Galvanic cell

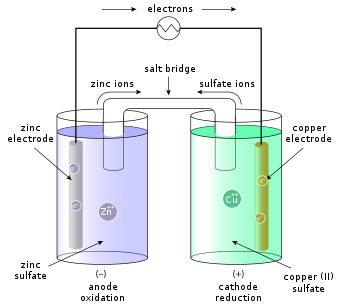

An example of a galvanic cell consists of two different metals, each immersed in separate beakers containing their respective metal ions in solution that are connected by a salt bridge or separated by a porous membrane.

[2] In 1780, Luigi Galvani discovered that when two different metals (e.g., copper and zinc) are in contact and then both are touched at the same time to two different parts of a muscle of a frog leg, to close the circuit, the frog's leg contracts.

The frog's leg, as well as being a detector of electrical current, was also the electrolyte (to use the language of modern chemistry).

A year after Galvani published his work (1790), Alessandro Volta showed that the frog was not necessary, using instead a force-based detector and brine-soaked paper (as electrolyte).

[4] Carlo Matteucci in his turn constructed a battery entirely out of biological material in answer to Volta.

This view ignored the chemical reactions at the electrode-electrolyte interfaces, which include H2 formation on the more noble metal in Volta's pile.

Faraday introduced new terminology to the language of chemistry: electrode (cathode and anode), electrolyte, and ion (cation and anion).

Thus Galvani incorrectly thought the source of electricity (or source of electromotive force (emf), or seat of emf) was in the animal, Volta incorrectly thought it was in the physical properties of the isolated electrodes, but Faraday correctly identified the source of emf as the chemical reactions at the two electrode-electrolyte interfaces.

The authoritative work on the intellectual history of the voltaic cell remains that by Ostwald.

[7] It was suggested by Wilhelm König in 1940 that the object known as the Baghdad battery might represent galvanic cell technology from ancient Parthia.

Replicas filled with citric acid or grape juice have been shown to produce a voltage.

[1] For example, when one immerses a strip of zinc metal (Zn) in an aqueous solution of copper sulfate (CuSO4), dark-colored solid deposits will collect on the surface of the zinc metal and the blue color characteristic of the Cu++ ion disappears from the solution.

When electrons are transferred directly from Zn to Cu++, the enthalpy of reaction is lost to the surroundings as heat.

In its simplest form, a half-cell consists of a solid metal (called an electrode) that is submerged in a solution; the solution contains cations (+) of the electrode metal and anions (−) to balance the charge of the cations.

[9] The full cell consists of two half-cells, usually connected by a semi-permeable membrane or by a salt bridge that prevents the ions of the more noble metal from plating out at the other electrode.

[9] A specific example is the Daniell cell (see figure), with a zinc (Zn) half-cell containing a solution of ZnSO4 (zinc sulfate) and a copper (Cu) half-cell containing a solution of CuSO4 (copper sulfate).

In addition, electrons flow through the external conductor, which is the primary application of the galvanic cell.

By separating the metals in two half-cells, their reaction can be controlled in a way that forces transfer of electrons through the external circuit where they can do useful work.

As this reaction continues, the half-cell with the metal A electrode develops a positively charged solution (because the metal A cations dissolve into it), while the other half-cell develops a negatively charged solution (because the metal B cations precipitate out of it, leaving behind the anions); unabated, this imbalance in charge would stop the reaction.

For instance, a typical 12 V lead–acid battery has six galvanic cells connected in series, with the anodes composed of lead and cathodes composed of lead dioxide, both immersed in sulfuric acid.

Large central office battery rooms – in a telephone exchange to provide power for subscribers' land-line telephones, for instance – may have many cells, connected both in series and parallel: Individual cells are connected in series as a battery of cells with some standard voltage (c. 40 V), and banks of such serial batteries, themselves connected in parallel, to provide adequate amperage to supply a typical peak demand for telephone connections.

The voltage (electromotive force Eo) produced by a galvanic cell can be estimated from the standard Gibbs free energy change in the electrochemical reaction according to:

where νe is the number of electrons transferred in the balanced half reactions, and F is Faraday's constant.

However, it can be determined more conveniently by the use of a standard potential table for the two half cells involved.

Thus, zinc metal will lose electrons to copper ions and develop a positive electrical charge.

7, "Equilibrium electrochemistry" §§) Actual half-cell potentials must be calculated by using the Nernst equation as the solutes are unlikely to be in their standard states:

The value of 2.303 R / F is 1.9845×10−4 V / K , so at T = 25 °C (298.15 K) the half-cell potential will change by only 0.05918 V/ νe if the concentration of a metal ion is increased or decreased by a factor of 10 .

When a current flows in the circuit, equilibrium conditions are not achieved and the cell voltage will usually be reduced by various mechanisms, such as the development of overpotentials.

Corrosion occurs when two dissimilar metals are in contact with each other in the presence of an electrolyte, such as salt water.

The resulting electrochemical potential then develops an electric current that electrolytically dissolves the less noble material.