Gallo-Roman enclosure of Tours

[3] This modification of the urban envelope seems to be accompanied by a profound change in construction methods: In the elevation of the walls, masonry is replaced by wood and earth, which does not contribute to the preservation of remains and may partly explain the lack of archaeological information from this period.

After formulating numerous hypotheses regarding the dating of the castrum, archaeologists and historians have reached a consensus that the structure was constructed for several years, or even two or three decades, in the first half of the 4th century.

[3] In 1979, Henri Galinié [fr] and Bernard Randoin proposed that the construction of the castrum may have been the cause or consequence of Tours' accession to the rank of provincial capital of the Roman province.

[HT 1] The small stones and terracotta (tubuli,[Note 3] brick, or tile fragments) are believed to have originated from private houses situated close to the rampart.

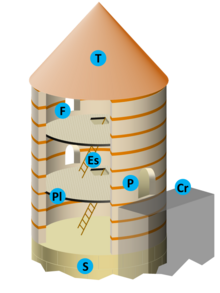

Above the base, the elevation (E) is composed of two small walls constructed of rubble masonry with pink mortar (2) interspersed at variable intervals with courses of bricks across their entire width (3).

These two small walls, with a width of 0.40 to 0.60 meters, form two formwork panels whose gap is filled with rubble composed of irregularly shaped stones, assembled with white mortar (4).

[18] This discovery, in conjunction with the interpretation of geophysical survey results by apparent resistivity [fr][Note 8] in the same area, suggests the potential existence of a gate at this point in the wall.

[19] It appears that this gate was already depicted around 1780 by the actor and illustrator Pierre Beaumesnil [fr], who was commissioned by the Academy of Inscriptions and Letters to reproduce ancient monuments in France, including those in Tours.

[Gal 6] The entire structure, comprising the bridge, the gate providing access to the Cité, and the fortified castrum setup, appears to function as a lock, allowing complete control over the river crossing.

Until the 1980s, it was assumed that the gates were relocated to the north from the median of the lateral walls (Hypothesis A in Figure III), thus continuing the decumanus of the High Empire city that would have crossed the castrum.

[Gal 5] The second hypothesis proposes that the road linking the towers, which passes further south in the castrum, would divide the enclosed space into two roughly equal northern and southern parts.

[Gal 3] Following the construction of the Arcis enclosure, likely in the 12th century,[21] it is plausible that the castrum no longer exists as an independent architectural entity but rather as a component of a larger complex.

[22] In response to this threat to his kingdom, Charles the Bald, as recorded in the annals of Saint-Bertin, requested in 869 that the walls of several cities in northern France, including Tours, be repaired.

[S3 3] It serves as the base for the governor's residence along its entire length and the Tours castle (north gable wall of the Mars Pavilion) for modern buildings.

[17] A proposed reconstruction of the castrum (3D animation), posted on the website of the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research [fr] (INRAP), depicts the general architectural layout of the enclosure and its structural integration with the amphitheater.

As of 2014, the available knowledge in this area remains fragmentary, based mainly on a few rare written sources (historical texts, charters, deeds of donation, or land exchanges), the results of excavations on site 3, and an archaeological survey at Paul-Louis-Courier High School.

Additionally, the area northeast of the cathedral apse (under the responsibility of Anne-Marie Jouquand, INRAP, as part of a high school expansion project)[Lef 4] and Bastien Lefebvre's work on the evolution of buildings within the old amphitheater's footprint were investigated.

[25] The disparate and fragmentary nature of the available evidence precludes the possibility of constructing a comprehensive picture of life in the Cité at any given moment in Late Antiquity or the Early Middle Ages.

[Aud 7] A diploma dated 919 attests to the existence, near the northeast corner of the castrum, in the second half of the 9th century, of a church (potentially located at the site of the current Saint-Libert Chapel) and a postern in the wall.

[S3 8] In the center of the Cité, preliminary excavations conducted before the construction activities at Paul-Louis Courier High School revealed evidence of domestic habitation, including a silo and a cesspit, which date back to the 9th century.

Site 3 appears to have been reserved throughout Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages for inhabitants belonging to some form of social or political elite, whose precise nature is yet to be defined.

[29] Despite the need for further advances to better understand this black earth, it is now accepted, even by those who envisioned a return to nature in ancient cities, that it reflects a persistent human presence but with totally renewed lifestyles.

Some rare civil buildings are attested in the Late Empire between these basilicas and the Cité, such as the site of Saint-Pierre-le-Puellier,[Aud 8] and a dwelling closer to the current city center, equipped with a bathhouse in the 3rd century.

[Aud 9] The lack of knowledge of the history of Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages in Tours can be largely attributed to two factors directly related to the constraints of urban archaeology.

[Gal 17] In 1784, actor and draughtsman Pierre Beaumesnil [fr] published, at the behest of the Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, the collection Antiquités et Monuments de la Touraine (1784).

This document reproduces several drawings of the 4th-century wall, including the north face, where a gate, subsequently lost but rediscovered in the early 2000s through geophysical prospecting methods, is visible.

The Late Empire enclosure was the subject of considerable attention, with Auvray collating previous discoveries associated with it and supplementing them with his observations in the form of a "promenade" along the rampart.

[S3 9] In 1978, a project to expand the Departmental Archives building presented the opportunity to conduct excavations at the foot of the castrum wall, in the southeast curvilinear part of the amphitheater.

In 1983, Luce Pietri published a doctoral thesis entitled La ville de Tours du IVe au VIe siècle.

[3] In 2008, in his doctoral thesis in archaeology, Bastien Lefebvre examined the evolution of the canonical district [fr] of Tours, which encompasses a portion of the city built on the ruins of the amphitheater.