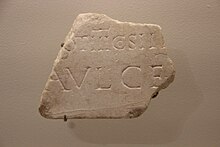

[AH 9] The decoration is linked to a local construction tradition identified on the remains of a cultic structure discovered on the site of the Jacobins in Le Mans and dated to 15–20.

[L 4] The maintenance of the enclosure was probably assumed by the bishop,[E 1] who served as "the principal relay of royal authority"[L 4] from the early Middle Ages onwards.

[L 3] The will of Bishop Bertrand of Le Mans, dated March 616, mentions an oratory dedicated to Saint Michael in a tower, which was likely constructed at this time.

"[G 1] Charles the Bald, the Duke of Maine who became King of the Franks in 856, temporarily transferred the ducal command to his son Louis the Stammerer and restored the enclosures in 869 to reinforce the city's defenses against incursions by the Bretons and Normans.

[N 2] The enclosures underwent modifications during the Hundred Years' War due to the prevailing sense of insecurity that followed the capture of King John the Good at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356.

[W 1] From the late 15th century, municipal charters granted the aldermen control over the enclosures, confirmed by a royal decree in 1687: the towers were then used for city council meetings, one of which is attested in 1489, or for other public uses, while others were rented out to residents.

[O 5] In 1683, the backfilling of the northwest corner by the canons resulted in the collapse of the enclosure over a length of approximately 50 meters, leading to the destruction of the buildings situated below, including the Church of Gourdaine.

[5] The period between 1680 and 1690 represents a significant shift in municipal policy,[O 5] marked by the filling in of ditches and the destruction of fortified structures dating back to the 15th and 16th centuries.

[P 1] Louis Maulny (circa 1681–1765), a counselor at the Presidial of his state, was the first true historian to study the building, describing it and dating it to the Roman Empire.

[S 1] Louis Moullin [fr] created approximately one hundred drawings in 1854, some of which serve as valuable testimonies due to the significant alterations that occurred in their surrounding areas in the subsequent decades.

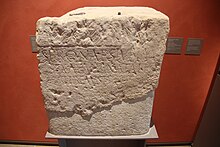

[C 2] Subsequently, Blanchet conducted a comparative analysis of the enclosures, concurrently examining numismatics and epigraphy, and concluded that they were constructed during the latter decades of the 3rd century.

[W 2] The edifice was found to be in a state of structural weakness during the 1970s,[F 2] with a collapse occurring in 1972 in the Saint-Benoît district[T 9] and another in 1976[A 118] on Rue des fossés Saint-Pierre,[C 3] close to the Saint-Pierre-la-Cour collegiate church [fr].

[F 2] A road project along the Sarthe was initiated in the late 1970s but was ultimately terminated due to objections from experts, including Joseph Guilleux,[V 1] who highlighted the potential damage to the structure[F 2] and criticized the "negligence of politicians.

[S 1] At a conference held in 1980, an evaluation was conducted,[C 4] and a cautionary statement was published[F 3] in the August issue of Archéologia [fr],[V 1] wherein the enclosure was designated a "national heritage treasure in danger.

"[F 4] Subsequently, a memorandum of understanding was concluded in 1980[T 9] or 1981 between the municipal authority and the state government to facilitate expanded research on the edifice,[A 116] its restoration,[C 3] and its enhancement.

|

Gallo-Roman enclosure

|

15th century

|

14th century

|

|

Ditches 14th century

|

13th century

|

|

|

11th century

|

16th century

|