Three-spined stickleback

Many populations are anadromous (they live in seawater but breed in fresh or brackish water) and very tolerant of changes in salinity, a subject of interest to physiologists.

The oldest record of the species is from the Alta Mira Shale of the Monterey Formation of California, which preserves an articulated skeleton that appears essentially identical to the modern G. aculeatus complex.

[5][6] The iconic evolutionary traits of the three-spined stickleback, including rapid evolution in isolated environments, reduction of armor & pelvis, and ecological divisions into different niches, appear to have been a longstanding tendency of the Gasterosteus lineage.

These traits are all present in a fossil stickleback, Gasterosteus doryssus, known from Miocene-aged freshwater deposits of the Truckee Formation in Nevada, US, which saw rapid evolution and morphological change over a period of several thousand years.

In males during the breeding season, the eyes become blue and the lower head, throat, and anterior belly turn bright red.

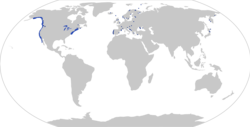

[9] The three-spined stickleback is found only in the Northern Hemisphere, where it usually inhabits coastal waters or freshwater bodies.

It can be found in ditches, ponds, lakes, backwaters, quiet rivers, sheltered bays, marshes, and harbours.

In North America, it ranges along the East Coast from Chesapeake Bay to the southern half of Baffin Island and the western shore of Hudson Bay, and along the West Coast from southern California to the western shore of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands.

These populations were probably formed when anadromous fish started spending their entire lifecycle in fresh water, and thus evolved to live there all year round.

Freshwater populations are extremely morphologically diverse, to the extent that many observers (and some taxonomists) would describe a new subspecies of three-spined stickleback in almost every lake in the Northern Hemisphere.

The fish in the deep lakes typically feed in the surface waters on plankton, and often have large eyes, with short, slim bodies and upturned jaws.

Populations have been observed rapidly adapting to different conditions, such as in Lake Union, where sticklebacks have lost and regained armor plates in response to pollution from human activity around the watershed.

The evolutionary dynamics of these species pairs are providing a model for the processes of speciation which has taken place in less than 20 years in at least one lake.

In 1982, a chemical eradication program intended to make room for trout and salmon at Loberg Lake, Alaska, killed the resident freshwater populations of sticklebacks.

Although sticklebacks are found in many locations around the coasts of the Northern Hemisphere and are thus viewed by the IUCN as species of least concern, the unique evolutionary history encapsulated in many freshwater populations indicates further legal protection may be warranted.

[1] In its different forms or stages of life, the three-spined stickleback can be a bottom-feeder (most commonly chironomid larvae and amphipods)[18] or a planktonic feeder in lakes or in the ocean; it can also consume terrestrial prey fallen to the surface.

He then fills it with plant material (often filamentous algae), sand, and various debris which he glues together with spiggin, a proteinaceous substance secreted from the kidneys.

[citation needed] The sequence of territorial courtship and mating behaviours was described in detail by Niko Tinbergen in a landmark early study in ethology.

[25][26][27][28] However, the response to red is not universal across the entire species,[29][30] with black throated populations often found in peat-stained waters.

Once the young hatch, the male attempts to keep them together for a few days, sucking up any wanderers into his mouth and spitting them back into the nest.

Two sticklebacks simultaneously presented to a rainbow trout, a predator much larger in size, will have differing risks of being attacked.

The three-spined stickleback is a secondary intermediate host for the hermaphroditic parasite Schistocephalus solidus, a tapeworm of fish and fish-eating birds.

Three-spined sticklebacks have recently become a major research organism for evolutionary biologists trying to understand the genetic changes involved in adapting to new environments.

The entire genome of a female fish from Bear Paw Lake in Alaska was recently sequenced by the Broad Institute and many other genetic resources are available.

[54][56][57] Three-spined stickleback are particularly useful for studying eco-evolutionary dynamics because multiple populations have evolved rapidly and in predictable, repeated patterns after colonizing new environments.

[52][53] Most eco-evolutionary dynamics research in sticklebacks has focused on how the adaptive radiation of different ecotypes affects ecological processes.

[59] The impacts of ecotype specialization on prey communities can even affect the abundance of algae and cyanobacteria that do not directly interact with sticklebacks, along with aspects of the abiotic environment,[59][60] such as the amount of ambient light available for photosynthesis[59] and levels of dissolved oxygen,[59] carbon,[61] and phosphorus.

[64][65][66] Three-spined sticklebacks can be hosts to a variety of parasites (e.g., Schistocephalus solidus, a common tapeworm of fish and fish-eating birds[45]).

[64] These ecosystem impacts can further affect selection on sticklebacks in subsequent generations, which suggests a complex feedback loop between the evolution of host-parasite interactions, community composition, and abiotic conditions.

[64] Many researchers have used mesocosm experiments to test how the adaptive radiation of stickleback ecotypes and stickleback-parasite interactions can impact ecological processes.