Gardens of Versailles

On weekends from late spring to early autumn, the administration of the museum sponsors the Grandes Eaux – spectacles during which all the fountains in the gardens are in full play.

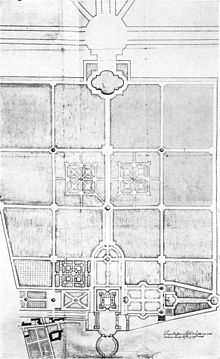

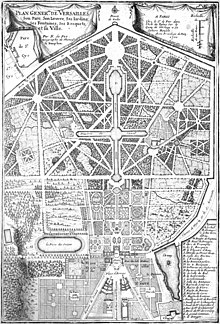

[4] With Louis XIII's final purchase of lands from Jean-François de Gondi in 1632 and his assumption of the seigneurial role of Versailles in the 1630s, formal gardens were laid out west of the château.

Records indicate that late in the decade Claude Mollet and Hilaire Masson designed the gardens, which remained relatively unchanged until the expansion ordered under Louis XIV in the 1660s.

[5] In 1661, after the disgrace of the finance minister Nicolas Fouquet, who was accused by rivals of embezzling crown funds in order to build his luxurious château at Vaux-le-Vicomte, Louis XIV turned his attention to Versailles.

As a result of this fête – particularly the lack of housing for guests (most of them had to sleep in their carriages), Louis realized the shortcomings of Versailles and began to expand the château and the gardens once again.

[14] Occupying the site of Rondeau/Bassin des Cygnes of Louis XIII, the Apollo Fountain, which was constructed between 1668 and 1671, depicts the sun god driving his chariot to light the sky.

(Berger I, 1985; Friedman, 1988,1993; Hedin, 1981–1982; Marie, 1968; Nolhac, 1901; Thompson, 2006; Verlet, 1961, 1985; Weber, 1981) One of the distinguishing features of the gardens during the second building campaign was the proliferation of bosquets.

(Marie 1972, 1975; Thompson 2006; Verlet 1985) Excavated in 1678, the Pièce d'eau des Suisses[34] – named for the Swiss Guards who constructed the lake – occupied an area of marshes and ponds, some of which had been used to supply water for the fountains in the garden.

[35] Modifications in the gardens during the third building campaign were distinguished by a stylistic change from the natural esthetic of André Le Nôtre to the architectonic style of Jules Hardouin Mansart.

In the same year, Le Vau's Orangerie, located to south of the Parterrre d'Eau was demolished to accommodate a larger structure designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart.

(Marie 1976; Thompson 2006; Verlet 1985) With the departure of the king and court from Versailles in 1715 following the death of Louis XIV, the palace and gardens entered an era of uncertainty.

In the area now occupied by the Hameau de la Reine, Louis XV constructed and maintained les jardins botaniques – the botanical gardens.

(Thompson 2006; Verlet 1985) At the Petit Trianon, which was gifted to Marie Antoinette by Louis XVI in 1774, the new Queen dramatically relandscaped the surrounding parkland and gardens.

[44] A lake and several meandering rivers were formed as part of the new landscaping and the architect Richard Mique was entrusted with designing follies to embellish the gardens like the Grotto, the Belvedere and the Temple of Love.

These plans were never put into action; however, the gardens were opened to the public – it was not uncommon to see people washing their laundry in the fountains and spreading it on the shrubbery to dry..[16] In 1793 most of the decorative pieces of the Triumphal Arch Grove were destroyed.

In 1817, Louis XVIII ordered the conversion of the Île du Roi and the Miroir d'Eau into an English-style garden – the Jardin du Roi..[16] While much of the château's interior was irreparably altered to accommodate the Museum of the History of France dedicated to "all the glories of France" (inaugurated by Louis Philippe I on 10 June 1837), the gardens, by contrast, remained untouched.

Nolhac, an ardent archivist and scholar, began to piece together the history of Versailles, and subsequently established the criteria for restoration of the château and preservation of the gardens, which are ongoing to this day.

Located north and south of the east–west axis, these two bosquets were arranged as a series of paths around four salles de verdure and which converged on a central "room" that contained a fountain.

Originally designed by André Le Nôtre in 1661 as a salle de verdure, this bosquet contained a path encircling a central pentagonal area.

Originally designed in 1671 as two separate water features, the larger – Île du Roi – contained an island that formed the focal point of a system of elaborate fountains.

The central feature of this bosquet, which was designed by Le Nôtre between 1671 and 1674, was an auditorium/theater sided by three tiers of turf seating that faced a stage decorated with four fountains alternating with three radiating cascades.

Designed as a simple unadorned salle de verdure by Le Nôtre in 1678, the landscape architect enhanced and incorporated an existing stream to create a bosquet that featured rivulets that twisted among nine islets.

The galerie was completely remodeled in 1704 when the statues were transferred to Marly and the bosquet was replanted with horse chestnut trees (Aesculus hippocastanum) – hence the current name Salle des Marronniers (Marie 1968, 1972, 1976, 1984; Thompson 2006; Verlet 1985).

Located west of the Parterre du Midi and south of the Latona Fountain, this bosquet, which was designed by Le Nôtre and built between 1681 and 1683, features a semi-circular cascade that forms the backdrop for this salle de verdure.

Interspersed with gilt lead torchères, which supported candelabra for illumination, the Salle de Bal was inaugurated in 1683 by Louis XIV's son, the Grand Dauphin, with a dance party.

This was achieved in the Parterre de Latone in 2013, when the 19th century lawns and flower beds were replaced with boxwood-enclosed turf and gravel paths to create a formal arabesque design.

[16] With the completion of the Grand Canal in 1671, which served as drainage for the fountains of the garden, water, via a system of windmills, was pumped back to the reservoir on top of the Grotte de Thétys.

Seizing upon the success of a system devised in 1680 that raised water from the Seine to the gardens of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, construction of the Machine de Marly began the following year.

However, owing to leakage in the conduits and breakdowns of the mechanism, the machine was only able to deliver 3,200 m3 (110,000 cu ft) of water per day – approximately one-half the expected output.

In this year it was proposed to divert the water of the Eure river, located 160 km (99 mi) south of Versailles and at a level 26 m (85 ft) above the garden reservoirs.