Compressible flow

The study of gas dynamics is often associated with the flight of modern high-speed aircraft and atmospheric reentry of space-exploration vehicles; however, its origins lie with simpler machines.

At the beginning of the 19th century, investigation into the behaviour of fired bullets led to improvement in the accuracy and capabilities of guns and artillery.

[2] As the century progressed, inventors such as Gustaf de Laval advanced the field, while researchers such as Ernst Mach sought to understand the physical phenomena involved through experimentation.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the focus of gas dynamics research shifted to what would eventually become the aerospace industry.

[2] Theodore von Kármán, a student of Prandtl, continued to improve the understanding of supersonic flow.

Other notable figures (Meyer, Luigi Crocco [it], and Ascher Shapiro) also contributed significantly to the principles considered fundamental to the study of modern gas dynamics.

Amongst other factors, conventional aerofoils saw a dramatic increase in drag coefficient when the flow approached the speed of sound.

Much of basic gas dynamics is analytical, but in the modern era Computational fluid dynamics applies computing power to solve the otherwise-intractable nonlinear partial differential equations of compressible flow for specific geometries and flow characteristics.

Instead, the continuum assumption allows us to consider a flowing gas as a continuous substance except at low densities.

Most problems in incompressible flow involve only two unknowns: pressure and velocity, which are typically found by solving the two equations that describe conservation of mass and of linear momentum, with the fluid density presumed constant.

Otherwise, more complex equations of state must be considered and the so-called non ideal compressible fluids dynamics (NICFD) establishes.

Fluid dynamics problems have two overall types of references frames, called Lagrangian and Eulerian (see Joseph-Louis Lagrange and Leonhard Euler).

The Eulerian frame is most useful in a majority of compressible flow problems, but requires that the equations of motion be written in a compatible format.

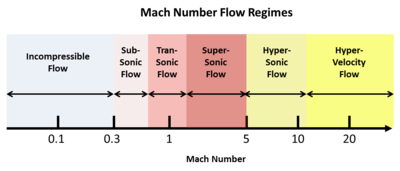

Above about Mach 5, these wave angles grow so small that a different mathematical approach is required, defining the hypersonic speed regime.

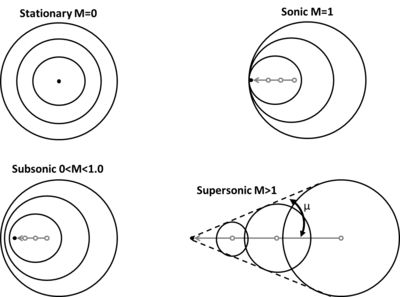

As an object accelerates from subsonic toward supersonic speed in a gas, different types of wave phenomena occur.

To illustrate these changes, the next figure shows a stationary point (M = 0) that emits symmetric sound waves.

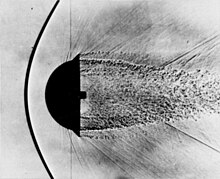

Upon achieving supersonic flow, the particle is moving so fast that it continuously leaves its sound waves behind.

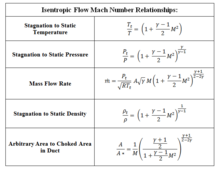

Using the conservation laws of fluid dynamics and thermodynamics, the following relationship for channel flow is developed (combined mass and momentum conservation): where dP is the differential change in pressure, M is the Mach number, ρ is the density of the gas, V is the velocity of the flow, A is the area of the duct, and dA is the change in area of the duct.

Therefore, to accelerate a flow to Mach 1, a nozzle must be designed to converge to a minimum cross-sectional area and then expand.

If the speed of the flow is to continue to increase, its density must decrease in order to obey conservation of mass.

As previously mentioned, in order for a flow to become supersonic, it must pass through a duct with a minimum area, or sonic throat.

When analysing a normal shock wave, one-dimensional, steady, and adiabatic flow of a perfect gas is assumed.

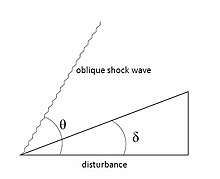

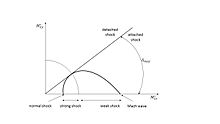

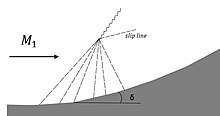

Based on the level of flow deflection (δ), oblique shocks are characterized as either strong or weak.

An irregular reflection is much like the case described above, with the caveat that δ is larger than the maximum allowable turning angle.

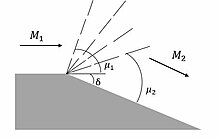

It is possible to accelerate supersonic flow in what has been termed a Prandtl–Meyer expansion fan, after Ludwig Prandtl and Theodore Meyer.

Flow can expand around either a sharp or rounded corner equally, as the increase in Mach number is proportional to only the convex angle of the passage (δ).

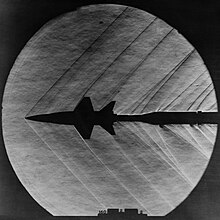

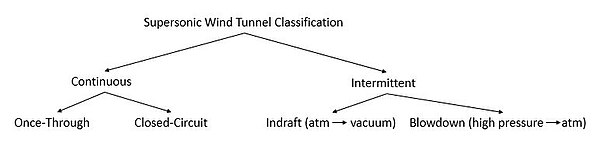

The operating principle behind the wind tunnel is that a large pressure difference is maintained upstream to downstream, driving the flow.

Continuous operating supersonic wind tunnels require an independent electrical power source that drastically increases with the size of the test section.

Blowdown type supersonic wind tunnels offer high Reynolds number, a small storage tank, and readily available dry air.

One purpose of the inlet is to minimize losses across the shocks as the incoming supersonic air slows down to subsonic before it enters the turbojet engine.