Lucian

Lucian of Samosata[a] (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, c. 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridiculed superstition, religious practices, and belief in the paranormal.

According to his oration The Dream, he was the son of a lower middle class family from the city of Samosata along the banks of the Euphrates in the remote Roman province of Syria.

Lucian's works were wildly popular in antiquity, and more than eighty writings attributed to him have survived to the present day, a considerably higher quantity than for most other classical writers.

Philosophies for Sale and The Carousal, or The Lapiths make fun of various philosophical schools, and The Fisherman or the Dead Come to Life is a defense of this mockery.

[2] Daniel S. Richter criticizes the frequent tendency to interpret such "Lucian-like figures" as self-inserts by the author[2] and argues that they are, in fact, merely fictional characters Lucian uses to "think with" when satirizing conventional distinctions between Greeks and Syrians.

[2] He suggests that they are primarily a literary trope used by Lucian to deflect accusations that he as the Syrian author "has somehow outraged the purity of Greek idiom or genre" through his invention of the comic dialogue.

[5] British classicist Donald Russell states, "A good deal of what Lucian says about himself is no more to be trusted than the voyage to the moon that he recounts so persuasively in the first person in True Stories"[6] and warns that "it is foolish to treat [the information he gives about himself in his writings] as autobiography.

[14][15] Most educated people of Lucian's time adhered to one of the various Hellenistic philosophies,[14] of which the major ones were Stoicism, Platonism, Peripateticism, Pyrrhonism, and Epicureanism.

[17] Richter argues that it is not autobiographical at all, but rather a prolalia (προλᾰλιά), or playful literary work, and a "complicated meditation on a young man's acquisition of paideia" [i.e.

[19] Russell dismisses The Dream as entirely fictional, noting, "We recall that Socrates too started as sculptor, and Ovid's vision of Elegy and Tragedy (Amores 3.1) is all too similar to Lucian's.

[7][11] Lucian mentions in his dialogue The Fisherman that he had initially attempted to apply his knowledge of rhetoric and become a lawyer,[23] but that he had become disillusioned by the deceitfulness of the trade and resolved to become a philosopher instead.

[28] Later, in the same dialogue, he praises a book written by Epicurus: What blessings that book creates for its readers and what peace, tranquillity, and freedom it engenders in them, liberating them as it does from terrors and apparitions and portents, from vain hopes and extravagant cravings, developing in them intelligence and truth, and truly purifying their understanding, not with torches and squills [i. e. sea onions] and that sort of foolery, but with straight thinking, truthfulness and frankness.

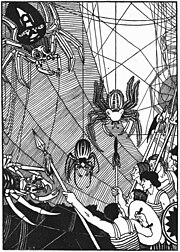

[61][62] Blown off course by a storm, they come to an island with a river of wine filled with fish and bears, a marker indicating that Heracles and Dionysus have traveled to this point, and trees that look like women.

[86] The dialogue draws on earlier literary precursors, including the nekyia in Book XI of Homer's Odyssey,[87] but also adds new elements not found in them.

[91] When Tychiades objects that such remedies do not work, the others all laugh at him[91] and try to persuade him to believe in the supernatural by telling him stories, which grow increasingly ridiculous as the conversation progresses.

[41] In The Fisherman, or the Dead Come to Life, Lucian defends his other dialogues by comparing the venerable philosophers of ancient times with their unworthy contemporary followers.

[95] In Icaromenippus [fi], the Cynic philosopher Menippus fashions a set of wings for himself in imitation of the mythical Icarus and flies to Heaven,[96] where he receives a guided tour from Zeus himself.

[97] The dialogue ends with Zeus announcing his decision to destroy all philosophers, since all they do is bicker, though he agrees to grant them a temporary reprieve until spring.

[41] Throughout all his dialogues, Lucian displays a particular fascination with Hermes, the messenger of the gods,[89] who frequently appears as a major character in the role of an intermediary who travels between worlds.

[114] In it, he describes dance as an act of mimesis ("imitation")[115] and rationalizes the myth of Proteus as being nothing more than an account of a highly skilled Egyptian dancer.

[41] In his treatise, How to Write History, Lucian criticizes the historical methodology used by writers such as Herodotus and Ctesias,[116] who wrote vivid and self-indulgent descriptions of events they had never actually seen.

[118] In the letter, one of Lucian's characters delivers a speech ridiculing Christians for their perceived credulity and ignorance,[119] but he also affords them some level of respect on account of their morality.

[119] In the letter Against the Ignorant Book Collector, Lucian ridicules the common practice whereby Near Easterners collect massive libraries of Greek texts for the sake of appearing "cultured", but without actually reading any of them.

[140][141][139] Many early modern European writers adopted Lucian's lighthearted tone, his technique of relating a fantastic voyage through a familiar dialogue, and his trick of constructing proper names with deliberately humorous etymological meanings.

[29] Perhaps the most notable example of Lucian's impact in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was on the French writer François Rabelais, particularly in his set of five novels, Gargantua and Pantagruel, which was first published in 1532.

Menippos: And for this a thousand ships carried warriors from every part of Greece, Greeks and barbarians were slain, and cities made desolate?Francis Bacon called Lucian a "contemplative atheist".

[150] Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux, François Fénelon, Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, and Voltaire all wrote adaptations of Lucian's Dialogues of the Dead.

Thomas Carlyle's epithet "Phallus-Worship", which he used to describe the contemporary literature of French writers such as Honoré de Balzac and George Sand, was inspired by his reading of Lucian.

echoes the exact wording of Tiresias's final advice to the eponymous hero of Lucian's dialogue Menippus: "Laugh a great deal and take nothing seriously.

"[151] Professional philosophical writers since then have generally ignored Lucian,[29] but Turner comments that "perhaps his spirit is still alive in those who, like Bertrand Russell, are prepared to flavor philosophy with wit.