Gargantua and Pantagruel

[6] In a social climate of increasing religious oppression in the lead up to the French Wars of Religion, contemporaries treated it with suspicion and avoided mentioning it.

The original title of the work was Pantagruel roy des dipsodes restitué à son naturel avec ses faictz et prouesses espoventables.

On receiving a letter with news that his father has been translated to Fairyland by Morgan le Fay, and that the Dipsodes, hearing of it, have invaded his land and are besieging a city, Pantagruel and his companions depart.

Through subterfuge, might, and urine, the besieged city is relieved, and their residents are invited to invade the Dipsodes, who mostly surrender to Pantagruel as he and his army approach their towns.

Again, they continue their voyage, passing, or landing at, places of interest, until the book ends, with the ships firing a salute, and Panurge soiling himself.

Passing by the abbey of the sexually prolific Semiquavers, and the Elephants and monstrous Hearsay of Satin Island, they come to the realms of darkness.

After drinking liquid text from a book of interpretation, Panurge concludes wine inspires him to right action, and he forthwith vows to marry as quickly and as often as possible.

[10] M. A. Screech is of this latter opinion, and, introducing his translation, he bemoans that "[s]ome read back into the Four books the often cryptic meanings they find in the Fifth".

J. M. Cohen, in his Introduction to a Penguin Classics edition, indicates that chapters 17–48 were so out-of-character as to be seemingly written by another person, with the Fifth Book "clumsily patched together by an unskilful editor.

"[14] Mikhail Bakhtin's book Rabelais and His World (published in 1965) explores Gargantua and Pantagruel and is considered a classic of Renaissance studies.

Here, in the town square, a special form of free and familiar contact reigned among people who were usually divided by the barriers of caste, property, profession, and age".

The grotesque is the term used by Bakhtin to describe the emphasis of bodily changes through eating, evacuation, and sex: Rabelais uses it as a measuring device.

Sileni, as Rabelais informs the reader, were little boxes "painted on the outside with merry frivolous pictures"[20] but used to store items of high value.

[21] In these opening pages of Gargantua, Rabelais exhorts the reader "to disregard the ludicrous surface and seek out the hidden wisdom of his book";[21] but immediately "mocks those who would extract allegorical meanings from the works of Homer and Ovid".

[21] Rabelais has "frequently been named as the world's greatest comic genius";[22] and Gargantua and Pantagruel covers "the entire satirical spectrum".

[23] Its "combination of diverse satirical traditions"[23] challenges "the readers' capacity for critical independent thinking";[23] which latter, according to Bernd Renner, is "the main concern".

According to John Parkin, the "humorous agendas are basically four":[22] In the wake of Rabelais' book the word gargantuan (glutton) emerged, which in Hebrew is גרגרן Gargrån.

[25] In intellectual circles, at the time, to quote or name Rabelais was "to signal an urban(e) wit, [and] good education";[25] though others, particularly Puritans, cited him with "dislike or contempt".

[25] Rabelais' fame and influence increased after Urquhart's translation; later, there were many perceptive imitators, including Jonathan Swift (Gulliver's Travels) and Laurence Sterne (Tristram Shandy).

[27] The work was first translated into English by Thomas Urquhart (the first three books) and Peter Anthony Motteux (the fourth and fifth) in the late seventeenth-century.

From The Third Book, Chapter Seven: Copsbody, this is not the Carpet whereon my Treasurer shall be allowed to play false in his Accompts with me, by setting down an X for an V, or an L for an S; for in that case, should I make a hail of Fisti-cuffs to fly into his face.

[30]William Francis Smith (1842–1919) made a translation in 1893, trying to match Rabelais' sentence forms exactly, which renders the English obscure in places.

[29] Also well annotated is an abridged but vivid translation of 1946 by Samuel Putnam, which appears in a Viking Portable edition that was still in print as late as 1968.

Donald M. Frame, with his own translation, calls Putnam's edition "arguably the best we have";[c] but notes that "English versions of Rabelais [...] all have serious weaknesses".

[29] John Michael Cohen's modern translation, first published in 1955 by Penguin, "admirably preserves the frankness and vitality of the original", according to its back cover, although it provides limited explanation of Rabelais' word-plays and allusions.

"[31] Frame's edition, according to Terence Cave, "is to be recommended not only because it contains the complete works but also because the translator was an internationally renowned specialist in French Renaissance studies".

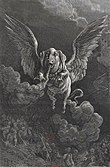

[36]Andrew Brown (2003; revised 2018); books 1 and 2 only The most famous and reproduced illustrations for Gargantua and Pantagruel were done by French artist Gustave Doré and published in 1854.