Ganymede (mythology)

Homer describes Ganymede as the most handsome of mortals and tells the story of how he was abducted by the gods to serve as Zeus's cup-bearer in Olympus.

[a] Ganymede had been tending sheep, a rustic or humble pursuit characteristic of a hero's boyhood before his privileged status is revealed, when an eagle transported the youth to Mount Olympus.

[21] In Homer's account of the abduction in the Iliad, the poet writes: [Ganymedes] was the loveliest born of the race of mortals, and thereforethe gods caught him away to themselves, to be Zeus' wine-pourer,for the sake of his beauty, so he might be among the immortals.On Olympus, Zeus granted Ganymede eternal youth and immortality as the official cup bearer to the gods, in place of Hebe, who was relieved of cup-bearing duties upon her marriage to Herakles.

[28] In the Iliad, Zeus is said to have compensated Ganymede's father Tros with the gift of fine horses, "the same that carry the immortals", delivered by the messenger god Hermes.

[33] The Augustan poet Virgil portrays the abduction with pathos: the boy's aged tutors try in vain to draw him back to Earth, and his hounds bay uselessly at the sky.

[34] The loyal hounds left calling after their abducted master is a frequent motif in visual depictions and is referenced by Statius: Here the Phrygian hunter is borne aloft on tawny wings, Gargara’s range sinks downwards as he rises, and Troy grows dim beneath him; sadly stand his comrades; vainly the hounds weary their throats with barking, pursue his shadow or bay at the clouds.

[37] Leochares (c. 350 BCE), a Greek sculptor of Athens who was engaged with Scopas on the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus cast a lost bronze group of Ganymede and the Eagle, a work that was held remarkable for its ingenious composition.

Ganymede and Zeus in the guise of an eagle were a popular subject on Roman funerary monuments with at least 16 sarcophagi depicting this scene.

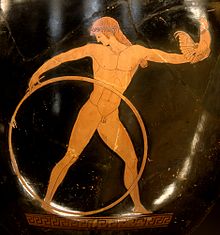

[41] Ganymede was a major symbol of homosexual love in the visual and literary arts from the Renaissance to the Late Victorian era, until when Antinous, the reported lover of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, became a more popular subject.

Ganymede also appears in the opening of Christopher Marlowe's play Dido, Queen of Carthage, where his and Zeus's affectionate banter is interrupted by an angry Aphrodite (Venus).

In El castigo sin venganza (1631) by Lope de Vega, Federico, the son of the Duke of Mantua, rescues Casandra, his future stepmother, and the pair will later develop an incestuous relationship.

To emphasize the non-normative relation, the work includes a long passage, possibly an ekphrasis derived from Italian art, in which Jupiter in the form of an eagle abducts Ganymede.

[46] One of the earliest surviving non-ancient depictions of Ganymede is a woodcut from the first edition of Emblemata (c. 1531), which shows the youth riding the eagle as opposed to being carried away.

Rubens painted two well-known versions, the earlier dating to 1611–1612 (Fürstlich Schwarzenbergische Kunststiftung, on permanent loan to the Liechtenstein Museum), portrays the young Ganymede in the embrace of the eagle being handed his cup,[48] while a later version dating to 1636–1638, painted for the Spanish king's hunting lodge (Museo del Prado), shows the young man being swept up violently by the eagle.