Garbhagriha

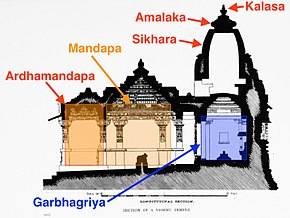

The typical Hindu and Jain garbhagriha is preceded by one or more adjoining pillared mandapas (porches or halls), which are connected to the sanctum by an open or closed vestibule (antarala),[5] and through which the priests or devotees may approach the holy shrine in order to worship the presence of the deity in profound, indrawn meditation.

[6] In addition to being square, the garbhagriha is most often windowless, has only one entrance that faces the eastern direction of the rising sun (though there are exceptions[7]), and is sparsely lit to allow the devotee's mind to focus on the tangible form of the divine within it.

An early prototype for this style of garbhagriha is the sixth century CE Deogarh temple in Uttar Pradesh State’s Jhansi district (which also has a small stunted shikhara over it).

[8] The style fully emerged in the eighth century CE and developed distinct regional variations in Orissa, central India, Rajasthan, and Gujarat.

[9] However, it should be remembered that throughout South Asia stone structures were always vastly outnumbered by buildings made of perishable materials, such as wood, bamboo, thatch and brick.

[10] Thus, while some early stone examples have survived, the earliest use of a square garbhagriha cannot be categorically dated simply because its original structural materials have long since decomposed.

There are a very few examples of larger variance: the chamber at Gudimallam is both semi-circular at the rear, and set below the main floor level of the temple (see bottom inset image).

Two cardinal axes, crossing at right angles, orient the ground plan: a longitudinal axis (running through the doorway, normally east-west) and a transverse one (normally north-south).

[19] The purpose of every Hindu temple is to be a house for a deity whose image or symbol is installed and whose presence is concentrated at the heart and focus of the building.

[24] This is consistent with other early Hindu images that often represented cosmic parturition—-the coming into present existence of a divine reality that otherwise remains without form-—as well as “meditational constructs".